Johan de Meij: The Venetian Collection

Johan de Meij

Dutch composer Johann de Meij (b. 1954) was inspired by four paintings in the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice to create his own Venetian Collection. The paintings he chose come from some of the most important and idiosyncratic 20th-century artists: René Magritte, Paul Klee, and Giorgio de Chirico.

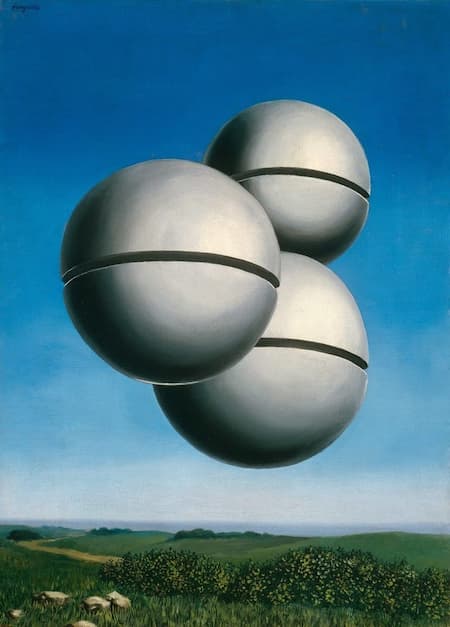

René Magritte’s La Voix des Airs (Voice of Space) was created in 1931 and shows the influence of de Chirico through its stripping away of function and meaning while creating an arresting and compelling image. Here, three bells float in the air. The precision with which they have been painted, above an equally credible landscape that seems almost Renaissance in its clarity.

Magritte: Voice of Space, 1931 (Venice: Peggy Guggenheim Collection)

In his musical impression of this image, Meij focuses on the bells’ sound in space, leaving time for the sounds to resonate over the landscape. Ominous sounds in the low strings make us question the potential safety of the hanging bells – is there something we should be wary of there? The landscape doesn’t seem to enter into the musical imagery, but it does urge us to keep an eye on what’s overhead. The piece ends with a return to silence.

Johan de Meij: The Venetian Collection – I. Voice of Space (Peabody Conservatory Wind Ensemble; Harlan D. Parker, cond.)

Giorgio de Chirico’s La Tour rouge (The Red Tower) shows a similarly depopulated landscape dominated by a shape, in this case, a red cylindrical tower. De Chirico gives us shadows and light, an obsessional focus on the tower, yet with all the trappings of a normal Italian piazza: arcaded buildings and a heroic statue. Yet, no Italian town with that kind of statue would have a view to a tower like this. There would be a wall, or another building, or the other side of the piazza.

de Chirico: La Tour rouge, 1913 (Venice: Peggy Guggenheim Collection)

Meij immediate involves us in an action that moves and stills. Again, there is time for sound to resonate and return while we freeze in our tracks. There’s a menace in the music – tensions building and then releasing abruptly.

Johan de Meij: The Venetian Collection – II. The Red Tower (Peabody Conservatory Wind Ensemble; Harlan D. Parker, cond.)

Paul Klee returned to Dessau in 1926 to resume his work at the Bauhaus. One of the works he produced there was Zaubergarten (Magic Garden), which combines architecture, geometric forms, sculptural figures, and wall etchings. One writer imagines the scenario where a ‘cosmic eruption seems to have spewed forth forms that are morphologically related…’ and it’s all placed on a highly textured surface that has worn down through time.

Klee: Zaubergarten, March 1926 (Venice: Peggy Guggenheim Collection)

Meij changes to a transparent texture to illustrated Klee’s dream world. Woodwinds come to the fore and the tempo gradually increases, gaining an urgency that tick-tocks us forward. The work closes with ‘a breathtakingly fast unison passage for the complete woodwind group.’

Johan de Meij: The Venetian Collection – III. Magic Garden (Peabody Conservatory Wind Ensemble; Harlan D. Parker, cond.)

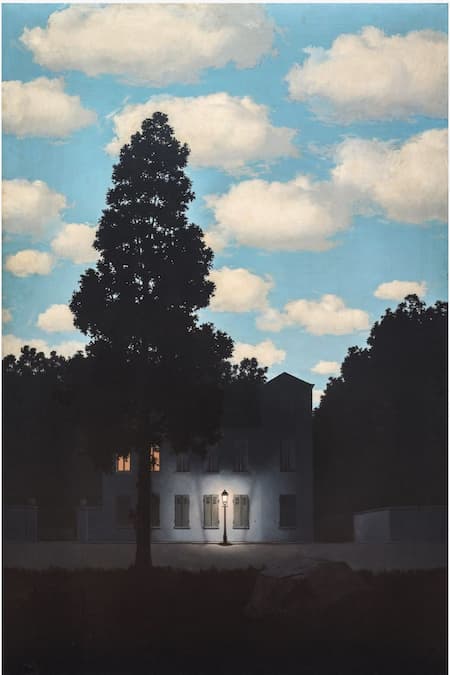

We return to Magritte for the last movement and a painting that is emblematic of much of Magritte’s style. Many copies of this exist in addition to this one in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection (such as those at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Menil Collection, Houston, and the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels). Below, the street is dark, the house is shuttered for the night, a golden light comes from an upstairs room, the street is dark, illuminated by the white light of a street lamp. Above the roofline and the trees, however, daylight still reigns and fluffy clouds are scatted across the blue sky. The paradoxical juxtaposition of day and night in this Surrealist painting makes the day seem lighter and the night darker.

Magritte: Empire of Light, 1953-54 (Venice: Peggy Guggenheim Collection)

One thing to realize is that this picture is big – standing over six feet (195.4 x 131.2 cm ) tall and filling a wall floor to ceiling. Standing in front of it is much like standing on the actual street, looking at the building before your eye is drawn up to the improbable sky.

Magritte: Empire of Light in context

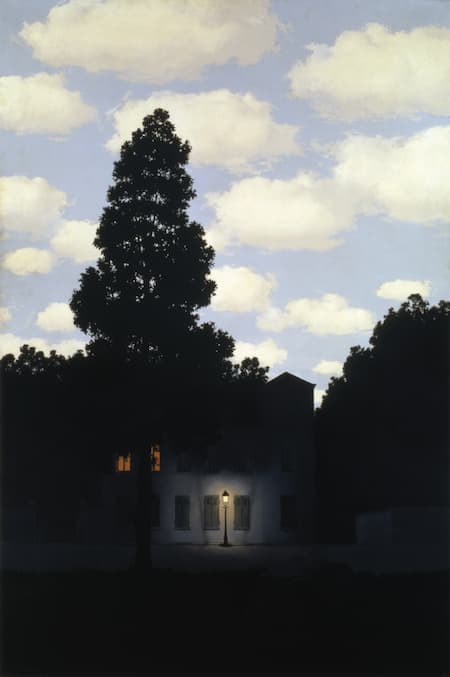

Other versions of this, such as that in MoMa, New York, show longer streetscapes, more room lights, and fewer clouds. The one in The Menil Collection has a lighter blue sky, evenly spaced trees bordering the water in front of the house, and a salmon colour to the house. The version in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique is much like the Guggenheim work except the lamppost reflects in water. In total, Magritte painted 27 versions of this image in different media (gouache, oil) and in different orientations, some horizontal, some vertical.

Magritte: The Empire of Light II, 1950 (New York: MoMA)

Magritte: L’empire des lumières, 1954 (Brussels: Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique)

The reason for the number of paintings of this same image was market demand. At its first showing in the 1954 Venice Biennale, the painting was sold to Peggy Guggenheim. Magritte then went on to paint different versions for each of the four unsuccessful bidders for the painting in 1954 and continued painting it for the next decade.

Where does Meij take us in his music for this work of art? He starts in the dark, with singing lower brass and a menace in the darker sounds of those voices. In the end, though, we rise up into the sky, leaving the dark world below.

Johan de Meij: The Venetian Collection – IV. Empire of Light (Peabody Conservatory Wind Ensemble; Harlan D. Parker, cond.)

Meij takes these very different worlds, mostly Surreal, and takes us on a tour. Sometimes he’s giving us the feeling of the work, sometimes the textures of the work, and sometimes everything that we imagine about a work. It’s a wonderful and private tour all at once.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter