Franz von Lenbach: Clara Schumann

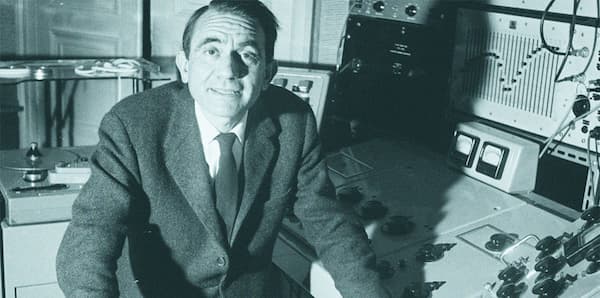

Clara Wieck-Schumann (1819-1896) confided in her diary, “a woman must not wish to compose—there never was one able to do it. Am I intended to be the one? It would be arrogant to believe that.” Her husband Robert was supportive of Clara’s creative efforts, but his opinion on her role was inflexible. “To have children and a husband,” he writes, “who is always living in the realms of imagination do not go together with composing. She cannot work at it regularly and I am often disturbed to think how many profound ideas are lost because she cannot work them out. But Clara herself knows her main occupation is a mother, and I believe she is happy in the circumstance and would not want them changed.”

Clara and Robert Schumann

Such attitudes have actively discouraged or even barred women from pursuing careers as composers for a very long time. It forced Clara Schumann, one of the most talented and distinguished composer-pianist of the 19th century into a “struggle for self-assertion and survival amidst competition, personal disappointments, devastating sorrow, and the challenges of managing both family and career.” Yet despite these obstacles, Clara and other women have persisted in writing music, and their achievements have been hiding in plain sight for centuries. Music by women composers, living or dead, was rarely heard in major concert events. Thankfully this embarrassing situation is gradually changing, and we decided to advance this matter by showcasing some of the most exiting chamber music compositions written by women. Let’s get started with the G-minor Piano Trio, Clara Schumann’s best-known compositions. Composed in 1846, it is her masterpiece and sadly one of the few multi-movement works in her catalogue.

Clara Schumann: Piano Trio in G minor, Op. 17 (Antje Weithaas, violin; Tanja Tetzlaff, cello; Gunilla Süssmann, piano)

Thomas Gainsborough: Franziska Danzi Lebrun

Franziska Danzi Lebrun (1756-1791) came from a highly talented musical family. Her mother Barbara Sidonia Margaretha Toeschi was a professional dancer and her father Innocenz Danzi a renowned cellist working at the Mannheim court. Her brothers Franz and Johann Baptist, in turn, were professional instrumentalists and successful composers. Franziska was trained as an operatic soprano, and she first publically appeared at the age of 16. Shortly thereafter, she was engaged by the Mannheim opera and highly sought after for her vocal dexterity. Contemporary composers such as Anton Schweitzer, Ignaz Holzbauer, and Antonio Salieri would cast her in leading roles in their most challenging operas. In 1778, Franziska married the composer and oboist of the Mannheim orchestra Ludwig August Lebrun. The couple frequently appeared in concert together, and played in Milan and Paris.

She sang on major operatic and concert stages throughout Europe to great acclaim, and the writer C.F.D. Schubart asserted that she could sing “A, three octaves above middle C with clarity and distinctness.” The family traveled to London in 1779, where Francisca sang at the King’s Theatre in operas by J.C. Bach and Sacchini. Her impact in London was such that the celebrated artist Thomas Gainsborough painted her portrait. However, her talents extended far beyond the stage to keyboard performance and music composition. That includes twelve sonatas for harpsichord with violin accompaniment published as her opus 1 and opus 2. First issued in London between 1779 and 1781, further editions were prepared in Paris and a number of German cities. Although not revolutionary, these charming chamber music compositions provide a delicious taste of mid to late 18th century musical taste. And did you notice that she shares her birth and death year with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart?

Franziska Lebrun: Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 1, No. 3 (Dana Maiben, violin; Monica Jakuc, fortepiano)

Victoria Bond

Victoria Bond (b. 1945) is an acclaimed composer, conductor, lecturer, and the artistic director of “Cutting Edge Concerts.” Major publications call her compositions “powerful, stylistically varied and technically demanding,” and her conducting “impassioned and full of energy and fervor.” In 2019, the Berlin Philharmonic Easter Festival in Baden-Baden, Germany premiered Bond’s opera Clara, based on the life of composer and pianist Clara Schumann. The German press wrote: “Victoria Bond gives each character a three-dimensional role, enriched with original musical colors.” Thus far, Bond has composed eight operas, six ballets, two piano concertos and numerous orchestral, chamber, choral and keyboard compositions. Victoria Bond is the first woman awarded a doctorate in orchestral conducting from the Juilliard School, and she has served with countless national and international symphony and chamber orchestras.

Victoria Bond

“Dancing on Glass” is based on the Chinese folksong Liu Yang River. It originates from Hunan Province and was a favorite of street musicians who often sang it accompanied by a drum. It also became the melody of a famous patriotic song celebrating Hunan’s most famous citizen, Mao Zedong. The song makes reference to the nine turns that the Liu Yang River makes before it flows into a lake. As such, the piece “is divided into nine sections, consisting of three solos, three duets and three trios.” According to the composer, “the title derives from the dance of light on the surface of the glass-like river. The sections flow into each other without a break, reflecting the changing character of the river.”

Victoria Bond: “Dancing on Glass” (Anna Cromwell, violin; Lisa Nelson, viola; Mira Frisch, cello)

Nadia and Lili Boulanger sisters, 1913

For a very long time, the famous Prix de Rome competition was closed to women. Only in 1903 did the Education Minister Joseph Chaumié make the surprise announcement at a press dinner that the Prix de Rome would be open to women from that year. This unexpected announcement took the “Académie” by complete surprise, and they mercilessly schemed to prevent women from receiving that coveted prize. After her sister Nadia gave up her attempts to win the Prix de Rome, Lili Boulanger (1893-1918) decided to compete for the prize. She studied privately and at the Conservatoire, and after an unsuccessful first attempt in the 1912 competition, she won the Prix de Rome in 1913. She was the first woman to win the prize for music, and her success made international headlines. As the local press wrote, “The suffragettes smash windows and burn houses, but a maiden of France has gained a much better victory.”

Lili Boulanger

Already in early childhood, Lili fell ill with bronchial pneumonia, and she was almost constantly ill for the rest of her life. “Her frail health conditioned her life, through the need of constant care, and her musical career, as she had to rely on private composition and instrumental tuition rather than a full musical education.” But while her dependence on others was often overwhelming, she did enjoy complete intellectual and artistic autonomy. Lily once wrote, “I feel discouraged … not because of the suffering, not because of boredom, but because I understand that I would never be able to have in me the feeling that I have done what I would like to do, but what I have to do, since I cannot follow whatever it is with being interrupted for a long time so that my efforts cannot be sustained!” Lili did compose over 50 works, and her “D’un soir triste” exists in two fabulous versions: one for violin or flute and piano, the other for cello and piano.

Lili Boulanger: “D’un soir triste” (Boulanger Trio)

Teresa Carreño

Teresa Carreño (1853-1917) originally hailed from Caracas, Venezuela, but her family moved to New York in 1862. Teresa had a highly ambitious father, and she demonstrated extraordinary talent for piano performance, improvisation, and composition. She became a student of Louis Moreau Gottschalk, and was playing before President Abraham Lincoln at the White House when she was ten years old. The family moved to Paris in 1866, and Carreño played for Franz Liszt. He told the young prodigy, “My dear little Teresita, God has surely given you the greatest gift of all, that of genius. Work, develop your talents, but above all stay true to yourself, and in time you will be one of us.” Carreño performed in concerts throughout the world, and she was “among the first female pianists to tour the United States.”

Carreño served as a role model for new generations of American women who entered musical life as professional performers and composers. In fact, Carreño composed approximately 80 works that mostly date from the early stages of her career. She included them in her concerts, and “they reflect the influence of the style of virtuoso composers, especially Gottschalk, along with an assimilation of Venezuelan rhythmic and formal elements.” Although she mainly composed for the piano, Carreño did approach larger forms in her serenade for string orchestra and her delightful String Quartet in B minor. A scholar writes, “ In 1896, Teresa Carreño, the famous piano virtuosa composed a string quartet which shows a thoroughly sound grasp of quartet technique and style, Particularly praiseworthy is the concise construction of each of the four movements… From the time of its first appearance, this Quartet has received considerable notice.”

Please join us next time for more chamber music composed by women, including works by Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, Julia Frances Smith, Germaine Tailleferre, Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen, and Mélanie Bonis.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Teresa Carreño: String Quartet in B minor (Joseph Roche, violin; Robert Zelnick, violin; Tamas Strasser, viola; Camilla Heller, cello)