A recent work by American composer George Crumb (1919-2022) looked at 10 famous paintings dating from 1872 to 1990. Metamorphoses (Book I), subtitled Ten Fantasy-Pieces (after celebrated paintings), was composed between 2015 and 2017 for amplified piano.

Crumb himself pointed to Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition for his model in transforming sight into sound. His response to the paintings is about the ethos, i.e., the characteristic tone of the painting and its title, rather than trying to create a precise musical reproduction of the art, if that would even be possible.

The artist covers works by Paul Klee, Vincent van Gogh, Marc Chagall, James McNeill Whistler, Jasper Johns, Paul Gaugin, Savador Dalí, and Wassily Kandinsky.

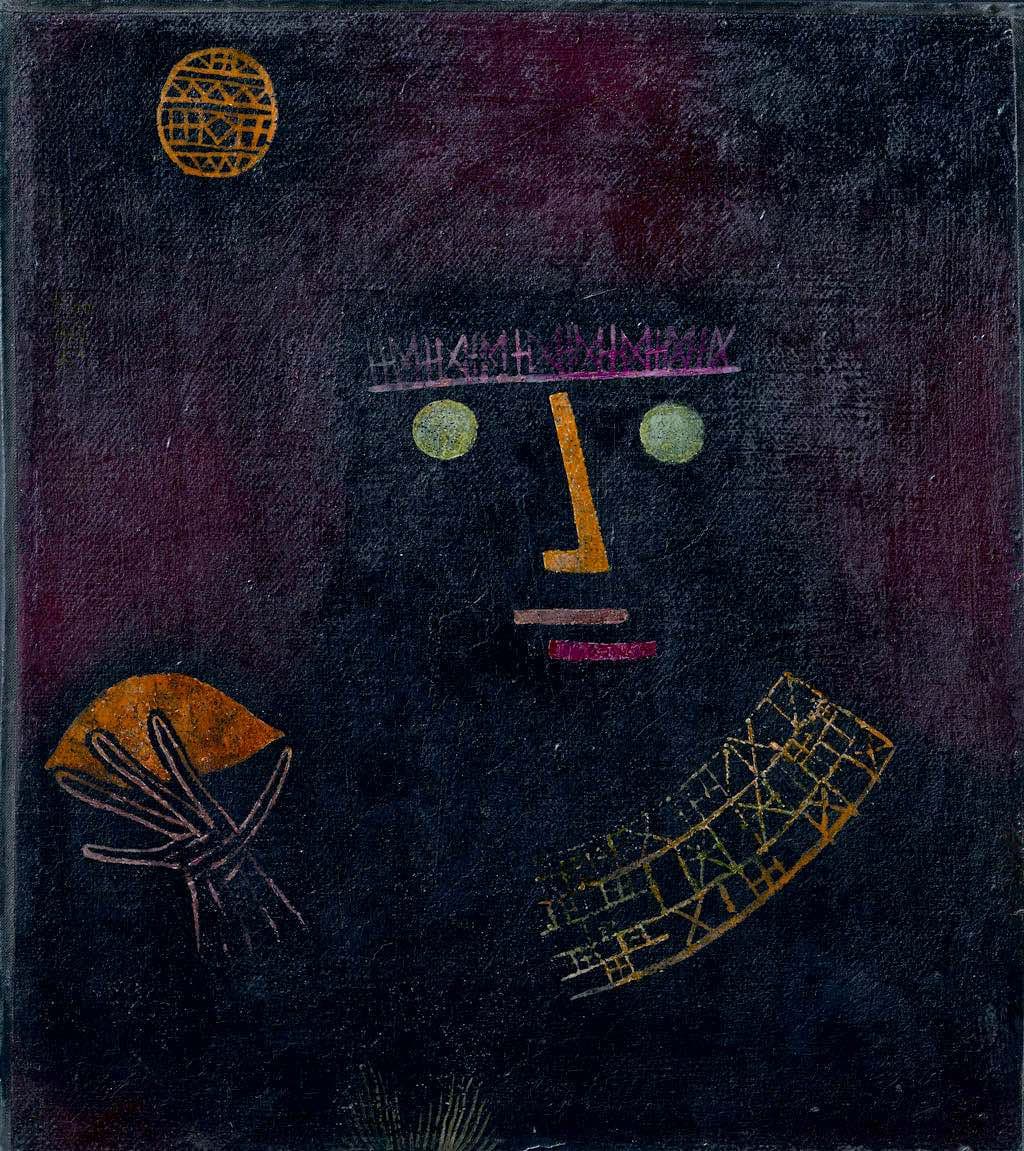

Paul Klee’s Schwarzer Fürst (Black Sovereign) was created in 1927 and through the use of geometric forms, Klee brings us a ruler in his crown, dressed in an ornate robe, holding a sphere, with a sun overhead. The geometry in the work was a large part of Klee’s work in the 1920s. The figure is enigmatic – is he of this world or a ruler in a private world of Klee’s? Can the signs on the headdress and the clothing have meaning? If the face is comprised only of two eyes, a nose, and two lips, why is the hand so carefully delineated? As the viewer goes through these mysterious references, he constructs his own world around these geometric lines.

Paul Klee: Schwarzer Fürst, 1927 (Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany)

In his musical rendering, Crumb also begins with a few bold notes, seeming to work like an incantation. The low notes and dark timbres put us in the world of the painting. Advanced piano techniques have pianists play the keys as much as the strings of the piano, calling for muted and unmuted tones; plucked, strummed, and scraped strings; striking the strings with the palm of the hand; and harmonics. Occasional music at the top of the piano brings us sudden shots of light. Crumb said he associates this composition with Africa and with the man he calls the ‘modern “black prince”’, Nelson Mandela.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 1. Black Prince (after painting by Paul Klee, 1927) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

Crumb stayed with Klee for the next piece painted two years earlier, entitled Der Goldfisch (The Goldfish). In the middle of a blue-black sea, a golden fish shines out. The other fish, variously red and purple, swim away from it, as though blinded by its brilliance. The fish are all built out of the simplest of materials, wavy and zigzag lines, and the plants are equally simple. Although, at first, all we can see is the brilliant goldfish, gradually the other details start to appear, but take a while to emerge into our consciousness. Klee was fascinated by aquariums, calling them ‘sea in a glass’ and had an aquarium in his Dessau studio as he was creating this work.

Paul Klee: The Goldfish, 1925 (Hamburger Kunsthalle, Germany)

In creating his goldfish, Crumb had as an example Debussy’s Images, Book II, and its ‘Poissons d’or’ movement. In his music, Crumb attempted to recreate the darting motions of the real fish, something that Klee did not portray in his painting. Technically, the pianist has to change the sound of the piano by using the middle pedal – this holds the dampers off the piano’s lowest strings and creates a shimmering background behind the movement of the fish.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 2. The Goldfish (after painting by Paul Klee, 1925) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

Moving back in time, Vincent van Gogh’s 1890 painting Wheatfield with Crows is the next image of inspiration. One of Van Gogh’s last paintings shows a wheat field under threat not only from the thieving crows but also from the impending storm. It is a picture of brilliant colours in opposition and combination: the blue/black sky, the angles of the black crows, the bright yellow wheat, the red path, and its green edging. Van Gogh saw these ‘vast expanses of wheat under stormy skies’ as being filled with sadness and giving a sense of extreme solitude.

Vincent van Gogh: Wheat field with Crows, 1890 (Van Gogh Museum)

Crumb saw the work as being ‘suffused with a sense of death’, and through his piano setting, tries to bring to music van Gogh’s brushstrokes. The music is marked ‘Lento elegiac (uncanny, forbidding)’ and to enhance that feeling of the uncanny, the technical requirements include directions to the pianist to slide a percussionist’s wire brush across the low bass strings, strike the crossbeam repeatedly with a yarn-headed percussion stick, and imitate the caw of the crows. The textures shift – some sections are sharply drawn and others float in a blur.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 3. Wheatfield with Crows (after painting by Vincent van Gogh, 1890) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

Marc Chagall’s 1912–13 painting Le violiniste (The Fiddler) was painted when the artist lived in France, but it depicts Chagall’s home village of Vitebsk in Russia (now Belarus). The painting is enormous (196.5 x 166.5 cm / 6.5 x 5.5 feet) and shows a fiddler in the foreground, seeming to stand on a house, while the whole village behind him has been foreshortened into a flat plane. It’s full of Russian images, yet presented in a cubist perspective. The violinist represents the social crossroads that music can mark in life: at birth, a wedding, and a death. The colours, like those in van Gogh, are strong but dominated by the white patches of winter on the roofs, set off by black and brown in the buildings and the shadows on his coat. The fiddler’s face is blue and green and he’s playing an orange and yellow violin. Touches of red appear on his hat and a distant building. The curve beneath his feet could be the village commons or represent the earth, supporting the universality of music.

Marc Chagall: Le Violiniste, 1912-1913 (on loan: Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam)

Crumb’s fiddler opens with a bit of strumming and tuning and those tuning notes become the resonant core of the work. Crumb invokes the sound of Russian/Jewish folk tunes in little bits and fragments but it’s the open fifths, first heard in the opening tuning section that dominates the work.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 4. The Fiddler (after painting by Marc Chagall, 1912-13) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

American artist James MacNeill Whistler used musical titles for his work, including his Nocturne series. This series formed his first steps towards abstract art and in his 1872 work, Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Southampton Water, he shows us an inlet on the English Channel as night approaches. The boats in the channel are reduced to shadowy shapes while lights reflected in the water are the only bright points. The moon rises in the background, making the foreground seem even darker in comparison. Whistler gives the darkness a tonal harmony through his use of various shades of blue as night falls.

James McNeill Whistler: Nocturne: Blue and Gold–Southampton Water, 1872 (Art Institute of Chicago)

Whistler’s painting was answered with hushed chords coming from strummed strings. The pianist’s use of muted fingertips and more percussive fingernails gives a subtle texture to this night music. The golden points of light emerge from sounds in the upper register of the piano and the reflections on the water in Whistler’s work, indistinct and shadowy, appear in Crumb’s work through his use of varied imitation.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 5. Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Southampton Water (after painting by James McNeill Whistler, 1872) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

Jasper Johns was inspired to create Perilous Night after John Cage’s 1945 composition The Perilous Night, written during a time of great personal upheaval in Cage’s life. Johns’ work is a two-part multi-media abstract painting. On the left is a rectangular field that ‘is mottled with steel and charcoal grey streaked with white and amethyst purple’ (description from National Gallery of Art). The right-side field is divided horizontally and vertically with the bottom section painted to resemble wood grain. At the top of the right side are casts of three human arms that have been covered with patches of grey paint, almost like camouflage. Each arm is painted a different colour (red, yellow, blue) at the top and this coloured paint has dripped down and splattered both on the hands and on the faux-wood panel at the bottom. More to our interest is what is under the right-most arm: ‘a sheet of music overlapping another piece of paper printed with the letters “OHN C” and “THE PERILOUS” ‘(National Gallery). This score has been silkscreened onto the painting and gave Johns the title of the work.

Jasper Johns: Perilous Night, 1990 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

Pianist Margaret Leng Tan brought the painting to the attention of George Crumb who responded with his own Perilous Night. Margaret Leng Tan is the dedicatee of the entirety of Metamorphoses, Book I. Opening with the direction ‘Molto vivace (fearfully, with dark energy)’, the shadow feeling is emphasized, and it’s underlined with the direction to hold the damper pedal down so that all strings vibrate freely. A low drone is created by scraping and sliding on the bass strings, while above it, rapid chromatic figures dance. Crashes in the bass are answered by dancing chromatic treble lines. The work ends with two different sounds, one made by slamming the forearms onto the white and black keys and the other generated by laying a metal chain across the strings, buzzing perhaps in a reference to Cage’s original work for prepared piano.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 6. Perilous Night (after painting by Jasper Johns, 1990) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

Marc Chagall returns with his tragic image of Clowns at Night. Darkness pervades and is relieved only by the fiddler’s face and hand and his violin. Behind him, is another white-faced figure lifting her voice in song. Other music makers start to emerge out of the background: a figure on the right playing a pipe, and another in the back centre on a similar instrument. Next to the violinist is a figure with a bird’s head, who carries the singing woman. Like so many of the pictures used by Crumb for inspiration, this one, too, reveals more and more detail as one examines it. More people appear, and now the sad-faced violinist seems to be leading a procession of musicians, who trail behind him in the dark.

Marc Chagall: Clowns at Night, 1957

The tempo marking for this piece matches Chagall’s image: ‘In a lazy ‘Blues’ tempo, languid, seductive, ghostly’. The piano is played from the outside and the inside, starting with string glissandos and augmented with additional sounds coming from a woodblock mounted on the internal body supports and the shiver of metal wind chimes. A toy piano contributes its own particular cacophony.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 7. Clowns at Night (after painting by Marc Chagall, 1957) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

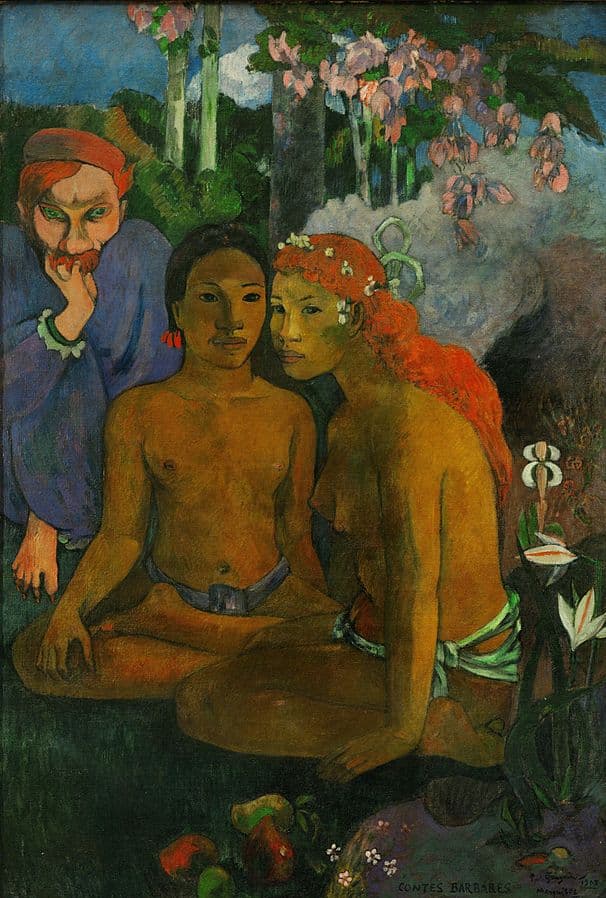

Paul Gauguin’s love for the South Pacific and his fascination with Polynesian culture took impressionism around the world. In Contest barbares, painted in 1902, he mixes the present and the past. At the right is Gauguin’s model Tohotaua, shown with red-orange hair that seems luminous. At the left is his friend, the Dutch painter Meijer de Haan, who died in 1895. Life on the right and death on the left, and in the middle, a woman who sits in the lotus position. Behind the three figures are clouds and strikingly beautiful flowers. All three figures look only at the viewer, concentrating their gaze at the artist. A watercolour version of this in Gauguin’s notebooks had written above it Le contour parle (the storyteller speaks). Some see other death symbols in the picture, such as the fruit (or is that an offering?), the flowers (to celebrate both life and death in the western tradition), and the departing cloud.

Paul Gauguin: Contes barbares, 1902 (Essen: Museum Folkwang)

Crumb created a 4-part work. Starting the idea of the storyteller speaking, he opens with ‘The Storyteller Invokes a Vision’; the second part, ‘Tahitian Death Chant: Spirit of the Dead Watching’ has the pianist simultaneously playing the keys while holding a felt-covered stick against them to mute them. The pianist also says ‘Manaò tupapaú!’, which Gauguin had used as the title for multiple works a decade earlier, translating it to mean ‘Think of the Ghost’, or ‘Spirits of the Dead are Watching’. The Storyteller’s tale returns again before the final section, ‘Tahitian Dance: Myth of the Moon (Hina) and the Earth (Fatou)’

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 8. Contes barbares (after painting by Paul Gauguin, 1902) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

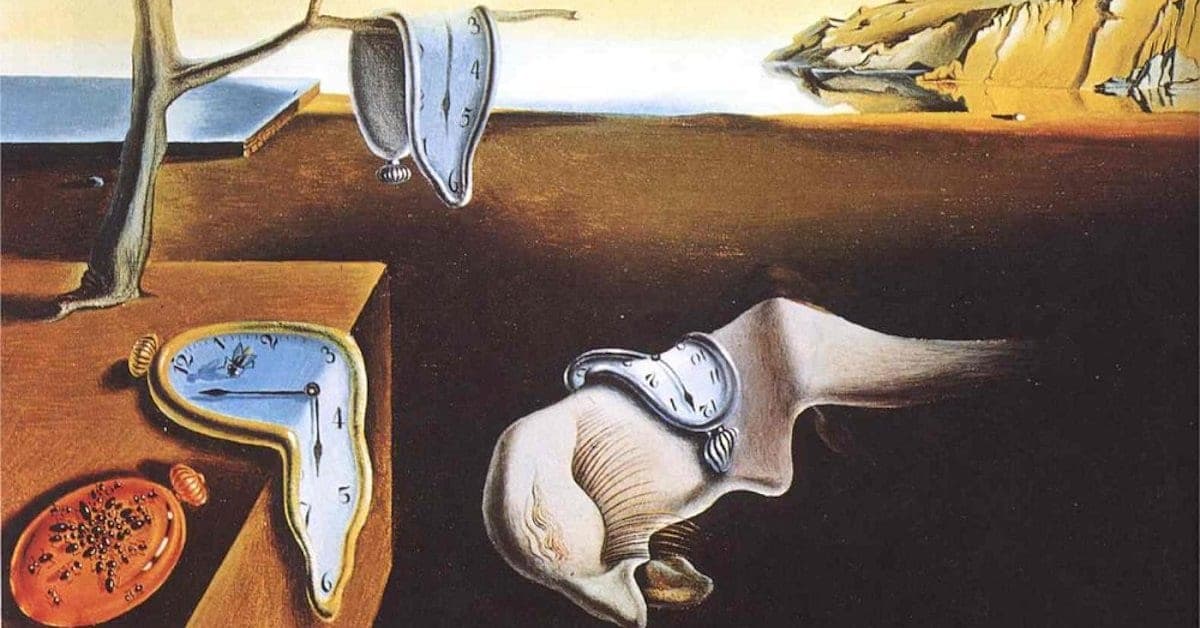

The Persistence of Memory is probably one of the first pictures by the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí that many people encounter. ‘Hard objects become inexplicably limp in this bleak and infinite dreamscape, while metal attracts ants like rotting flesh’ says the museum description and so we see the flowing pockets watches, draped over trees, over blocks, and over a section of Dalí’s own face. The ants, a symbol of decay, focus their attention on a gold watch, to only one without a numbered face, close to its attackers. In this attempt to completely discredit the world of reality, Dalí achieved a classical Surrealist goal: reality (the cliffs are from the coast of Catalonia, Dalí’s home) and unreality combined and you end up questioning the reality while accepting the unreality. Dalí commented: ‘The difference between a madman and me,’ he said, ‘is that I am not mad.’

Salvador Dalí: The Persistence of Memory, 1931 (MoMA)

Crumb responds to Dalí’s dreamlike atmosphere with his own shadow world, invoked by having the pianist play on the keys and the strings simultaneously. The distorted self-portrait by Dalí of Dalí is reflected by Crumb in his inclusion of music that recalls classical composers and compositions: a faint fragment of Mozart’s clarinet concerto is a reference to Crumb’s clarinetist father, a bit of Beethoven recalls all the sonatas Crumb learned in his student years, and the hymn tune ‘Amazing Grace’ is an echo of a beloved melody from his native Appalachia, where the pianist plays and hums it at a delay.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 9. The Persistence of Memory (after painting by Salvador Dalí, 1931) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

A blue-cloaked rider on a white horse races across a green meadow. White clouds float in a blue sky and birch trees grace the top of the hill. Further forests retreat into the background. Der blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) was the last impressionist painting by Wassily Kandinsky as he made his way to modern abstract art. The name of the painting became the name for the group of modern artists founded by Kandinsky in 1911.

Wassily Kandinsky: Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), 1903 (private collection)

The urgency of the rider is caught in Crumb’s agitated rhythm. The bass notes gallop louder and louder until chords appear in the treble register. The pianist’s palm hits the lowest keys of the piano in grumbling chord clusters before the pianist attacks the strings themselves with a yarn-covered percussion mallet (right hand) while his left-hand pounds out a thunderous low-note ostinato. It all ends in loud chords that provide a satisfactory close to the whole cycle.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 1 – No. 10. The Blue Rider (after painting by Wassily Kandinsky, 1903) (Marcantonio Barone, amplified piano)

Crumb isn’t illustrating the artworks with music, he’s augmenting the artists’ visions. In the last piece, we can see the sense of urgency in Kandinsky’s Rider, but it’s Crumb who gives us the larger picture and makes us think not only about what the Rider might be fleeing, but what lies ahead of him. The year after Crumb finished Metamorphoses, Book I, he started Book II.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter