Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) and his sister Fanny were born into a prosperous and prominent Jewish family. Extraordinarily talented, they grew up in a highly intellectual environment. Visitors to the salon organized by their parents included the poets Heinrich Heine and Karl von Holtei, Ludwig Börne, the philosopher Hegel, the classicist August Böckh, and the scientist Alexander von Humboldt. It has been said that “Europe came to their living room.” It’s no surprise that young Mendelssohn quickly made friends with a substantial number of high-profile personalities and musicians, including the violinist Eduard Rietz (1802-1832).

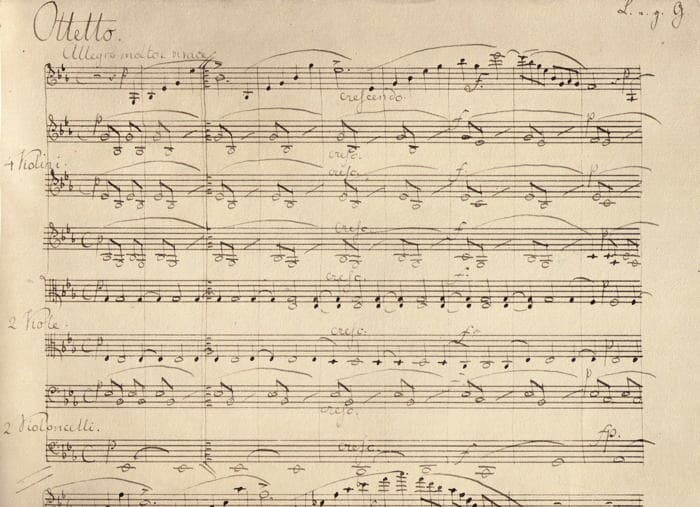

Mendelssohn’s Octet autograph

Mendelssohn counted him among his dearest and nearest friends, and his earliest letters teem with affectionate references to him. In addition, Mendelssohn had the highest possible opinion of Rietz’s power as a performer. He writes, “I long earnestly for his violin and his depth of feeling; they come vividly before my mind when I see his beloved neat handwriting.” Mendelssohn composed his first indisputable masterpiece, the Octet Op. 20 for Rietz, whose influence is heard in the florid first violin part. Rietz was only slightly older than Mendelssohn, and the untimely death of his violin friend affected him deeply. He wrote to the family, “…it is but yesterday that I heard of my irreparable loss… I never again can feel happy. I must now set about forming new plans, and building fresh castles in the air; the former ones are irrevocably gone, for he was interwoven with them all.”

Felix Mendelssohn: Octet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 (Vienna Octet)

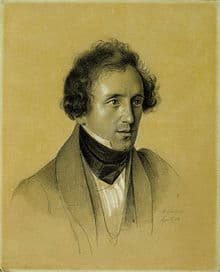

Carl Klingemann

Aside from members of his family, Felix Mendelssohn’s closest lifelong friend was Carl Klingemann (1798–1862). Eleven years older than Mendelssohn, Klingemann had a great sense of humor and great literary and musical interests. For a while, he even rented an apartment in the Mendelssohn house. Klingemann was employed in the diplomatic services of the King of Hanover, and in 1827 he was posted to London. In all, Mendelssohn made ten visits to Britain, and Klingemann offered him lodgings and the two friends even embarked on their famous tour to Scotland. They corresponded regularly, and agreed on a monthly exchange of correspondence, with Mendelssohn writing at the beginning, and Klingemann in the middle of the month. As a result, 157 letters from Mendelssohn and 154 from Klingemann survive, and their friendship was a highly private affair. In March of 1841, the Viennese publisher Pietro Mechetti invited Mendelssohn to submit a piano work for a collection to be published in support of a Beethoven monument being built in Bonn. Felix reported enthusiastically to Klingemann. “Do you know what I have just been composing passionately? Variations for Piano. I started right off with a theme in D minor, and I had such a heavenly time doing it that I went right on with new variations on a theme in E-flat… It seems as though I had to make up for never having written any before.”

Felix Mendelssohn: Variations sérieuses (Constance Keene, piano)

Julius Schubring

There is much scholarly debate as to whether Felix Mendelssohn defined himself as Jewish. Clearly, he was a sincere Lutheran and a proud German, but how important was Mendelssohn’s Jewish heritage to his self-understanding and to his religious worldview? The oratorio St. Paul was commissioned in 1832, and the libretto recounts the conversion of Saul of Tarsus—who violently persecuted the followers of Jesus—into St. Paul, one of the most influential apologists of the Christian faith. The most popular work during Mendelssohn’s lifetime, the composer spent almost four years writing and redrafting the libretto in consultation with the theologian and childhood friend Pastor Julius Schubring (1806-1889). Their extensive correspondence details discussions on all matters of theology, and the result was “a utopian Protestant project rooted in the Judaism of his grandfather that was centered on enlightenment, harmony and the transcendence of nationalism and religious difference. Mendelssohn spoke to his fellow humans through music on the assumption that rational ethics could govern human behavior…” Unsurprisingly, Mendelssohn would once again enlist Schubring’s help for the libretto of his oratorio Elijah.

Felix Mendelssohn: St. Paul, Part 2 (Sabine Goetz, soprano; Dorothèe Zimmermann, alto; Markus Brutscher, tenor; Klaus Mertens, bass; Schlosskirche Weilburg Kantorei; Capella Weilburgensis; Doris Hagel, cond.)

Delphine von Schauroth

In 1816 and 1817 the Mendelssohn family visited Paris. The children took piano lessons with Marie Bigot, whose technique had been admired by Haydn and Beethoven, and they played chamber music with the violinist Pierre Baillot. Felix returned to Paris in 1825 and participated in the virtuoso circuit, sending home critical letters about French musical life. “The 14-year-old Liszt,” he writes, “has many fingers but not much intelligence, Reicha is chasing parallel 5ths and Cherubini is an extinct volcano that occasionally spewed forth ash.” He also met the seven-year-old Delphine von Schauroth who took piano lessons from Friedrich Kalkbrenner. He met her again in 1830 and described her as “an artist, and very cultured, whom everyone adores.” As it happens, Mendelssohn fell deeply in love and formally asked for permission to marry her. The happy union did not materialize, but Mendelssohn did write and dedicated his Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25 under Delphine’s spell.

Felix Mendelssohn: Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 25 (Rudolf Firkušný, piano; Luxembourg Radio Orchestra; Louis de Froment, cond.)

Friedrich Wilhelm von Schadow:

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, 1834

In November 1821, Felix Mendelssohn and his composition teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter traveled to Weimar to visit Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). During the two-week stay, Mendelssohn played rhyme games with Goethe’s daughter-in-law and enjoyed daily conversations with Germany’s greatest living poet. In addition, Mendelssohn was called upon to perform for Goethe and for members of the Weimar ducal court, including Kapellmeister Hummel. Mendelssohn played several Bach fugues, the overture to Mozart’s Nozze di Figaro, sight-read autographs by Mozart and Beethoven, and played his own compositions and improvisations. Goethe subsequently had a private conversation with Zelter, “Musical prodigies… are probably no longer so rare; but what this little man can do in extemporizing and playing at sight borders the miraculous, and I could not have believed it possible at so early an age.” Zelter asked, “And yet you heard Mozart in his seventh year at Frankfurt?” “Yes,” answered Goethe, “… but what your pupil already accomplishes, bears the same relation to the Mozart of that time that the cultivated talk of a grown-up person bears to the prattle of a child.” Mendelssohn visited Goethe on several occasions, and he did set a number of Goethe’s poems to music.

Felix Mendelssohn: Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Op. 27 (London Symphony Orchestra; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.)

Adolf Bernhard Marx

Among Mendelssohn’s friends was the noted music critic and theorist Adolf Bernhard Marx (1795-1866). As editor of the Berliner Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, Marx contributed several articles about Beethoven, programmatic music, and aesthetics. “When I first saw him,” Marx writes, Mendelssohn stood at the brink between boyhood and youth. Through his masterful performances and compositions, he had already made a name for himself that reverberated far beyond the city… Several times one acquaintance or another had offered to introduce me to the household during the regular Sunday musical performances. Finally, it came about… Now there I was at one of those Sunday concerts, for which Felix had written a series of symphonies in three or four movements, the first movement a fugue, or fugato, the whole for stringed instruments alone.” On Mendelssohn’s recommendation, Marx was appointed professor of music at the University of Berlin in 1830, but only a couple of years later the two friends were estranged. Apparently, Mendelssohn prepared a libretto for Marx’s oratorio Mose, but declined to perform the work when it was finished. Deeply offended, Marx wrote, “who could have predicted that our brotherly friendship would end in complete, deathly cold estrangement.” And he bitterly went on to destroy his entire correspondence with Mendelssohn.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Felix Mendelssohn: String Symphony No. 12 in G minor (Amsterdam Sinfonietta; Lev Markiz, cond.)

Mendelssohn visited Paris in 1825. Do you know if he met the Basque composer Juan Crisóstomo Arriaga, a pupil of Cherubini, while he was there? Even if they did not meet, Mendelssohn’s string quartets show the influence of Cherubini’s quartets (and vice versa), as also do Arriaga’s quartets.

What we know for certain is that Mendelssohn did indeed meet with another composer in Paris, 1825. Albeit possibly not Arriaga, but Cherubini! The possibility that the 16 year old Mendelssohn met with Arriaga is slim, but there is some record that implies there MAY have been a meeting of which Mendelssohn’s Octet in Eb Major would have possibly played. (As the work was published/premiered in 1826, it is likely that this performance was one only a select few were at; thus forth we have no CLEAR sign that the teenage Mendelssohn met with him.) I hope this helped to answer your question

My kindest regards,

T. Emmerson