Along with the production of orchestral and opera music in the 19th century, there was a parallel industry that made the same music for smaller forces: piano, piano two-hands, string quartet, small wind ensembles, etc. In the centuries before, music all around us poured from our radios or audio systems; if you wanted to hear some Mendelssohn, you had to play it yourself.

The home piano was an institution by the late 18th century and through the 19th century, only became more popular. In house construction, a wall in the front parlour would be left blank – no radiator, no decoration – so that there was a place for the piano.

1890 house with piano wall

In some houses, the blank space above an upright piano might be designed with a high window to bring in light and yet not disturb the setting of the piano.

The creators of the other versions might be the composer or his student or someone hired by his publisher to push the sales to a new market. In one history of the period, a writer summarized the situation as:

The only way to satisfy this demand was to create new versions of works that kept close to the core of the original compositions but did not require a full orchestra to perform them. This trend was not new: it had begun toward the end of the 18th century, but the trickle of published arrangements had now become a flood. By 1844, there were more than 9,000 arrangements of works of various kinds in circulation, including symphonies, concertos, overtures and even operas.

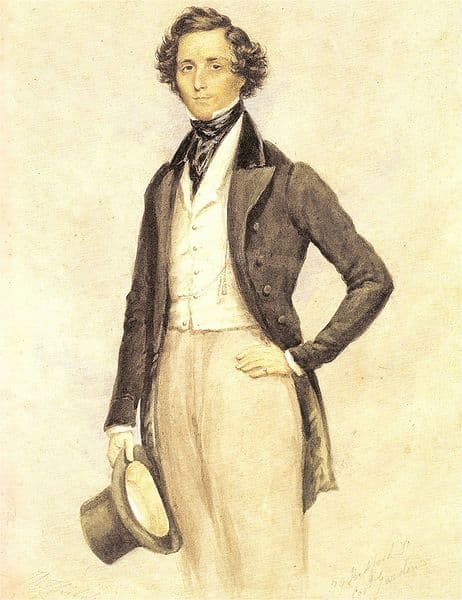

Following the end of the 1829 London concert season, the 20-year-old Mendelssohn struck north to see the wonders of Scotland. In the Hebrides by the beginning of August, he was quickly struck with a melody that became his concert overture, The Hebrides.

J.W. Childe: Felix Mendelssohn, 1829

Felix Mendelssohn: The Hebrides in D Major, Op. 26, MWV P7, “Fingal’s Cave” (Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; Vladimir Jurowski, cond.)

In addition to being a composer, Mendelssohn was considered one of the great pianists of his era. He created the four-hand version of his overture himself. What is of interest, of course, is not the great orchestral crescendos, but the emergence of the little countermelodies that often get buried in the orchestral excitement. In the 4-hand versions, you have more of a glimpse into the little background melodies.

Felix Mendelssohn: The Hebrides in D Major, Op. 26, MWV P7, “Fingal’s Cave” (version for piano 4 hands) (Franziska Lee, Sontraud Speidel, piano)

It wasn’t just 18th and 19th-century music that was rewritten for other forces, but also 20th-century music.

Aaron Copland’s ground-breaking El Salón México, completed in 1932, was given its premiere in 1935 in a two-piano version ahead of its orchestral premiere in 1936 in Mexico City with Carlos Chávez conducting the Orquesta Sinfónica de México.

Aaron Copland: El salon Mexico (New Philharmonia Orchestra; Aaron Copland, cond.)

An arrangement of the work for 2 pianos was made by Leonard Bernstein in 1943 (he’d also made a solo piano reduction in 1941). Copland’s 2-piano version from 1935 was the original version that was later revised for the orchestral premiere.

Bernstein and Copland, 1945 (Library of Congress)

Aaron Copland: El salon Mexico (arr. L. Bernstein for 2 pianos) (Maki Namekawa, Dennis Russell Davies, pianos)

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2, written in 1802, was one of the pieces that marked Beethoven’s ‘middle period’ as he improved as a composer. The Allegro molto final movement is marked by very quick string passages.

Christian Horneman: Ludwig van Beethoven, 1803 (Beethovenhaus Bonn)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36 – I. Adagio molto – Allegro con brio (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

The version for piano trio was made by Beethoven himself and caused a particular re-emphasis on the opening gesture. It is said that this symphony was written at a time of great stress for Beethoven and stress made him gaseous, so the opening has been interpreted as a hiccup or a belch followed by a groan of pain. Suffer the mighty composer.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36 (arr. L. Beethoven for piano trio) – IV. Allegro molto (Tim Brackman, violin; Pieter de Koe, cello; Hanna Shybayeva, piano)

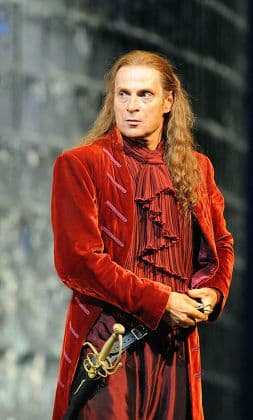

If you had four friends and you happened to be a string quartet, then all sorts of possibilities opened to you. Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni was arranged for string quartet – not just the overture, but all the major arias as well.

Simon Keenlyside as Don Giovanni, 2008 (Royal Opera House, London)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni, K. 527 – Act I Scene 5: Aria: Madamina, il catalogo e questo (José Van Dam, Leporello; Paris National Opera Orchestra; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

It could be considered rather as a ‘music-minus-one’ where the string quartet could sing along! Or get a singer.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni, K. 527 (arr. J. Went for string quartet) – Act I: Aria: Madamina, il catalogo e questo (Artis Quartet)

Or, it could be arranged for wind ensemble. It all depends on how many friends you have with musical skills.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni, K. 527 (arr. for wind ensemble) – Act I Scene 5: Aria: Madamina, il catalogo e questo (Zurich Wind Octet)

Bizet’s Carmen as arranged for chamber ensemble has a certain snappy brightness that the orchestral version lacks.

Carmen, 2023 (Chicago Summer Opera)

Georges Bizet: Carmen (arr. A. Tarkmann) – Act I: Overture – Prelude (Arte Ensemble)

Operas were one case where playing music at home could tell you so much about the work, but the lack of singers removed one important dimension from the performance.

In the case of symphonies, as we saw above with the Mendelssohn overture, the thinness of the ensemble sound could bring out other hidden parts of the music.

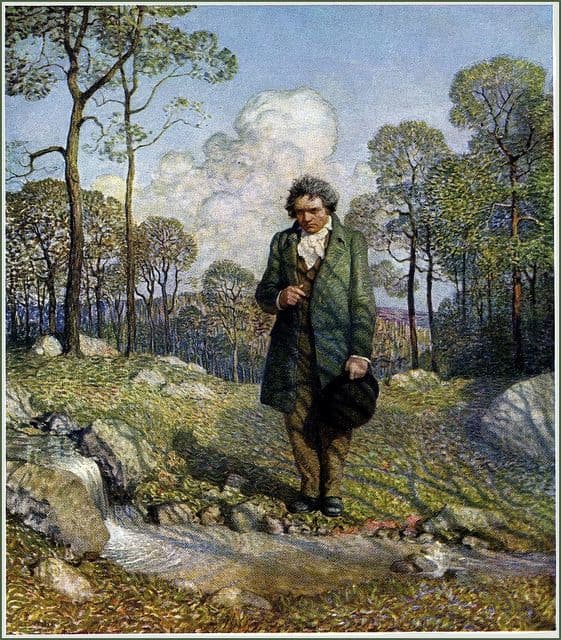

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6, well-known for its evocation of the world of nature, works well in a smaller version.

N.C. Wyeth: Beethoven and Nature, 1921

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68, “Pastoral” – I. Pleasant, cheerful feelings aroused on approaching the countryside: Allegro ma non troppo (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Norrington, Roger cond.)

Here, Mozart’s student Johann Nepomuk Hummel arranged Beethoven’s symphony for flute and piano trio. He made arrangements of all of Beethoven’s symphonies between 1825 and 1835, after Beethoven’s death. Although Hummel and Beethoven’s initial relationship was very bad (Hummel and Beethoven went after the same woman, and Hummel won the heart of Elisabeth Röckel), Beethoven eventually recognized Hummel’s value – they were both friends with the writer Goethe, and Beethoven recognized Hummel’s excellence as a pianist.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68, “Pastoral” (arr. J.N. Hummel for flute and piano trio) – I. Pleasant, cheerful feelings aroused on approaching the countryside: Allegro ma non troppo (Pettman Ensemble)

Home music making drove the arrangements industry and, at the same time, spread composer’s works into places that did not have access to a concert hall or an opera theatre. We may not regard them as much today, with so many of the full orchestral versions available to us, but they can bring much knowledge of a composer’s style, a composer’s technique and sound, and so much more to the listener.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter