We’ve all been there: liking somebody more than they like us. Experiencing unrequited love is horribly painful.

It might be cold comfort, but the good news is that classical composers have been deeply inspired by unrequited love of all kinds…so there’s no need to feel alone!

Today, we’re looking at ten pieces of classical music that explore the emotions of loving someone who doesn’t love you back.

© Andrii Yalanskyi

John Dowland: Disdain Me Still from A Pilgrimes Solace (1612)

A Pilgrimes Solace is a book of twenty-one songs for voice, lute, and viol. It was composed by English composer John Dowland in 1612, the same year that he was named as a lutenist in James I’s court.

The melancholy “Disdain Me Still” includes the following heartbreaking lyric (updated to more modern English for readability):

And though you frown, I’ll say you are most fair:

And still I’ll love, though still I must despair.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin (1823)

Die schöne Müllerin (“The Fair Maid of the Mill”) is a song cycle consisting of twenty songs.

They tell the story of a journeyman miller who follows a brook through the countryside, stumbles upon a mill and falls in love with the miller’s daughter.

However, he is too professionally inexperienced to be a suitable marriage candidate, and the young woman is uninterested in him. The songs trace his ensuing emotional breakdown.

By the final song in the cycle, the young man is nowhere to be found, and the voice narrating switches from the young man to the brook itself, who ominously tells the young man, “Rest well, rest well, close your eyes. Wanderer, you weary one, you are at home.”

Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique (1830)

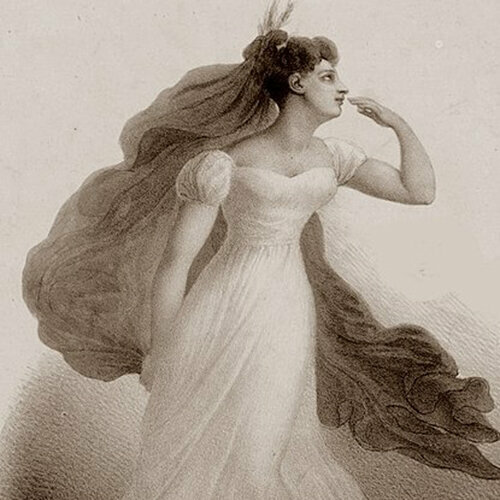

In 1827, a 24-year-old Hector Berlioz attended an English-language performance of Hamlet and fell in love with the actress who played Ophelia, an Irish woman named Harriet Smithson.

Of course, this love was based more on lust and delusion than anything truly real. Smithson didn’t even speak French, and Berlioz didn’t speak English! Nevertheless, he sent her multiple love letters, all of which went unanswered. Smithson left Paris in 1829.

Harriet Smithson as Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet

To channel his obsessive thoughts, Berlioz came up with a terrifying scenario for a symphony.

It follows the emotional journey of a young genius artist who falls in love with his ideal of a woman. He is reminded of her everywhere, from lively ballroom dances to countryside sojourns, and he goes mad from not being able to escape her memory.

Finally, to dull the obsession, he takes opium. In his drug-fueled haze, he dreams that he has killed his love and been sentenced to death. After his death, he attends a witches’ Sabbath, a gathering of “shades, sorcerers and monsters of every kind”, according to Berlioz’s own program notes. His beloved appears in the form of a witch, taunting him.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet No. 3 (1875)

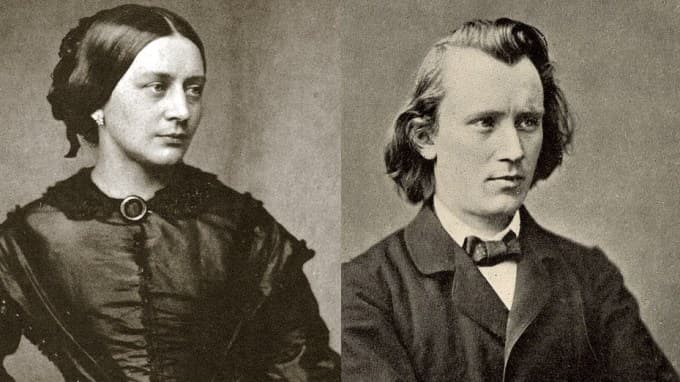

When he was twenty years old, aspiring composer Johannes Brahms met 43-year-old critic and composer Robert Schumann and his 34-year-old wife, internationally renowned pianist Clara Schumann.

He struck up a deeply meaningful friendship with the couple. And as Robert’s mental health deteriorated, Brahms began falling in love with Clara.

Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms

The two would never marry, even after Robert died, but they stayed dear friends and were artistic soulmates for the rest of their long lives.

In the 1870s, Brahms began working on a piano quartet, using some material from the early days of his relationship with the Schumanns.

He wrote to his publisher about the work, “On the cover, you must have a picture, namely a head with a pistol to it. Now you can form some conception of the music! I’ll send you my photograph for the purpose. You can use the blue coat, yellow breeches, and top boots since you seem to like colour-printing.”

Brahms is referring to Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, in which an artist named Werther falls in love with an engaged woman who cares deeply for him but is not in a position to return his love. As you can imagine, the story ends in tragic suicide. Luckily for us, Brahms wrote this beautiful music instead of taking out a revolver.

Gabriel Fauré: Élégie for cello (1880)

In July 1877, composer Gabriel Fauré proposed to a woman named Marianne Viardot.

Marianne was musical royalty: she was the daughter of one of the era’s most extraordinary musicians, a singer and composer named Pauline Viardot.

She was a fine singer herself (one of her fans was none other than Clara Schumann), and it’s easy to imagine the gifted couple bonding over music.

However, just a few months after she said yes, Marianne broke off the engagement. Fauré was devastated. According to legend, this Élégie explores some of the emotions he endured during this time.

In 1883, he married a woman he never loved. Around the same time, his music started becoming more introverted and elusive, with the dramatic overt passion of the Élégie rarely appearing again in his work.

Gustav Mahler: Songs of a Wayfarer (1884-85)

When Gustav Mahler was a young conductor working at an opera house in Kassel, Germany, he met a soprano named Johanna Richter. He fell in love with her, but it’s unclear if she fully returned his affections.

On New Year’s Eve in 1888, the two attended what sounds like the worst New Year’s party in music history. Mahler wrote to a friend:

I spent yesterday evening alone with her, both of us silently awaiting the arrival of the new year. Her thoughts did not linger over the present, and when the clock struck midnight and tears gushed from her eyes, I felt terrible that I was not allowed to dry them. She went into the adjacent room and stood for a moment in silence at the window, and when she returned, silently weeping, a sense of inexpressible anguish had arisen between us like an everlasting partition wall, and there was nothing I could do but press her hand and leave. As I came outside, the bells were ringing and the solemn chorale could be heard from the tower.

That year he channeled his emotions into a set of four songs that became known as Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, or “Songs of a Wayfarer.”

The first one’s lyrics begin:

When my love has her wedding-day,

Her joyous wedding-day,

I have my day of mourning!

Fritz Kreisler: Liebesleid (ca. 1905)

Liebesleid (“Love’s Sorrow”) was composed sometime before 1905 as part of Kreisler’s set of three Alt-Wiener Tanzweisen, or “Old Viennese Melodies.”

Kreisler had a habit of composing works but attributing them to other composers. He did this with Liebesleid for a while, claiming that it was the work of old Viennese waltz composer Joseph Lanner, but eventually, the truth came out.

Learn more about Kreisler’s deceptions.

Without lyrics or a specific program, it’s difficult to know exactly what the sorrows referenced in the title are, but it could easily apply to wistful unrequited love.

Alexander Zemlinsky: Lyric Symphony (1922-23)

In 1922, composer Alexander Zemlinsky wrote to his publisher, “I have written something this summer like Das Lied von der Erde. I do not have a title for it yet. It has seven related songs for baritone, soprano, and orchestra, performed without pause. I am now working on the orchestration.”

The sixth song describes loneliness:

Whom do I try to clasp in my arms?

Dreams can never be made captive.

My eager hands press emptiness

to my heart and it bruises my breast.

Leoš Janáček: String Quartet No. 2 (1928)

In 1917, when he was 63 years old, composer Leoš Janáček met a married 26-year-old mother of two named Kamila Stösslová.

Kamila Stösslová in 1917

He fell in love with her immediately. He began obsessively writing her letters and composing music inspired by her. Understandably, however, she did not return his love.

Janáček’s second string quartet is subtitled Intimate Letters and is a portrait of their relationship, with Kamila being portrayed by the viola.

The first movement is about their meeting and the unsettling emotions it provoked. The second is a portrait of yearning. The third is a “vision” of Kamila, while the fourth describes Janáček’s fear of his love.

Benjamin Britten: Bugeilio’r Gwenith Gwyn (1976)

In 1976 composer Benjamin Britten composed his Eight Folksong Arrangements.

One of them was an arrangement of the Welsh folksong “Bugeilio’r Gwenith Gwyn” or “Watching the White Wheat.”

It tells the story of a man who vows to continue loving a woman even though she doesn’t return her affection. In Welsh, he sings

While hair adorns this aching brow

Still I will love sincerely,

While ocean rolls its briny flow

Still I will love thee dearly.

Conclusion

No matter what emotion you’re feeling, someone in the history of classical music has probably felt it and composed something exploring it. Obviously, the theme of unrequited love is no exception!

Do you have a favourite story of unrequited love from classical music history? Let us know.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter