In my initial blog on the 10 most beautiful piano quintets in classical music, I featured incredible masterworks for the combination of the string quartet with the piano. This type of scoring essentially started with Robert Schumann, and from around the middle of the 19th century, it became the standard.

Piano Quintet

Around 1850, the string quartet had evolved into the most important chamber music ensemble, and advances in the design of the piano had greatly expanded its power and dynamic range. Composers like Schumann, Brahms, and later Shostakovich took full advantage of the expressive possibilities of these forces in combination.

As a scholar wrote, “the piano quintet became a genre suspended between private and public spheres, alternating between quasi-symphonic and more properly chamber-like elements.” The musical possibilities of these forces in combination include conversational passages between the five instruments and concertante sections with the combined forces of the strings opposing the piano. Countless composers stepped up to that particular challenge, and here comes an additional series of 10 dazzling and awe-inspiring piano quintets.

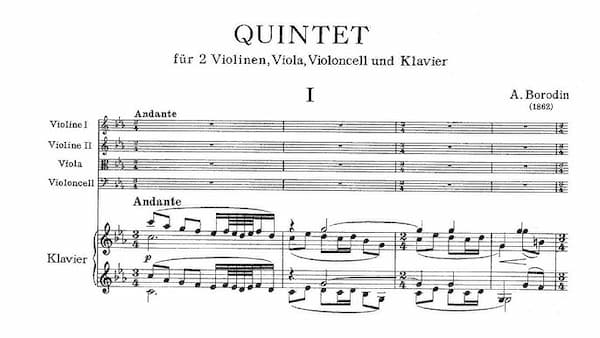

Alexander Borodin: Piano Quintet in C minor

Alexander Borodin (1833-1887) was in the prime of his compositional powers when he embarked on the composition of his quintet in C minor for piano and strings. The inspiration for the work came from Ekaterina Protopopova, an accomplished pianist and fervent admirer of Chopin, Liszt, and above all, Schumann. What is more, she was engaged to Borodin, but suffering from tuberculosis, doctors advised her to move to a warmer climate. As such, Alexander and Ekaterina travelled to Italy in 1861.

We learn from Ekaterina’s diary that Borodin was hard at work on the C-minor piano quintet by May 1862 and that it was completed on 17 July during a short holiday in the seaside town of Viareggio. Borodin had heard Schumann’s piano quintet a year earlier, and he was now ready to outgrow his musical adulation of Mendelssohn.

Borodin’s Piano Quintet

A scholar writes, “Glinka’s influence is once again evident in the melodies and transitions, and the harmonic language is still traditionally tonal. However, the Russian folk element assumes its greatest prominence yet, and the form is much freer.” The traditional formal scheme is completely reversed, as the first movement is rondo-based, a design also used in the “Scherzo.” Taking up almost half of the quintet’s total length, the “Finale” is scored in sonata form. Written before his highly influential meeting with Balakirev, the piano quintet is an original and personal work already pointing towards Borodin’s compositional maturity.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. 14

Already in younger years, Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) complained that there were insufficient opportunities for the performance of French instrumental music. As he later wrote, “The name of a living French composer on a programme made everyone flee.”

Saint-Saëns was an organist at the Eglise de la Madeleine, and he had three symphonies to his name when he embarked on the composition of his piano quintet in A minor, Op. 14. His effort was immediately greeted by rejection and scepticism as French audiences were hostile towards chamber music. As symphonies and chamber music were regarded as the genres of the German-Austrian tradition, these genres were frowned upon as being ‘Germanisme.”

One of Saint-Saëns’ earliest cyclic compositions, the A-minor quintet, dates from 1855, but it was only published ten years later. It is dedicated to this great-aunt Madame Masson née Gayard, who had given him his first piano lessons. The composer wrote a highly virtuoso and dominant piano part, which is often in full opposition to the string quartet. As the work unfolds, however, the strings seem to come more into their own. In the context of French music history, this piano quintet is actually revolutionary.

César Franck: Piano Quintet in F minor

César Franck (1822-1890) was happily married to the actress Madam Félicité Saillot. Yet, she greeted the arrival of her husband’s piano quintet in F minor with public condemnation, fiery scorn and a deeply professed hatred. Given the ferocity of Félicité’s reaction, it is hardly surprising to locate an extra-musical reason for her scorching response. And that reason was a young and beautiful organ student at the Paris Conservatoire by the name of Augusta Holmes.

Franck writes, “Holmes possessed of bold, beautiful features, abundant golden hair, and handsome breasts of which she was justifiably proud.” Frank was not alone in his admiration, as Saint-Saëns and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov were also passionately in love with her. You see, Félicité clearly understood that the pervasive emotionality and infatuation expressed musically was intended for Augusta and not for her.

From the very beginning, we hear Franck’s characteristic restless tonal architecture. A highly expressive slow introduction features a growling bass pedal, with the violin tracing a descending jagged melody. We find great passion and expressive yearning for romantic love, with the “Lento” unfolding as an extended and tender Vocalise between the violin and the piano. The concluding “Allegro non-troppo” is bathed in jittery nervousness and powerful fervour and relies on intensely chromatic harmonic progressions.

Louis Vierne: Piano Quintet, Op. 42

Louis Vierne (1879-1937) had a physically and emotionally challenging life. Born with congenital cataracts in both eyes, he did gain some sight following an operation at the age of seven, but he would remain severely visually impaired. Vierne struggled with politics at the Paris Conservatoire, but in 1900, he became organist at Notre Dame. Six years later, in a rogue street accident, he suffered multiple compound fractures to his left leg, and he had to spend painful years relearning his pedal technique on the organ.

Vierne almost died of typhoid in 1909, and his wife left him for his best friend. It turned out that his much-beloved daughter Colette wasn’t actually his daughter at all, and worst of all, his only son Jacques was killed in action in World War I. Vierne channelled his despair and anguish into his piano quintet, Op. 42. As he wrote, “It is a quintet of vast proportions through every part of which shall flow the spirit of my tender feelings and the tragic destiny of my child.”

Vierne continues, “I shall bring this work to a conclusion with energy as fierce and ferocious as my grief is terrible. I shall produce something of power, of grandeur and strength which shall move fathers to the depths of their hearts with the most profound feelings of love for a dead son. As for me, the last to hold my name, I will bury him with a roar of thunder and not with the plaintiff bleating of a sheep resigned to its happy fate.”

Josef Suk: Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 8

Josef Suk

Josef Suk: Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 8 (Christian Tetzlaff, violin; Florian Donderer, violin; Timothy Ridout, viola; Tanja Tetzlaff, cello; Kiveli Dörken, piano)

The Czech composer and violinist Josef Suk (1874-1935) was a favourite student of Antonín Dvořák, and he even married his daughter Otilie in 1898. A talented violinist, he became a founder-member of one of Europe’s most important string quartets, the Czech Quartet, and his music was admired by Gustav Mahler and Alban Berg. Regarded as the leading composer of the modern Czech school, Suk even had the blessings of Johannes Brahms.

Suk never broke away from the chromatic style of the late 19th century, and the piano quintet in G minor was published in 1915, even though it was composed relatively early in Suk’s career in 1893. It is dedicated to Brahms, and his musical influence is closely felt in the rhetoric of the first movement.

The ”Adagio” is marked “Religioso,” and we hear a chant-like opening in which sweeping arpeggios for the piano are alternated with chords for the strings. The cello takes the lead in a central section, and a pentatonic theme introduces an extended “Scherzo.” There seems to be a musical homage to Dvořák’s piano quintet in the “Trio,” and once again in the “Finale.” It is a youthful and adventurous work but Suk’s harmonic individuality and inventive transformations are already in evidence.

Ernő Dohnányi: Piano Quintet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 1

Ernő Dohnányi

Ernő Dohnányi: Piano Quintet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 1 (Ensemble Raro)

Josef Suk had dedicated his piano quintet to Johannes Brahms, and so did Ernö Dohnányi (1877-1960). Dohnányi started his musical career as a pianist but ventured into composition at the age of eighteen. He studied with Hans Koessler, who, in turn, showed Dohnányi’s Op. 1 to his good friend Johannes Brahms.

Koessler wrote to his young student in 1895, “I have only good news for you. Brahms hates pompous language, but the degree to which he appreciates your talent and achievements may be gathered from the fact that he very much looks forward to hearing you perform the quintet.”

The Op. 1 quintet unfolds in the traditional four movements. The opening “Allegro” presents contracting theme areas, and after a short development, the recapitulation is interrupted by an autumnal adagio passage. The classic “Scherzo” brims with virtuosity and rhythmic inventiveness, while the “Trio” provides a backward glance at Schubert. A somewhat unremarkable “Adagio” is followed by a “Finale” of melodic and rhythmic inventiveness. The music was published by Simrock in Berlin on the recommendation of Brahms.

Charles Villiers Stanford: Piano Quintet in D minor, Op. 25

Charles Villiers Stanford

Charles Villiers Stanford: Piano Quintet in D Minor, Op. 25 (Piers Lane, piano; Vanbrugh Quartet)

By the mid-1880s, Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) had completed three operas, two symphonies, songs, and some highly original church music. He was also the esteemed conductor of the Cambridge University Musical Society and the Bach Choir. Stanford’s most ambitious and grandest chamber work, the piano quintet in D minor, Op. 25, dates from this period.

Joseph Joachim, a regular visitor to Cambridge, was “looking forward to your quintet with great interest.” Only four days later, Stanford confirmed that he had finished the first three movements and that the finale was partially complete. The work was completed in March 1886, and Joachim was able to hear an informal performance at Stanford’s home.

The work unfolds on the ambitious scales of the quintets composed by Schumann and Brahms. Pierre E. Barbier writes, “Stanford conceived his work on a grand scale in which an overarching narrative—the first two movements in minor keys, the last two in major—transported his audience from melancholy introspection to extrovert joy and optimism.”

Arnold Bax: Piano Quintet in G minor

Arnold Bax’s Piano Quintet in G minor

Arnold Bax: Piano Quintet in G minor (David Owen Norris, piano; Mistry String Quartet)

Arnold Bax (1883-1953) was a major creative force on the British music scene, and his piano quintet, one of the first works of his maturity, straddled the outbreak of the First World War. He started the first movement on 16 July 1914, and three days later, the slow movement was finished. The outbreak of the war caused a delay, and the work was not finished until 13 April 1915.

In terms of his output, the quintet marks an emotional and stylistic turning point. Lewis Foreman writes, “Its scale looks forward to the symphonies… and it marks the climax of his early impressionistic period and fully established his mature style.”

For Bax, “the only music that can last is that which is the outcome of one’s emotional reactions to the ultimate realities of Life, Love, and Death. The first movement is certainly passionate and tempestuous, and created around three principle ideas. The main idea of the slow movement is introduced by emphatic string pizzicato chords, and it unfolds as a song without words of lyrical melancholic beauty. In the “Finale”, Bax uses the same three main ideas of the first movement to create a completely different mood. Surprisingly, it also sounds like an “Epilogue,” in which the opening theme is transformed once again before reaching an emotional conclusion.

Amy Beach: Piano Quintet, Op. 67

On the occasion of Amy Beach’s (1867-1944) 75th birthday, a critic wrote, “she has always been a romantic in the best sense of the word—a devotee of beauty and a follower of the gleam. She has not been tempted into impressionism or atonality, nor has she strayed into the jungle of discords. Her music has a timelessness that should make it enduring.” Peter Dickenson added, “Beach needs no special pleading from gender studies to reach an audience, as the current record catalogue abundantly shows.”

Beach was profoundly influenced by the Germany Romantic tradition, and she enhanced her rudimentary composition lessons by tirelessly studying the musical scores of Bach and Brahms. One of her most popular works, the quintet for piano and strings in F-sharp minor had its origins in her public performance of Brahms’s Quintet Op. 34. In fact, she uses the second theme of the last movement as the basis for many of her own. As you can clearly hear, the Brahmsian influence is unmistakable in sound and style, and also in form and harmonic language.

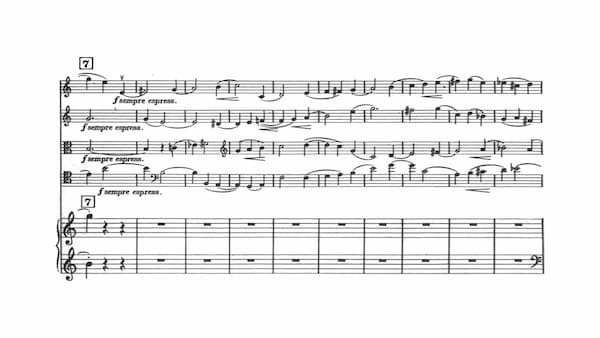

Bohuslav Martinů: Piano Quintet No. 2

Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) was forced to escape his native homeland, and he held a lectureship at Princeton University in the United States. Among his colleagues was none other than Albert Einstein, whom he met in December 1943. Einstein gave him a signed copy of his “The Evolution of Physics,” and suggested that physics and music shared the idea of interconnected realities. Martinů later wrote to a friend, “Neither you nor I nor anyone else can know all the components that make up the composition. Naturally, if we could all know, all problems would disappear.”

Bohuslav Martinů’s Piano Quintet No. 2

Martinů’s Second Piano Quintet dates from 1944, and straight from the dreamy opening, the composer offers his personal blend of impressionistic harmony and sweetly lyrical melodies. The “Adagio” is one of the finest efforts in this medium, and the “Finale” establishes an unsettled emotional climate. To a critic, “this is certainly one of the best piano quintets of the 20th century. I hope you enjoyed these selections as much as I have enjoyed compiling them. Actually, I believe there is one more episode coming up shortly. Thank you for listening.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter