Towering high above the sunbaked rolling plains and olive groves of central Greece, Mount Parnassus looks down sternly on its surroundings. It is a forbidding world of craggy limestone structures and steep cliffs, and on its slope, we find the village of Delphi, home to the famed oracle from ancient Greek history. Mount Parnassus is actually a series of summits, but the two highest elevations are frequently shrouded in clouds. In Classical times, the mountain was considered sacred, and the two highest peaks were called Tithorea and Lycoreia. One of the peaks was sacred to Apollo and the nine Muses, while the other was sacred to Dionysus. According to mythology, Orpheus was also living on Parnassus with his mother and eight beautiful aunts. He met the god Apollo, courting the laughing muse Thalia. Apollo gave Orpheus a golden lute, and his mother taught him to make verses for singing. And thus the first musical superstar came into existence. Since Parnassus, and the famed fountain Castalia, was home of the Muses, the mountain became known as the home of poetry, music, and learning. In more recent times, that fabled mountain has inspired a number of poetic-artistic trends, and it has lent its name to various books of instruction and guides.

Mount Parnassus

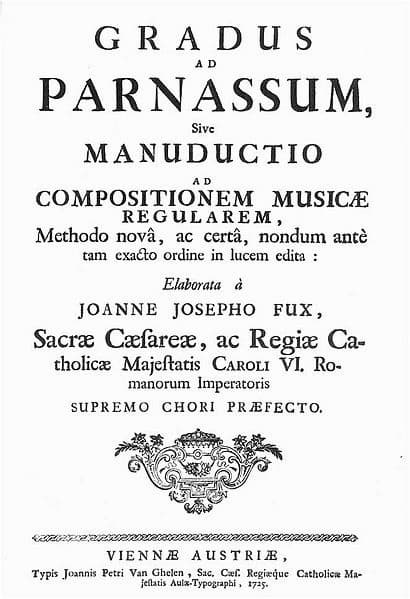

The Latin phrase “Gradus ad Parnassum,” basically means “steps to Parnassus.” It denotes a gradual progress of instruction in literature, language and music. The composer Johann Joseph Fux (1660-1741) wrote one of the most famous theoretical and pedagogical works titled “Gradus ad Parnassum” in 1725.

Johann Joseph Fux: Concentus musico-instrumentalis, Sinfonio No. 2 (Concentus Musicus Wien; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

Johann Joseph Fux: Gradus ad Parnassum

This highly important textbook on counterpoint is divided into two major parts. The first looks at music from a purely mathematical angle in a tradition that goes all the way back to the Ancient Greeks. The practical part presents instruction on counterpoint, fugue, double counterpoint and an essay on musical taste. Most subsequent books on counterpoint take Fux’s treatise as their starting point, and the work was admired and exerted great influence on Johann Sebastian Bach. We also know that Leopold Mozart used the Fux “Gradus” to teach his son Wolfgang, and Beethoven had nothing but praise for Fux and his treatise. And we also know that Joseph Haydn meticulously worked through all the exercises. Roughly 100 years later, Muzio Clementi completed his three-volume “Gradus ad Parnassum.” It represents “the culmination of Clementi’s career, exhibiting a veritable treasury of compositional and pianistic technique compiled from all periods of his work. From pure finger drills to preludes, fugues, canons, and sonata movements, the one hundred exercises constitute a stylistically diverse array of studies covering all aspects of piano playing.”

Muzio Clementi: Gradus ad Parnassum, Op. 44 (Michele Campanella, piano; Sandro De Palma, piano; Maria Mosca, piano; Vincenzo Vitale, piano; Aldo Tramma, piano; Carlo Bruno, piano; Laura de Fusco, piano; Franco Medori, piano)

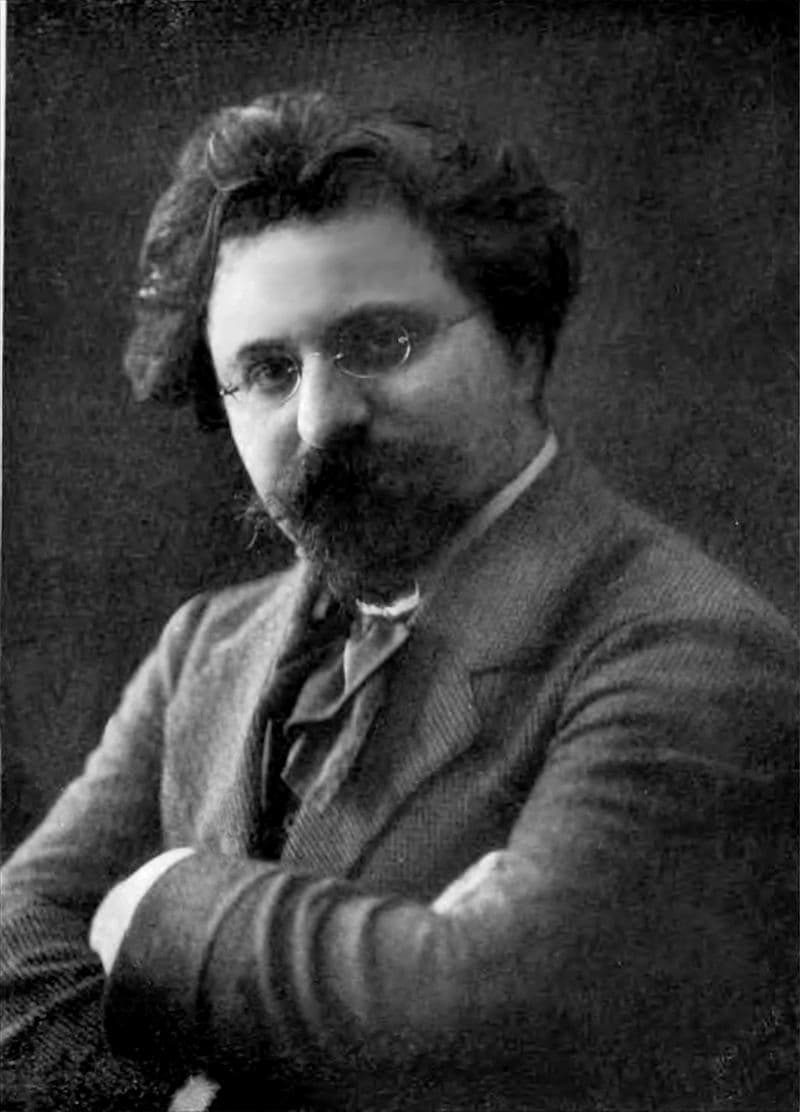

Like Fux’s treatise, Clementi’s monumental work was designed to ascend to the highest level of musical and technical perfection. The German composer and keyboardist Sigfried Karg-Elert (1877-1933) is primarily known for his harmonium and organ works. Initially, he composed under the influence of Schoenberg, Scriabin, and Debussy, but eventually, he broke away from these influences. In 1919 Karg-Elert was appointed to succeed Max Reger at the Leipzig Conservatory, teaching composition and theory. He would hold this post for the rest of his life, and his musical compositions have been regarded “as a quest for completely individual language.” Karg-Elert maintained a link to the musical language of Late Romanticism, with the frequent use of chromaticism, rich decorations, capricious groupings and adventurous chromatic key relations, sometimes in very quick succession. The 30 Caprices, a “Gradus ad Parnassum of Modern Technique for the Solo Flute” dates from 1918/19 and employs Classical, Romantic and Baroque forms. The composer wrote, “The Caprices have their origin in the Classical technique of Bach, Handel and Mozart and quickly ignore contemporary dictates. In each of the Caprices, a different musical idea is pivotal and is worked through with extreme precision to achieve a polished whole.”

Sigfrid Karg-Elert, 1913

Sigfrid Karg-Elert: 30 Capricien, Op. 107, “Gradus ad Parnassum” (Thies Roorda, flute)

For American composer Philipp Glass, music is and has always been a process. Glass traveled to Paris in the mid-1960s to study with Nadia Boulanger and the Indian Sitar master Ravi Shankar. These studies had a significant impact on his approach to rhythm and strongly influenced his music. The composer writes, “Although the melodic aspect of Indian Music is fascinating, it is not what attracted my attention then, and not what has held it ever since. What came to me as a revelation was the use of rhythm in developing an overall structure in music. I would describe the difference between the use of rhythm in Western and Indian music in the following way: in Western music, we divide time – as if you were to take a length of time and slice it the way you slice a loaf of bread. In Indian music (and all the non- Western music with which I am familiar), you take small units, or ‘beats’, and string them together to make up larger time values.” Such is the case in his “Gradus,” originally written for soprano saxophone. The work juxtaposes melodic and rhythmic material within a repeated cycle of 32 beats. “Although highly structured, it sounds highly intuitive and unpredictable.”

Philip Glass: Gradus (arr. C. Morris) (Craig Morris, trumpet)

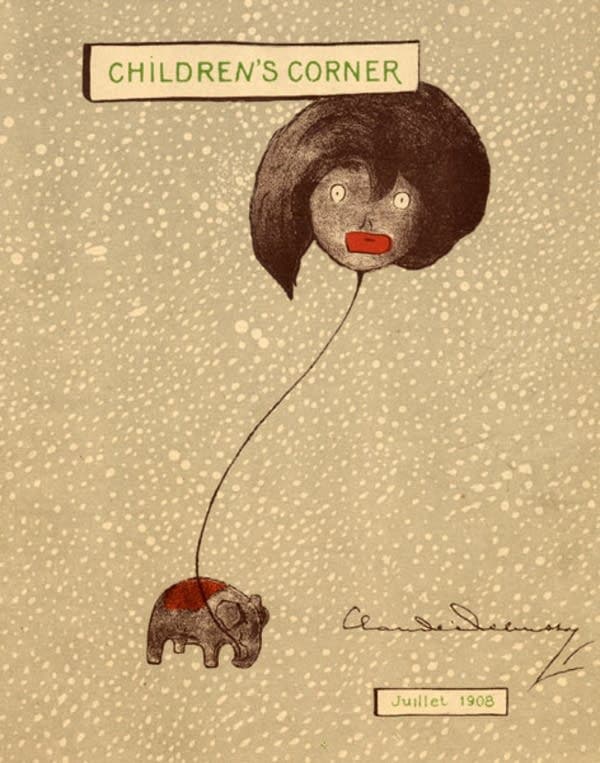

Claude Debussy’s Children’s Corner

Let us conclude this little Parnassus survey with a much-loved composition by Claude Debussy (1862-1918). He dedicated a suite for solo piano to his daughter Claude-Emma—affectionately known as “Chou-Chou” in 1908. Children’s Corner, as the collection was known, comprises a series of six piano miniatures. The composer wrote, “To my beloved Chouchou, with the tender excuses of her father for that which follows.” Here, we find “Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum,” a play on words making reference to Clementi’s piano method. It is a satirical take on finger exercises, and according to Debussy, “this is a kind of hygienic and advanced gymnastics; therefore, it is recommended to play this piece every morning on an empty stomach, beginning moderato, ending lively…” I can assure you from personal experience, however, that you wouldn’t want to climb Mount Parnassus on an empty stomach.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter