The young Poulenc

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) was one of the most original and sincere voices of the 20th century. His music and personality mirror the often-conflicting nature of humanity. Simultaneously earthy and refined, a promiscuous homosexual who fathered a daughter late in his life, he was a modern urbane composer who was unafraid to indulge his urges for nostalgia and for mystic spirituality.

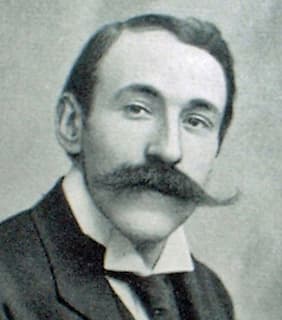

Poulenc, 1922

Darius Milhaud suggested, “Francis Poulenc is music himself, I do not know of any other more direct music, expressed in a simpler way that goes straighter to the target.” Poulenc’s musical language speaks clearly, directly, and humanely to every generation; it is music that can move you to both laughter and tears within seconds. Poulenc was born on 7 January 1899 in the 8th arrondissement of Paris. His father Émile Poulenc was director of a family pharmaceutical business, which eventually became the pharmaceutical giant “Rhône-Poulenc.” He was a pious and deeply religious Catholic whose musical interests primarily focused on Beethoven. His mother Jenny, née Royer, came from a long line of Parisian artists and craftsmen. Poulenc regarded this parental heredity as the key to his musical personality. “He associated his deep Catholic faith with his Aveyronais roots and attributed his artistic heritage to his mother’s family.”

Francis Poulenc: Rapsodie nègre Op. 1

Ricardo Viñes

Poulenc’s mother was a capable pianist, and inspired what he called “a lifelong taste for adorable bad music.” Francis started piano lessons at the age of five, and he quickly became fascinated by the music of Debussy, Schubert, and Stravinsky. A career in music was decidedly on the horizon, however, his father first insisted on a conventional classical education at the Lycée Condorcet. World War I upset all plans, and Poulenc’s mother died when he was 16 and his father when he was 18. His childhood friend Raymonde Linossier, the future lawyer and orientalist, introduced Poulenc to Adrienne Monnier’s bookshop in the rue de l’Odéon. It was the famed meeting place for the avant-garde poets Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Paul Éluard and Louis Aragon, and Poulence eventually set many of their poems to music. He also became a student of pianist Ricardo Viñes, and through him made the acquaintance of other notable musicians, including Auric, Satie, and Falla.

Francis Poulenc: Le Bestiaire

Les Six

Confronted with the death of his parents, Viñes “was far more than a teacher; he was a spiritual mentor and the dedicatee or first performer of his earliest works.” Poulenc described Viñes as “a most delightful man, a bizarre hidalgo with enormous moustachios, a flat-brimmed sombrero in the purest Spanish style, and button boots which he used to rap my shins when I didn’t change the pedalling enough… I admired him madly, because, at this time, in 1914, he was the only virtuoso who played Debussy and Ravel. That meeting with Viñes was paramount in my life: I owe him everything … In reality it is to Viñes that I owe my fledgling efforts in music and everything I know about the piano.” Poulenc had been composing all along, but he self-consciously destroyed his first attempts. His début as a composer took place in 1917 at the Théâtre du Vieux Colombier at an avant-garde concert organized by Jane Bathori. In due course, his works were often performed in the concerts given at the studio of the painter Emile Lejeune, in the rue Huyghens in Montparnasse. These concerts also featured music by Milhaud, Auric, Honegger, Tailleferre and Durey, and the experimental and loose group of composers christened “Les Six” took their musical bearings from the music hall, the cabaret and the circus.

Francis Poulenc: Trois mouvements perpétuels (Pascal Rogé, piano)

Jacques Emile Blanche: Le Groupe des Six

Poulenc was essentially self-taught as a composer, as his only attempt to study at the Paris Conservatoire was rejected as follows: “Your composition stinks, it is inept, infamous balls… Ah! I see you’re a follower of Stravinsky and the Satie gang. Well, goodbye!” Throughout his life, Poulenc was conscious of his lack of academic musical training. Ravel advised him to take composition lessons, and Milhaud suggested the composer and teacher Charles Koechlin. Poulenc did approach Koechlin in 1921 and asked for lessons, because he had “obeyed the dictates of instinct rather than intelligence.” The lessons intermittently continued for about four years, but “the composer was lucky that public mood was turning against late-romantic lushness in favor of the freshness and insouciant charm, technically unsophisticated though they were.” The delicious and instinctive flavor of Poulenc’s music was described as follows. “Take Chopin‘s dominant sevenths, Ravel’s major sevenths, Fauré‘s plain triads, Debussy’s minor ninths, Mussorgsky‘s augmented fourths. Filter these through Satie by way of the added sixth chords of vaudeville, and blend in a Bohemian way.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Francis Poulenc: Les Biches