Accomplished women composers of yesteryear wrote music that was highly regarded by both their male peers and the listening public in their day. These composers, who struggled for recognition, their works neglected for decades, deserve the accolades and attention they are beginning to receive from performers and audiences. I’d like to feature a few of my favorites!

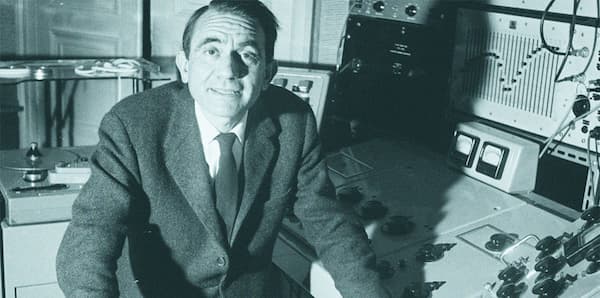

Nadia Boulanger

Nadia Boulanger’s Three Pieces: Beginning with contemplation and grace, these gorgeous semi-impressionistic pieces are perfect for the cello. Totaling just eight minutes, Three Pieces is a great opener to a recital. The cello plays muted in the first movement Modéré. Melancholy, and atmospheric there are hints of the influence of Fauré. The gentle second movement, Sans Vitesse et à L’aise, with ease, soothes us with its sweet, unpretentious melody. Then movement three, Vite et Nerveusement Rythmé quick and nervous, is energetic, rhythmic, and flashy. Originally written for organ in 1911, the pieces were transcribed for cello in 1914 by Boulanger herself and are most performed in that version. Boulanger (1887-1979), is arguably the most influential music pedagogue of the 20th century—a conductor, teacher, and composer and her students include a who’s who of the greatest musicians of our time including Daniel Barenboim, Aaron Copland, Philp Glass, Leonard Bernstein, Quincy Jones, and Astor Piazzolla. She wrote beautifully for the cello.

Nadia Boulanger: Three Pieces (Astrig Siranossian, cello; Daniel Barenboim, piano)

Dame Ethel Smyth © LGBT History Month Campaign

Dame Ethel Smyth’s Sonata in A minor Op. 5: A dramatic and substantial work, is dark and passionate. Equally paired with the piano, it’s full of syncopation and breathlessness, and uses the full range of the cello including the deep bass like Brahms’ cello sonatas—a composer she met and greatly admired. Smyth (1858-1944) was a character. Her family vehemently opposed her music-making and prohibited her further study, which they deemed quite unlady-like in its intensity. But she rebelled refusing to leave her room, refusing meals, and refusing to attend family gatherings until her father agreed to send Smyth to Leipzig to study composition. The 1887 Sonata, dedicated to the outstanding cellist of the day, Julius Klengel, is massive in scope and the three contrasting movements—an Allegro Moderato, a reflective Adagio non troppo, and a rhythmic Allegro Vivace—takes us through the gamut of moods and colors the cello renders so beautifully. Undoubtedly one of the UK’s most important composers, Smyth’s sonata was out of print for nearly a century and hardly performed until recently. Multi-talented, a prominent and vocal suffragette, Smyth also wrote ten books, and was the first woman composer to attain damehood!

Ethel Smyth: Cello Sonata in A Minor, Op. 5 (Friedemann Kupsa, cello; Celine Dutilly, piano)

Documentary on Dame Ethel Smyth

Mel (Mélanie) Hélène Bonis

Mel (Mélanie) Hélène Bonis’ Sonata for Piano and Cello in F major, Op. 67: Written in 1905 in Paris, at a time when very few women were allowed to study at the Paris Conservatory. It was thought that composing took too much mental energy for women! Bonis (1858-1937), brought up in a strict and religious family, taught herself piano. Later, a teacher at the conservatoire convinced Bonis’ parents to allow her formal music lessons. At age sixteen, Bonis, upon the recommendation of César Franck, entered the Conservatory studying in the same class with Debussy. Unfortunately, there she fell in love with a man her parents didn’t approve of. They withdrew her from school and married her off to a man twenty years her senior—a widower with five children. Once she had three children of her own, Bonis disappeared into obscurity until she could return to composing later in life. She chose the pseudonym and androgynous name “Mel” hoping her music might be played more often. The three-movement work is tender and elegiac, with an especially lovely second movement. Bonis focuses on the tenor range of the cello, where it can really sing. Full of ardor, the finale has the pianist take the spotlight with undulating passagework covering the entire keyboard— the piano alternating musical statements with the cello. Bonis composed over 300 works—chamber music, piano music, and orchestral and religious music, but her compositions have yet to be discovered by musicians and audiences alike! If you cellists will excuse me, the performance on the double bass below is wonderful too.

Mélanie Bonis: Cello Sonata in F Major, Op. 67 (Thomas Blees, cello; Maria Bergmann, piano)

Bonis on Bass really beautifully played!!

Henriëtte Bosmans © Leo Smit Foundation

Henriëtte Bosmans’ Cello Sonata: A stunning, romantic four-movement piece. Written in 1919, the sonata is one of several cello works from her early period and include: Nocturne for harp and cello (1921), two cello concertos (1922, 1923), and Poème for cello and orchestra (1923.) The sonata begins dramatically, the cello punctuated by huge chords in the piano. A vocal theme in the cello, the melody passionate, extents high onto the upper string with heartrending lamentation. It’s intense and enthralling writing. The second and third movements still lyrical, become more optimistic. A rhythmic and powerful last movement ends with a return to the dramatic opening of the first movement. The sonata is beautifully constructed and I love Bosmans’ use of the entire range of the cello, its lush eloquence no less than the major cello sonatas of the repertoire such as those of Brahms, Franck or Rachmaninoff. This sonata should be standard repertoire!

Henriëtte Bosmans (1895-1952) was born in Amsterdam into a musical family. Her mother played and taught piano and her father, a cellist, was the principal cello of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Bosmans studied piano with her mother and by the age of 20 she had established a career as a piano virtuoso. Imagine! She performed as soloist with the great conductors Ansermé, Mengelberg, and Monteux appearing 22 times with the Concertgebouw. Meanwhile she studied composition. As she developed, her works became more infused with polytonality, atmosphere, and unusual rhythms. With the impending war, and her refusal to join the Kultuurkamer, the Dutch counterpart of the Reishskulturkammer established to serve Nazi ideology, performance of her music was banned in 1942. She was not allowed to perform in public either, undoubtedly due to the fact that although her father was Roman Catholic, her mother was Jewish, and Bosmans was an avowed bisexual. She stopped composing. Despite these obstacles Bosmans’ oeuvre is remarkable and includes music for piano, violin, and flute with orchestra, as well as numerous pieces for cello and chamber music compositions. After the war, she focused on vocal works.

Join me for part II. I will feature several other wonderful cello works by women composers.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Henriette Bosmans: Cello Sonata (Doris Hochscheid, cello; Frans van Ruth, piano)

Thank You very much for this excellent article.

Thank you!

I very much appreciate all your work and the sharing of it.