Composer Richard Wagner was born in Leipzig in 1813. He became arguably the greatest opera composer of all time.

Here are some tidbits about his life and career:

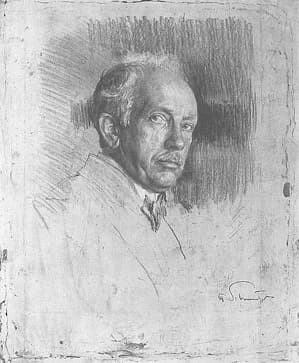

Richard Wagner, 1860

- Wagner’s reputation rests almost entirely on his operas.

- Wagner advocated for a genre known as the “Gesamtkunstwerk”, or “total work of art.”

- In a Gesamtkunstwerk, all aspects of a music drama – script, story, visuals, and music – are mixed together to create one powerful cohesive whole.

Wagner took his own advice to heart and wrote all of his own librettos (i.e., scripts and stories). He often took inspiration from cultural mythology. - Wagner had an affair with composer Franz Liszt’s daughter Cosima. Eventually, he married her. Their children went on to lead a festival that he founded called the Bayreuth Festival, whose goal is to promote the work of Wagner. The Bayreuth Festival still happens today.

- Wagner was extremely interested in politics. He became involved in revolutionary causes and was even pursued by the authorities for revolutionary activities in the 1840s and 1850s.

- His often offensive and anti-Semitic writings are important aspects of his legacy and can’t be swept under the rug. Unsurprisingly, the Nazis were major fans of his work, even though he died decades before they came to power. This link has left a sour taste in the mouths of many music lovers.

- Wagner was one of the most influential figures of the nineteenth century, and not just musically. There’s even a whole big book devoted to charting his social, cultural, and political influence called Wagnerism.

As you can imagine, Wagner’s massive music dramas don’t fit well in a listicle-type article like this. But we’re going to try our best!

If these excerpts intrigue you, make sure to check out works in their entirety. None of these excerpts are going to give a full picture of Wagner’s art just by themselves.

Rienzi (1838-1840)

Rienzi was Wagner’s third opera but his first success. He was twenty-nine years old when it was premiered.

Its title character is the real-life Cola di Rienzo, an Italian politician who lived in the fourteenth century. He championed the unification of Italy, among other reforms.

Nineteenth-century German reformers who were pushing for liberal nationalist causes of their own were inspired by his example. Wagner would become very involved in that liberalization movement.

Wagner hoped Rienzi would be premiered at a prestigious opera house. Unfortunately, he was imprisoned in a debtors’ prison at the time.

That said, two years later, Wagner’s tireless networking did ultimately lead to opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer mounting a production of Rienzi in Dresden. This was one of Wagner’s first big breaks.

Legend has it that Rienzi influenced Hitler to go into politics.

Tannhäuser (1845)

Tannhäuser was a bardlike figure from medieval German history. Wagner wrote a version of him into this opera.

In this opera, Tannhäuser lives in a kind of fairyland known as Venusberg, which is full of sexy nymphs. However, Tannhäuser is tired of the culture there. To Venus’s displeasure, he asks to leave this paradise of sensuality.

He departs and meets up with a woman named Elisabeth, who has been in love with him for a long time. He’s cagey about where he has been.

Meanwhile, a contest is announced: the poet who can best explain love can have Elisabeth’s hand in marriage. While he’s competing, Tannhäuser gives away a little too much about what he knows of the pleasures of love, and everyone realizes that he has visited Venusberg.

Chastened, he goes to Rome to seek forgiveness from the Pope. Unfortunately, the Pope does not grant him forgiveness.

Other German pilgrims return, but a devastated Tannhäuser tries to return to Venus and the sexy nymphs, not knowing where else to go.

Then, in what’s viewed as a miracle, Elisabeth dies. Her death provides a kind of salvation to Tannhäuser, and he dies, too, forgiven.

Lohengrin (1845-1848)

Lohengrin revolves around the tale of a knight named (spoiler alert) Lohengrin.

In the opera, Lohengrin arrives in a boat drawn by a swan to rescue Elsa of Brabant, who has been falsely accused of murdering her brother.

Lohengrin agrees to defend Elsa under the condition that she never asks his name or about his origin.

Despite this odd request, the two fall in love and marry. Of course, Elsa’s curiosity ultimately gets the better of her, and she breaks the vow, leading to Lohengrin’s departure.

Elsa then dies of grief.

Das Rheingold (1853-1854)

By the mid-1850s, massive operas on their own weren’t enough to satiate Wagner’s ambition. He envisioned something even bigger: an entire cycle of operas to be performed on successive nights. Think of the project as a nineteenth-century Lord of the Rings.

Das Rheingold (literally, The Rhine Gold, a reference to the mythical gold said to be in the Rhine River) was his first entry in the series.

It tells the story of how the dwarf Alberich renounces love to steal the Rhine gold and forge a powerful ring that grants him dominion over the world.

The gods, led by Wotan, seek to obtain the ring to secure their reign in Valhalla.

The opera sets the stage for the ensuing power struggles, greed, and epic conflicts that unfold throughout the rest of the Ring cycle.

Die Walküre (1854-1856)

Die Walküre is the second entry in the so-called Ring Cycle. It centers around the forbidden love between the twins Siegmund and Sieglinde, who were separated in childhood.

Siegmund, son of the chief god Wotan, falls in love with Sieglinde, who is trapped in a forced marriage. Siegmund claims Sieglinde as his wife. Sieglinde’s betrayed husband is outraged and sets up a duel with Siegmund for the following day.

Wotan tells his daughter, the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, that she should intervene on the side of Siegmund. However, Wotan then talks with his wife, the goddess of marriage, who reminds him that he should not intervene to promote adultery. So Wotan changes his mind.

But Brünnhilde decides to stick with Wotan’s original plan and to aid Siegmund. Unfortunately, as soon as Siegmund is on the verge of winning the fight, Wotan intervenes so that Siegmund loses and is killed. Brünnhilde flees with Sieglinde.

In the grief of their exile, Brünnhilde shares great news: Sieglinde is pregnant with Siegmund’s baby. Wotan catches up with the two women and punishes them by making Brünnhilde mortal and exiling Sieglinde behind a wall of flames.

The most famous excerpt from Die Walküre is likely the Ride of the Valkyries, which has entered pop culture after many appearances in films and commercials, albeit divorced from its original context.

Tristan und Isolde (1857-1859)

The Ring Cycle was, as you can imagine, an overwhelming project to work on, so Wagner took a break for a while to focus on composing Tristan und Isolde.

For this new opera, Wagner continued taking inspiration from myths and legends, this time borrowing from the Celts.

He tells the tragic love story of Tristan, a brave knight in charge of guarding Isolde, an Irish princess. Isolde is being sent on a ship to Ireland to marry Tristan’s uncle, a king whom she does not love.

Isolde wants to drink poison to escape, but her maid creates a love potion instead. While on the ship, Tristan and Isolde drink it and fall hopelessly in love.

Later, when the king leaves the castle on a hunting trip, Tristan and Isolde have a tryst. They’re discovered, and a loyalist stabs Tristan.

The wounded Tristan is taken back to his own castle, where he dies. Isolde arrives and decides she cannot live on, and kills herself in a powerful and transcendent death scene.

Wagner created a condensed version of the opera with his “Prelude and Liebestod” or “Prelude and Love Death”, which consists of both the beginning and the end of the opera.

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1862-1868)

Not only did Wagner press pause on the Ring Cycle to write an opera about forbidden love, he also spent some of that time falling in love with Franz Liszt’s married and much younger daughter, Cosima.

Richard and Cosima did not die a la Tristan and Isolde. Instead, they took a vacation together in 1864. Nine months later, she gave birth to a daughter, who they named Isolde.

During this personally tumultuous time, Wagner composed a comic opera called Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. (It feels important to mention that Cosima’s husband Hans von Bülow conducted the premiere of this opera in 1868, which was supremely awkward all around.)

In Die Meistersinger, Wagner returned to a historic German setting, but this time he discarded the supernatural or mythological elements he often used.

The opera is set in the sixteenth-century in Nuremberg and centers around the guild of Meistersinger, a group of skilled amateur poets and musicians who compete in song contests.

The opera gets rather meta as the characters discuss the value of cutting-edge art and what creators’ relationships should be to everything that came before: a question that continually haunted Wagner and his contemporaries.

He also, very cheekily, adds a reference to his own work when a character says, “My child, I know a sad tale of Tristan and Isolde.” (Again, I’ll remind you, this opera was conducted by Cosima’s husband, who was raising Wagner’s daughter Isolde as his own.)

Siegfried (1856-1871)

Hans von Bülow was not stupid, and he understood what was happening. In 1869, after Richard and Cosima had their third child together, he finally acknowledged his marriage was over, writing to her, “You have preferred to consecrate the treasures of your heart and mind to a higher being: far from censuring you for this step, I approve of it.” Cosima was divorced and married to Wagner in the summer of 1870.

That personal drama mainly settled, it was time to return to the Ring Cycle in earnest (especially since their youngest son was named Siegfried, after the in-progress opera).

Siegfried continues the epic saga of gods, heroes, and mythical creatures. Its hero is both fearless and naive. In the operatic crossover event of the century, he is the son of the twins Siegmund and Sieglinde, the main protagonists from the previous Ring Cycle entry “Die Walküre.”

Raised in the wilderness by the shapeshifting dwarf Mime, Siegfried embarks on a journey to discover his true identity and destiny. He forges the magical sword Nothung and slays the dragon Fafner, and, in a nice bonus, gains the ability to understand the language of birds.

With courage, Siegfried sets out to rescue the sleeping Valkyrie, Brünnhilde, the one surrounded by a wall of fire on a mountaintop. Of course, they then fall in love.

Götterdämmerung (1876)

After Wagner spent multiple operas fleshing out his story, the stage was set for an epic conclusion. If Wagner could pull a fourth Ring Cycle opera off, he’d succeed in creating something the world had never seen before.

He delivered.

The final opera of the cycle portrays the catastrophic downfall of the gods and the destruction of the divine realm, Valhalla. It follows the intertwining destinies of Siegfried, Brünnhilde, a villain named Hagen, and various mythical figures.

The story also revolves around the quest for the ring of power that had been introduced in Das Rheingold, which leads to betrayal, war, and ultimate devastation.

By the end of the story, Siegfried is killed, but Brünnhilde lights a fire around his body. This fire eventually causes the Rhine River to flood, which enables the Rhinemaidens to steal back the magic ring. The fire burns Valhalla and ends the age of the gods, marking the beginning of a new era.

It almost feels as if Wagner, in his maturity, was somehow intuiting the destruction that would be brought about by the various wars and upheavals of the twentieth century.

Parsifal (1877-1882)

Parsifal was Wagner’s last opera. It was premiered in 1882. He wrote it specifically for a music festival in Bayreuth, Germany that he had meticulously curated for the promotion of his own works. It was his dream that Parsifal would only be performed in Bayreuth; however, nowadays, it can be seen all over the world.

For this outing, he couldn’t resist dipping again into history and mythology. This time, he added even more mysticism than usual.

King Amfortas has an incurable wound after being betrayed by a woman during a fight. He has been told by a prophet to await a “pure fool” who will change his life.

A swan is shot with a bow and arrow and falls to the ground. There is a search for the hunter. He is found; he is a young man; and his name is Parsifal.

Three acts’s worth of religiously tinged drama then unfolds, but in the end, Parsifal is revealed to be the chosen one to restore the Holy Grail’s power and to heal Amfortas.

Conclusion

Wagner’s grave

Wagner’s health deteriorated greatly during the composition of Parsifal. By the time it was premiered in May 1882, he was very ill, but at the end of the final performance of a sixteen-performance run, he snuck into the orchestra pit to conduct the final act.

Afterward, the Wagners traveled to Italy to recuperate. Unfortunately, Wagner’s health never improved. He died of a heart attack in February 1883.

Cosima, obsessed with him until the end, was completely devastated, going so far as to lay on his coffin before it was buried. Her children had to pull her away.

Eventually she found the strength to take over the Bayreuth Festival. She was in charge for twenty-two more years. She helped to solidify Wagner’s legacy, and her children became involved in that obsession, too.

Cosima Wagner died in 1930 – ominously, not long before Wagner-loving Nazis seized control of Germany. The couple’s legacy would be forever tied up with politics she never had a chance to witness.

For more about Wagner, check out our Wagner tag.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter