When Carl Reinecke published the first of his well over three hundred works in the 1830s, Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Liszt were at the height of their fame. Such was Reinecke’s longevity that when his final scores were printed, Schoenberg, Webern, Berg as well as Scriabin and Debussy were probing new musical directions. His death in 1910 hardly raised a byline in the press, so we decided to properly celebrate his 200th birthday on 23 June 2024 with a dedicated feature exploring a highly versatile composer who is represented in virtually every musical form of his time.

Carl Reinecke: Flute Sonata “Undine,” Op. 167

Reputation

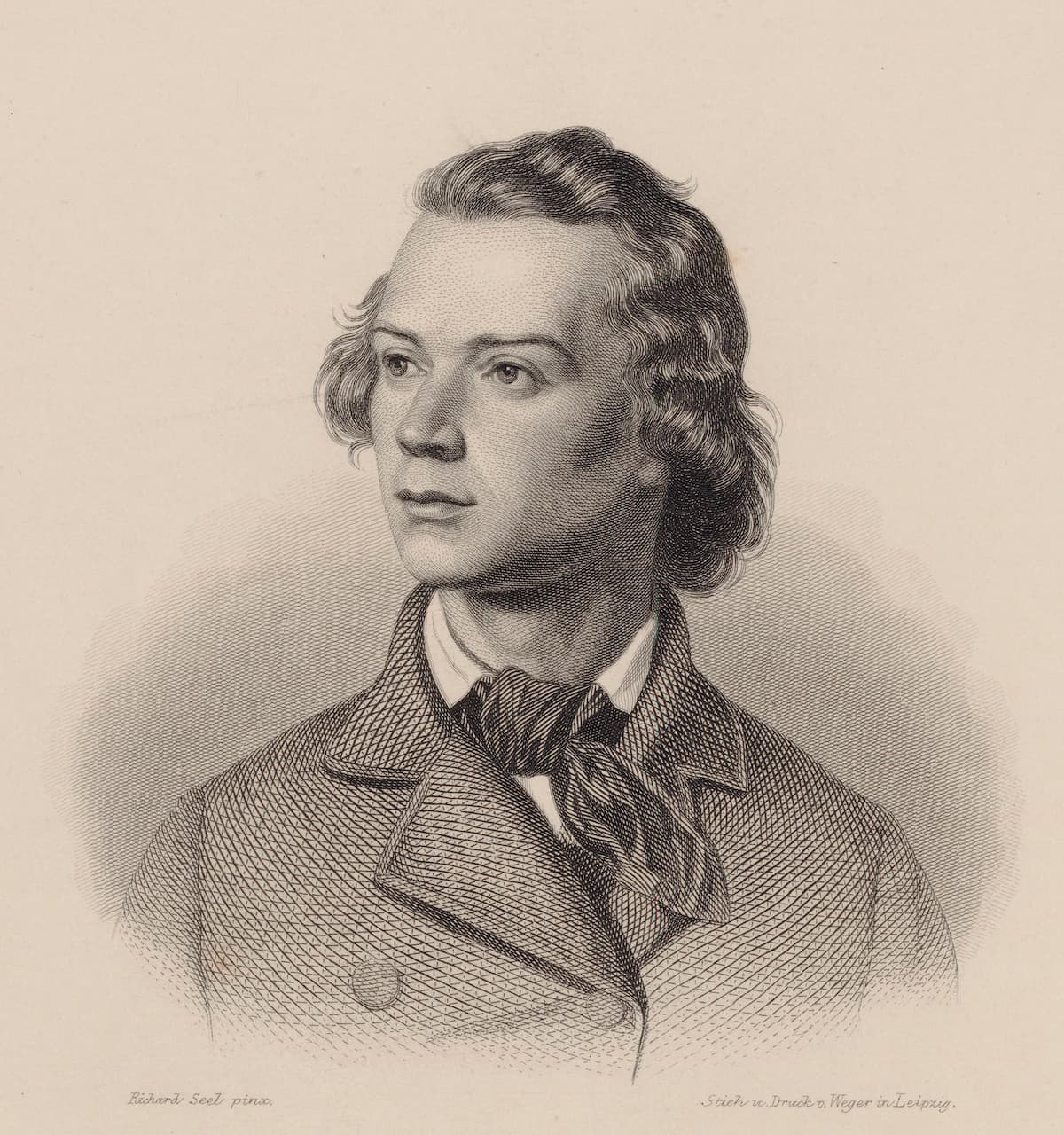

The young Carl Reinecke

During his lifetime, Carl Reinecke was held in the highest regard. Here is what a critic had to say after a 1871 concert at the Hanover Square Rooms. “The composers whose works have been selected from have been Volkman, J. Brahms, Rubinstein, Reinecke, etc., all of whom have been well represented, some showing us what they can do, and others what they cannot do. Were we to express our individual opinion, we should unhesitatingly declare that we do not care if we never hear another note of Volkman or Rubinstein again. J. Brahms and Reinecke are creative artists of whom we have a right to be proud, although the clear and musician-like writing of the latter is in our judgement infinitely superior to the somewhat forced and exaggerated style of the former.” In 1871 and England, Reinecke was ranked above Brahms.

Carl Reinecke: Piano Quintet in A Major, Op. 83 (Linos Ensemble)

Childhood

Born in Altona, near Hamburg on 23 June 1824, Carl Reinecke and his sister Betty grew up with their father, as their mother died of consumption in 1828. By all accounts, J.P. Rudolf Reinecke, a respected music theorist and author of several textbooks, was a strict taskmaster. Both children were home-schooled, and in addition to the usual subjects, he also gave his children musical instruction.

Betty wrote in her diary, “his eagerness to teach bordered on fanaticism, he felt best when he was teaching. But it must be said that we went through hard and sad hours with our irritable father. I suspect that he made exaggerated demands of us, especially because we children followed him so willingly.”

Carl Reinecke: 4 Stücke, Op. 214 (Genova and Dimitro Piano Duo)

Leipzig

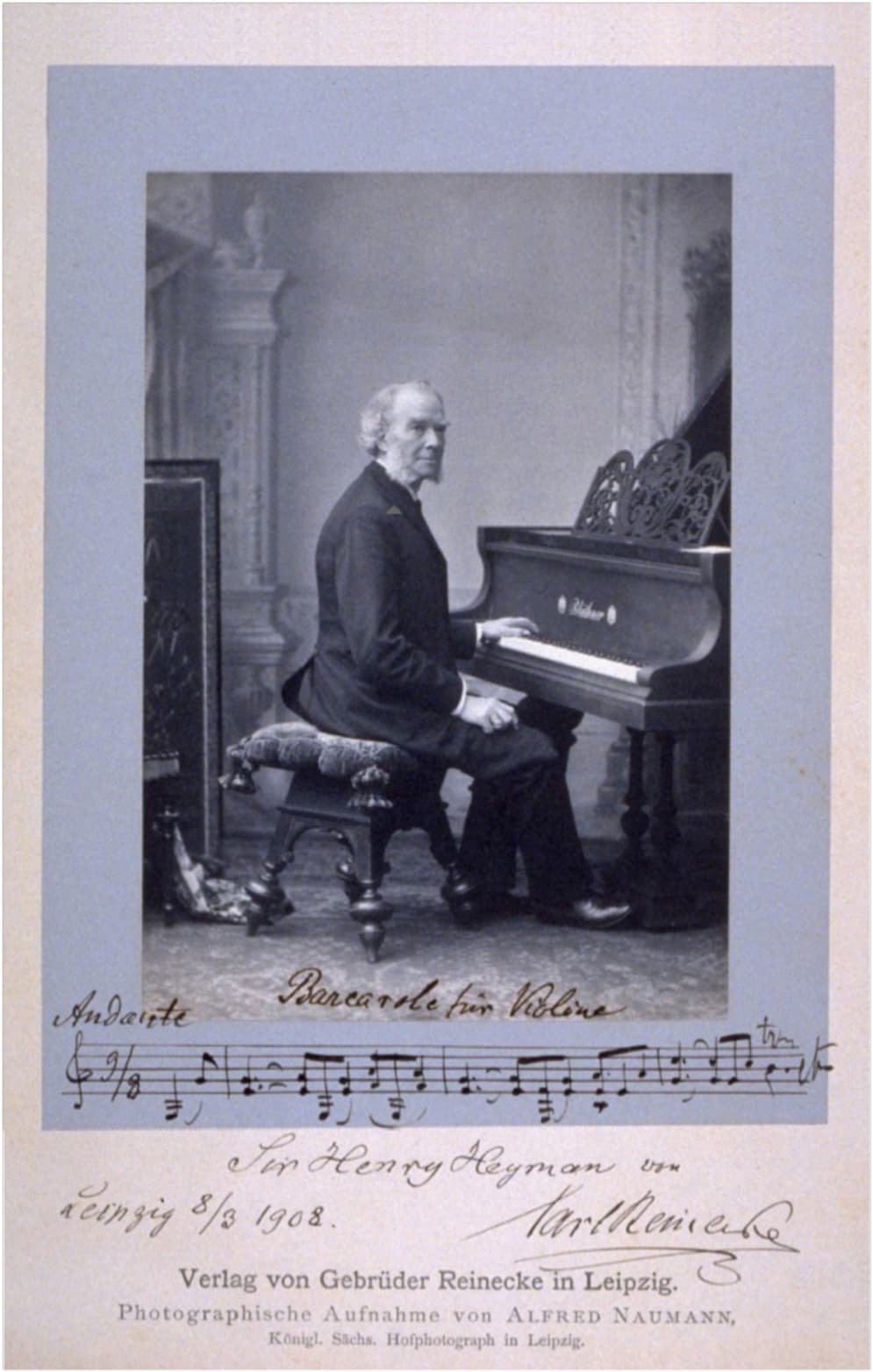

Carl Reinecke

Carl had inherited the delicate and sensitive constitution of his mother and he later explained, “my father’s strictness and his habit of breaking my will by recognizing only his own will as the solely valid one, made me throughout my whole life into a much too soft and compliant nature. I often only had enough energy to prove things to myself, I was much too weak against others, often to my detriment.”

When Carl heard Clara Wieck in 1835 and Franz Liszt in concert in 1841, he decided to become a concert pianist himself. Although his father objected vigorously, young Carl took his first classes at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, and the director Felix Mendelssohn enabled a performance for piano and orchestra for Reinecke in 1846. Reinecke was deeply drawn to the music of Robert Schumann, and according to Schumann “Reinecke understands me, like few others.”

Carl Reinecke: Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 134

Years of Travel

Starting in 1845, Reinecke embarked on a number of concert tours, and he was appointed Royal Court Pianist in Copenhagen between 1846 and 1848. He briefly returned to Leipzig to play a few concerts at the Gewandhaus, and in Weimar he met Franz Liszt. In fact, Reinecke would subsequently teach Liszt’s daughter in Paris, and she reported on his “beautiful, gentle, legato and lyrical touch.” Reinecke also appeared in Bremen, playing four-hand recitals with Clara Schumann, and collaborating with Jenny Lind.

After a brief period in Paris, Reinecke was engaged as a piano and composition teacher at the Cologne Conservatoire between 1851 and 1854. He gave concerts with Ferdinand Hiller, and on his friend’s recommendations, he took over the musical directorship of several music societies at Barmen. Reinecke also spent ten months in Breslau as director of music at the university and conductor of the Singakademie.

Carl Reinecke: Piano Concerto No. 4 in B minor, Op. 254 (Simon Callaghan, piano; St. Gallen Symphony Orchestra; Modestas Pitrėnas, cond.)

Leipzig Conservatory

Concert by Carl Reinecke in the New Concert House (1884)

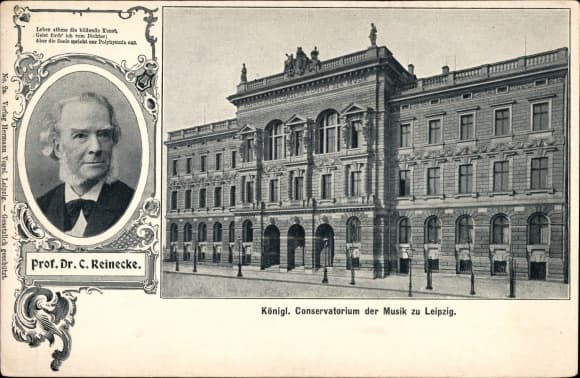

In 1860, Julius Rietz resigned his position as Gewandhaus director in Leipzig. Reinecke’s growing reputation secured him an appointment, and he was soon a recognised and highly-regarded force. Reinecke appointed highly capable teacher who shared his conservative views, and he greatly improved the facilities and the syllabus.

Reinecke considered it his responsibility as director to represent and guard the tradition of the Classical composer. He strongly championed the music of pre-Classical composers, particularly Bach and reaching back as far as Palestrina. As a teacher, he firmly believed in a thorough grounding, and as a stern disciplinarian, he achieved a high standard of virtuosity from his players.

Carl Reinecke: 3 Pieces for Cello and Piano, Op. 146 (Martin Rummel, cello; Roland Krüger, piano)

Pedagogy and Assessment

During Reinecke’s reign, he transformed the Leipzig Conservatory into one of the most renowned and respected institutions in all of Europe. He counted Grieg, Kretzschmar, Kwast, Muck, Riemann, Sinding, Svendsen, Sullivan and Weingartner among his students. Reinecke was equally eminent as a conductor and considered a gifted interpreter of the music of Schumann and Brahms. He did proclaim himself reserved with respect to the more modern school of Liszt and Wagner, with Leipzig gaining the reputation as a hotbed of reactionism.

When Tchaikovsky visited Leipzig, he reports back home. “Reinecke enjoys in Germany and indeed in all Europe the reputation of being an outstanding musician, a talented composer and an experienced conductor, who has succeeded with great dignity, albeit without any particular brilliance. I say without any particular brilliance because many people in Germany deny that Herr Reinecke has any gifts as a conductor, and would like to see him replaced by a more passionate musician, with a more resolute and stronger character. However that may be, there is no doubt that Reinecke is one of the most influential and prominent figures in the German music world.

Carl Reinecke: Clarinet Trio in A Major, Op. 264 (Olivier Dartevelle, clarinet; Pierre Henri Xuereb, viola; Jean Schils, piano)

Compositions

Collectible Postcard of Leipzig Conservatory in Its New Facilities 9

Reinecke received an honorary doctorate in 1884 and he became a professor in 1885. He retired from academic duties in 1902, but he continued his creative work until the end of his life. Reinecke is still known for a myriad of didactic compositions, with his exercises for young pianists and the piano sonatinas enjoying great popularity. Influenced by Mendelssohn’s melodic style, these pedagogical works are “highly inventive and totally free from bourgeois sentimentality.”

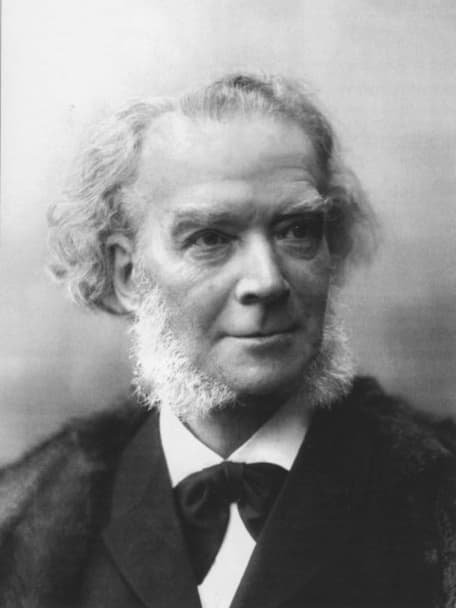

Carl Reinecke, 1890

Undoubtedly, his sonata for flute and piano subtitled “Undine” is his most frequently performed work, and one of very few pieces that have maintained their position in the concert repertoire. Critics consider his concertos for flute and for harp as his most successful, while the piano concertos “avoid grand soloistic mannerisms, and his own style playing, with hands still and fingers curved, reflected his belief in classical practice.” Reinecke also contributed three symphonies, but his operas were not successful. His chamber music, however, is rather distinguished and glows with a Brahmsian majesty and warmth.

Carl Reinecke: String Quartet No. 5 in G minor, Op. 287 (Reinhold Quartet)

Self-Assessment

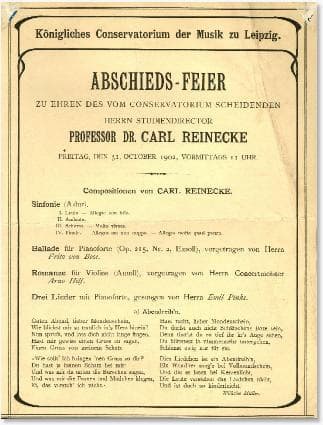

Carl Reinecke: Farewell Concert, 1902

Reinecke was a talented painter and poet, and he authored a number of books and various essays. In fact, he was one of the pre-eminent scholars and performers of Mozart’s music. Contemporary history, however, has never forgiven him for not participating in new musical developments for decades. As he summed things up in connection with a statement about his fellow composer Ferdinand Hiller. “his main weakness was that he wrote too hastily; he let one work follow the next without a break, always in the hope that he would create a greater work, one that this time would have to meet with a sensational success.”

Reinecke continues, “I too face with resignation that many of my works have been mostly laid ad acta, even though I can testify with good conscience that I have shunned neither effort nor work or time in order always to bring my works to the highest degree of perfection reachable by me.”

Carl Reinecke died on 10 March 1910 at the age of 85. He left behind a rich artistic legacy that influenced various areas of music, including performance and composition. His works are rightfully celebrated for their melodic beauty and depth, attributes that really should no longer be counted against him in the 21st Century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter