In a previous blog entitled “Beethoven (Concert) Overtures,” we examined the eleven overtures that Beethoven wrote for a variety of occasions and under different circumstances. We noted that the four overtures for various performances and versions of his opera Leonore/Fidelio and the overture to Coriolan, originally attached to a play, developed a life of their own in the concert hall. We still don’t know if the independent concert overture was the result of Beethoven’s intentions or a mere byproduct of the composer’s growing popularity. We do know, however, that these works strongly influenced a number of composers working in the 19th century and beyond. Hector Berlioz, for example, composed a number of overtures destined for the concert hall. However, at least in his initial conception, the concert overture was never entirely distinct from its dramatic cousin, as Berlioz was never overly concerned with specific genre designations. Berlioz’s concise and highly popular one-movement works raise questions regarding the effect of story or program upon pure musical coherence, as they were subject to a greater or lesser degree of literary influence. Such is certainly the case with Berlioz’s Waverley Overture, which takes its inspiration from Sir Walter Scott’s first novel, published anonymously in 1814.

Hector Berlioz: Waverley Overture

Hector Berlioz’s Waverley Overture

Hector Berlioz: Waverley Overture, Op. 1 (South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden and Freiburg; Sylvain Cambreling, cond.)

The novel, which sprang from Scott’s childhood recollections and his desire to preserve in writing the features of life in the Highlands and Lowlands of Scotland, tells the story of a romantic young man during the Jacobite rebellion of 1745. The colorful, heroic and brutal values of Scotland’s past are juxtaposed with more orderly, sane and prosperous but duller attitudes of the emerging present. The Overture to Waverley was composed in 1827 and first performed at a concert at the Conservatoire on 26 May 1828, the first orchestral concert to be given by Berlioz and one devoted wholly to his own music. This work, to which Berlioz finally affixed the label Opus 1, is a fitting designation for his first independent orchestral work that does not rely on previously composed music. The musical score is prefaced by a quotation from the novel and reads, “Dreams of love and ladies’ charms give way to honour and to arms.” This inscription clearly refers to the musical contrast between the slow and lyrical introduction with its broad theme for the cellos and the brilliant allegro that follows.

Richard Wagner: Concert Overture No. 2 in C Major

Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient

Richard Wagner: Concert Overture No. 2 in C Major (Leipzig MDR Symphony Orchestra; Jun Märkl, cond.)

At the tender age of 13, Richard Wagner accompanied his mother on a journey to the city of Prague. The vibrant cultural and artistic environment immediately fascinated young Richard; however, once they arrived, they heard the news of Beethoven’s death.

Richard records in his autobiography, “Obsessed as I still was by the terrible grief caused by Weber‘s death, this fresh loss, due to the decease of this great master of melody, who had only just entered my life, filled me with strange anguish. It was now Beethoven’s music that I longed to know more thoroughly.” In April 1829, he saw the esteemed operatic soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, whose unique vocal timbre combined with dramatic intensity of expression, in the role of “Leonore” in Beethoven’s Fidelio. Of course, young Richard became immediately infatuated with Schröder-Devrient and would subsequently write a number of operatic roles for her. At this stage of his musical development, however, he was most interested in the “Overture,” which affected him deeply. Young Richard reports, “The direct result of this performance was my intense longing to compose something that would give me a similar feeling of satisfaction.” He composed an overture connected to a dedicated theatrical play and two concert overtures, the second in C major modeled after Beethoven’s Egmont.

Felix Mendelssohn: The Hebrides Overture, Op. 26

Mendelssohn’s “Hebrides Overture” does resemble an operatic overture, but it was always intended for concert performance rather than as a prelude to a theatrical work. Mendelssohn and his childhood friend Carl Klingemann visited Scotland in 1829. They wandered around the lakes and moors of the Scottish Highlands, including the Hebrides islands off the west coast of Scotland.

Entrance to Fingal’s Cave, 2004

Mendelssohn wrote many colourful letters about their adventures, “describing the comfortless, inhospitable solitude that stood in contrast to the entrancing beauty and wildness of the countryside.” While on a ferry voyage in western Scotland, Mendelssohn was so struck by the misty scene and the crashing waves that a melody came into his mind, “a melody with all the surge and power of the sea itself.” As he wrote to his sister Fanny, “In order to have you understand how extraordinarily the Hebrides affect me, the following came to my mind.” And that postcard contained the opening phrase of what would eventually become his Hebrides Overture. It has been suggested that the echoes Mendelssohn experienced in Fingal’s Cave inspired this particular theme, although there is no definitive proof that Mendelssohn ever got close enough.

Robert Schumann: Julius Caesar Overture, Op. 128

Vincenzo Camuccini: The Death of Julius Caesar

Robert Schumann: Julius Caesar Overture, Op. 128 (London Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

On 17 January 1851 Clara Schumann noted in her diary, “Robert is working incessantly. Now, he is writing an overture for Julius Caesar. He was so enthused by the idea of writing overtures to several of the most beautiful tragedies that his genius once again is bursting with music.” For Schumann, the question of whether an overture should be an autonomous work or serve as a prelude to a play was left open, as he avoided strict boundaries. “After reading the respective literary work, he summarised his impression of the character and atmosphere of the dramatic material for the first time, irrespective of whether the overture was intended to offer an image of the entire work or simply introduce.” For each overture, “Schumann determined anew the relationship between plot formation and the transit function with regard to the literary piece.” On the score of his Julius Caesar Overture, Schumann referenced all the important stages of the drama, visualising them as musical reference points. As such, “the overture treats the heroic in its solemnly majestic and hopeful, mobilising manner both as a funeral march and as a restrained festive march along with appropriate fanfares, interspersed with chorale-like fragments. Thus, a musical form is developed and presented in its inherent contrasting tendencies.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: 1812 Overture

While Schumann’s Julius Caesar Overture has found only limited traction in concert halls, Tchaikovsky’s festival overture The Year 1812 is among the best known and most frequently performed of the composer’s work. Composed and orchestrated between September and November 1880, it was commissioned for the opening concert of the All-Russian Arts and Industrial Exhibition. Scheduled to take place in 1881 in Moscow, it commemorates Russia’s defeat of Napoleon in 1812. Actually, Nikolay Rubinstein, appointed head of the music section for the exhibition, gave Tchaikovsky three options. First, he could write an overture to open the exhibition or compose an overture for the Silver Jubilee of Alexander II. The final option was a cantata for the consecration of the nearly completed Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, which was built to commemorate Napoleon’s defeat in 1812. In his first reply, Tchaikovsky expressed his “utmost loathing” for such commissions. He writes, “it is impossible to set about without repugnance such music which is destined for the glorification of something that, in essence, delights me not at all. Neither in the jubilee of the high-ranking person (who has always been fairly antipathetic to me), nor in the Cathedral, which again I don’t like at all, is there anything that could stir my inspiration.” In the event, he did find inspiration and wrote in 1882, “ I am undecided as to whether my overture is good or bad, but it is probably, without any false modesty, the latter.”

Johannes Brahms: Tragic Overture, Op. 81

The programmatic background for Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture is well established, but things are, as usual, rather more slippery with the Tragic Overture, Op. 81 by Johannes Brahms. We do know that it was composed while on a summer holiday in 1880, but even Brahms wasn’t sure whether to call it “Tragic or Dramatic, or something else.” Commentators have debated at length whether it was intended for a specific tragedy, namely as a prelude to a new production of Goethe’s Faust. This seems entirely out of character for Brahms, but it probably arose because Brahms wrote to a friend, “I could not refuse my melancholy nature the satisfaction of composing an overture to a tragedy.” However, Brahms also asserted that “it was not connected to any particular narrative.” It might be significant that Brahms frequently sketched and completed major works in pairs, such as the first two symphonies. As such, the Tragic Overture is actually the companion piece of the Academic Festival Overture, a work composed in tribute to the University of Breslau, an institution that awarded him an honorary doctorate in philosophy. This boisterous potpourri of student drinking songs stands in marked contrast to the dark and moody Tragic Overture. Both overtures sounded in early January 1881 at the University of Breslau, and critics reported that the “effect of the Tragic Overture on the audience was so profound that it detracted from the gaiety of the other.” As Brahms put it, “one weeps while the other laughs.”

Antonin Dvořák: Othello Overture

In 1874, Antonin Dvořák submitted an application for an artist’s stipend from the Austrian government for poor but talented students. The head of the selection committee was a close personal friend of Johannes Brahms, the highly influential Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick. According to the committee, Dvořák’s works “display undoubted talent, but in a way which remains formless and unbridled.” This somewhat ambiguous endorsement, nevertheless, was sufficient to bequeath Dvořák the highest available stipend, and it set the composer on a path to international recognition. Yet it also brought severe condemnation at home, and eventually, it came down to a question of identity. After a period of deliberation, Dvořák concluded that he always was, and always would be, a simple country composer from Bohemia. As a result, his aesthetic conception and his musical language changed; it became more outspoken, more deliberate, more descriptive and more topical.

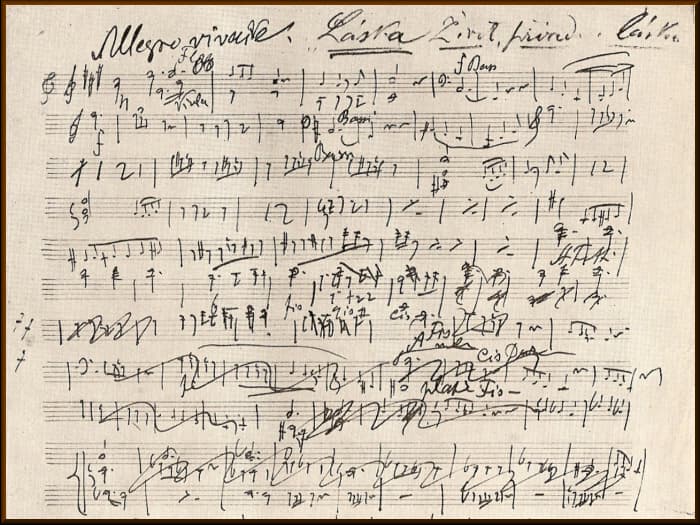

Antonin Dvořák’s Othello Overture

A trilogy of concert overtures, among them the Othello Overture based on the Shakespearean play, beautifully reflects Dvořák’s new musical direction. A hymn-like slow introduction presents two distinctive musical thoughts. One is the sombre theme associated with Othello, which is contrasted by a jagged and sinister musical metaphor for jealousy. The “Allegro” proper incessantly grows in intensity as Othello’s jealousy is balanced by more lyrical music indicative of Desdemona’s love. Musical quotations from Wagner’s Die Walküre and his own Requiem signal the end of this tragic tale. In an exceedingly violent musical outburst, Othello commits suicide after killing his wife.

William Walton: Johannesburg Festival Overture

The South African city of Johannesburg was established in 1886 for one reason. Gold was discovered on a farm owned by Jan Gerrise Bantjes in 1884. In fact, it was part of an extremely large gold deposit found along an area known as the “Witwatersrand.” Nobody really knows how the city got its name, but within ten years, Johannesburg counted 100,000 people. When the city celebrated its seventieth anniversary in 1956, William Walton set to work and composed a fast-paced and fun overture packed with vitality and verve that should, as the commission specified, include “African themes.”

Origin of Johannesburg where gold was first found

Since Walton had never been to Africa, he requested recordings of traditional African music from the African Music Society, and the main theme in this concert overture takes its inspiration from a piece called “Masanga,” composed by the Congolese composer Jean-Bosco Mwenda. You might also notice the complex African rhythms performed by three percussionists on eleven instruments. Of course, this is a portrait of an African city in “English guise, fit music for an English Commonwealth Nation.”

Sergei Prokofiev: Overture on Hebrew Themes, Op. 34

Sergei Prokofiev openly welcomed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and initially contemplated adding his revolutionary musical voice to the political and social expressions of Russian dissent. However, once he had sought permission to go abroad, he managed to secure an exit visa from the People’s Commissar of Public Education and arrived in New York in the fall of 1918. Determined to focus exclusively on interpreting his own compositions, he initially declined a 1919 commission from the Jewish émigré ensemble Zimro. The ensemble, collecting funds for the creation of a music conservatory in Jerusalem, was looking for a repertory that would support the unusual instrumentation—String Quartet, Piano and Clarinet—of their musical group. Eventually, the composer relented, and the Overture on Hebrew Themes premiered with Prokofiev at the piano on January 20, 1920. This single-movement composition utilises two contrasting yet complimentary musical themes. A rhythmically lively first melody sounded in the clarinet and emerged after an introductory rhythmic ostinato. The rhapsodic second theme, showcasing the String Quartet and the Piano, unfolds in undulating mournful lines.

Prokofiev described his two-year tenure in America as a gradual process of failure; however, he did arrange this work for orchestra in 1934.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter