Music on Wars and World Crises

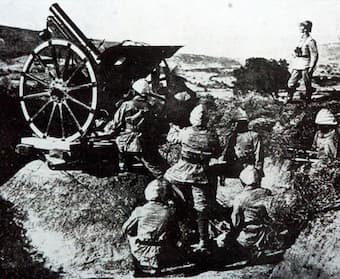

The Ottoman soldiers defending the Arıburnu shores from the Allied soldiers.

There is a lot of music that takes place during war, such as the marching songs that help you get your troops in place, the campfire songs to encourage comradery off the battlefield, and the like.

What happens afterward? We have pieces such as Britten’s War Requiem, Op. 66. Completed in 1962, it was given its premiere at the consecration of the rebuilt Coventry Cathedral. Combining Latin requiem texts with war poetry by Wilfred Owen, it was a powerful work, made more so by the request that there be no applause following its conclusion. We also have Arnold Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw, op. 46, written for narrator, men’s chorus, and orchestra and given its premiere in 1948 as a tribute to victims of the Holocaust.

Both those works use voices to emphasise the feelings in the music through poetry. What do we have if we drop off the language and let the music speak for itself? Chinese composer Wang Xilin was commissioned by the Chinese government for a work about the war… but they wanted him to use words and he refused. He thought the music should speak for those who no longer had voices. His Symphony No. 9, Requiem for the War of Chinese People’s Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World’s Anti-Fascist War, was given its sole performance on December 13, 2015. Performed by the China National Symphony Orchestra and its choir, and the choir of Capital Normal University, and including a baritone and a soprano soloist, the composer kept to his vow of no words. The singers cry, shout, even imitate gunshots, but there are no words that the composer could find to cover the horrors of the time.

We will look at some different war memorials, covering several different world crises.

The Turkish composer Can Atilla began to focus on the critical WWI battle of Gallipoli when he wrote the film score for Gallipoli 1915. A triumph for the Turk and a disaster for the Australian and New Zealand troops were thrown at an impossible military goal, the Gallipoli Campaign lasted nearly 11 months, with each side losing a quarter of a million men.

Sami Yetik: The Battle of Arıburnu and the heroic defence

of the 57th Regiment (1915)

Atilla’s work memorializes the Ottoman 57th Infantry Regiment, which received uncompromising orders from their leader, Lieutenant Colonel Mustafa Kemal of ‘I do not order you to fight, I order you to die.’ The entire Regiment was either wounded or killed when they faced the Anzac invaders with nothing but bayonets.

Atilla’s work tries for a mediation between the two combatants: the first movement symbolizes bravery and victory, with each theme intertwining. A solo cello performs the main elegiac theme, standing for Lieutenant Colonel Hüseyin Avni Bey, commander of the 57th Regiment, pulling in themes to represent his feelings, his concerns, and his longing for his family. The movement closes with a death march for the loss of the regiment.

Can Attila: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, “Gallipoli – The 57th Regiment” (Onur Şenler, cello; Bilkent Symphony Orchestra; Burak Tüzün, cond.)

Charles Dixon: The Landing at ANZAC, April 1915

(Archives New Zealand, AAAC 898 NCWA Q388)

The last two movements are dedicated to the Anzac soldiers. The words sung in the third movement are those of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Turkish Republic. His address, written on the Gallipoli Martyrs’ Memorial, is addressed to all the soldiers. ‘You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore, rest in peace…’ and is addressed to the soldiers’ mothers as well, telling them that, their sons, ‘…having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.’

American composer Ian Krouse takes up a different war in his Fanfare. Commissioned for the 70th anniversary of the Korean War, Krouse’s Fanfare for the Heroes of the Korean War, is in a cinematic style, as requested by the commissioners of the work. The work was given its premiere on November 12, 2021, at the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in the city of Busan, South Korea, and, its premiere was accompanied by a display of 400 drones.

Ian Krouse: Fanfare for the Heroes of the Korean War, Op. 71 (Seocho Philharmonia; Jong Hoon Bae, cond.)

Before China was part of the international war of the 1940s, it was involved in its own war with Japan. Starting with an incident in Beijing in 1937, the Second Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945, has become for many scholars the true start of WWII in Asia. China fought Japan with the aid of the Soviet Union, the US, and the UK, and the whole conflict eventually became subsumed into the larger China-Burma-India Theatre.

Chinese composer Yunjie Wang completed the work in 1966 and wrote in the familiar Chinese post-war musical style, with heroic marching sections, battle sections, and strong lyrical sections.

Yunjie Wang: Symphony No. 2, “The War of Resistance Against Japan” – I. The War of Resistance (Shanghai Orchestra; Peng Cao, cond.)

Canada, as part of the contribution of the English Commonwealth forces, participated in a joint UK-Canada raid on the French port of Dieppe in August 1942. The raid was a complete failure, with some 60% of the attackers being killed. The raiders were primarily Canadian, operating with the support of the Royal Air Force, but got bogged down on the beach and had to retreat after only 6 hours.

Dieppe’s chert beach and cliff immediately following the raid on 19 August 1942.

A Dingo Scout Car has been abandoned.

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-362-2211-04 / Jörgensen)

French composer Aubert Lemeland (1932-2010) wrote his Memorial, Op. 158, Dieppe, 19-08-1942 in 1993, in memory of the dead. The composer said his ‘musical impressions are presented like the backwash of waves coming to die on the line of grey pebbles of the Dieppe beach amongst the debris of a defeated armada….’ He closes the work with ‘…a brief chaconne in the spirit of Handel brings out a stable motif in the orchestra, creating the image of a final ‘In paradisum’.

Aubert Lemeland: Memorial, Op. 158, “Dieppe, 19-08-1942” (Rhenish State Philharmonic Orchestra; José Serebrier, cond.)

One learns from losses: the Allied forces found better ways to attack from sea in preparation for the D-Day landing two years later and the Germans found ways to improve their sea defenses.

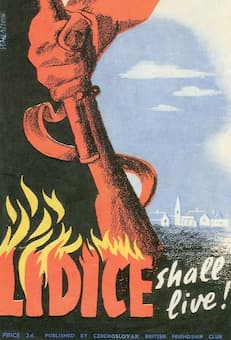

British poster commemorating Lidice

In June 1942, in retaliation for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, the cruel regional governor, the entire Czech town of Lidice was completely destroyed, and the people killed or sent to concentration camps. By the end of the war, only 3 men (who had been in prison and two in the RAF), 143 women, and 17 children survived of the original population of 503.

When the Germans broadcast news of the massacre, international reaction was swift: English coal miners started a fund for rebuilding the village after the war, a neighborhood in Mexico City, a hospital in Caracas, Venezuela, and a city in Illinois renamed themselves Lidice. Streets, alleys, and parks in the UK, Chile, Bulgaria and the US were renamed or built in memory of Lidice.

Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů wrote his Památník Lidicim (Memorial to Lidice) in 1943. The piece quotes from the Czech St Wenceslas Chorale and, in the climax of the piece, the opening notes of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony. The opening of Beethoven’s work had been transformed into Morse code (dot-dot-dot-dash = V) and had been used by the BBC in its wartime broadcasts as the symbol of V for Victory.

Bohuslav Martinů: Pamatnik Lidicim (Memorial to Lidice), H. 296 (Philadelphia Orchestra; Christoph Eschenbach, cond.)

The 26-part television documentary The World at War was originally broadcast in 1973 and 1974 by the BBC and has been rebroadcast around the world in the 1970s, 1980s, 2000s and 2010s. The series was ground-breaking for its use of contemporary film footage and interviews with survivors of both the war and the concentration camps. The music for the series was written by Carl Davis and was noted immediately for its dark opening theme.

Carl Davis: The World at War (concert version) (Czech National Symphony Orchestra; Carl Davis, cond.)

War memorials to this point have been from the outside: American poet Walt Whitman knew the American Civil War from the inside. Too old to be a soldier, he volunteered as a nurse in the army hospitals, where he wrote many letters to the families of sick soldiers. His poem ‘Come Up From the Fields Father’ tells of the reception of one of those letters coming to an Ohio farm family. Although the letter, from the hospital, reports, in his voice that he’s At present low, but will soon be better, the mother notes that the letter isn’t in her son’s hand. The narrator tells us what is to come: While they stand at home at the door he is dead already, The only son is dead.

American composer Richard Danielpour included this poem as part of his Whitman vocal cycle War Songs. Although the title is addressed to the father of the stricken son, the poem focuses on the mother, who, by the end only wishes to be dead herself, to be with her dear dead son. Danielpour’s setting of the poem was on commission from the Curtis Institute of Music – after completing it, he added the other 4 poems of the cycle. Danielpour was inspired by images he saw in the New York Times of the young men and women who had been killed in the Iraq War. Danielpour wanted to shift the focus from the visual of war to the visceral reality of loss.

Richard Danielpour: War Songs – No. 5. Come Up From the Fields Father (Thomas Hampson, baritone; Nashville Symphony Orchestra; Giancarlo Guerrero, cond.)

By ending with the voice of the dying and the reaction of those left behind, to live in mourning, we step back from the smoothed-over images of atrocities to the real-life effect of death.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter