Franz Liszt (1811-1886) was the greatest piano virtuoso of his time, possibly the greatest of all time. His sensational technique and captivating concert personality made him the ultimate rock star of the 19th century.

Franz Liszt

With his set of twelve Transcendental Études, the composer created one of the most challenging and towering monuments to modern piano writing. Between 1826 and 1852, Liszt produced works that pushed the boundaries of piano technique by exploring complex fingerings, rapid passagework, and intricate dynamics.

While they are often seen as a showcase for technical brilliance, Liszt’s Études also possess deep musicality, revealing rich harmonic textures and striking contrasts in mood. These works not only reflect Liszt’s innovative approach to composition but also his desire to elevate the piano as a vehicle for expressive virtuosity.

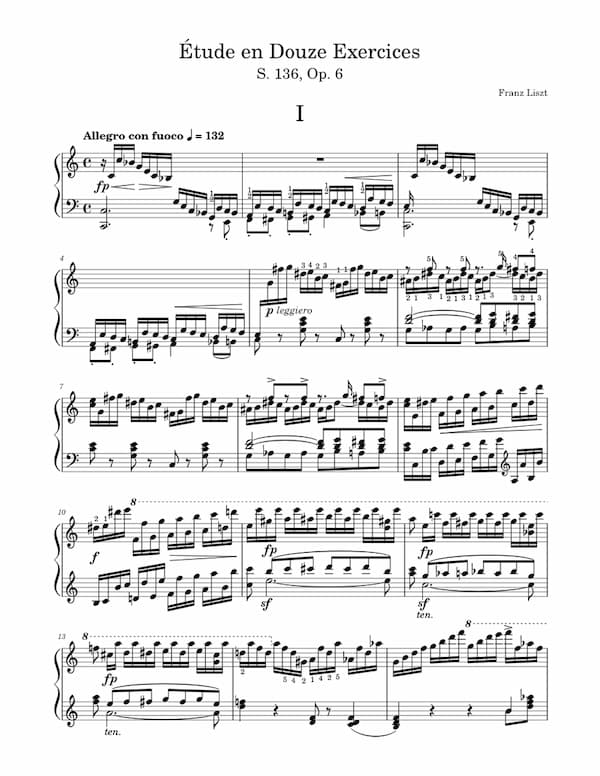

Liszt published his Etude pour le piano en quarante-huit exercices dans tous les tons majeurs et mineurs, Op. 6 in 1827—later his Op.1, when he was sixteen years old. These etudes formed the basis of later revisions, resulting in the Vingt-quatre grandes études of 1837. After further revisions these became the Etudes d’exécution transcendante published in 1851. Let us put the three different versions side by side and show the fascinating evolution of Liszt’s technical and artistic approach.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 1 in C Major “Allegro con fuoco” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

The 3 Etudes in C Major

Franz Liszt’s Etude en Douze Exercises, No. 1

The Etudes en douze exercices of 1826 are Liszt’s first serious contributions to the piano repertoire. At that time he was studying under the guidance of Carl Czerny, himself a student of Beethoven. Czerny’s influence is evident in the technical nature of these etudes as many resemble pedagogical exercises. However, these works already demonstrate some of the characteristics that would define his later works.

Liszt had set out to emulate the 48 Preludes and Fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach. That original intention is clear in the choice of keys, as the etudes start in C major and A minor, and continue as pairs along the circle of fifths. In the end, Liszt limited the set to six major and six minor studies, “creating within these tender romantic essays the basis for a pilgrimage through keyboard technique.”

The initial C-Major etude is built around a series of brilliant arpeggios, rapid scales, and complex chords in contrasting registers of the piano. Structurally, it is rather simple and straightforward, as it focuses on a study in basic technical patterns.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 1 in C Major “Presto” (1837) (Idil Biret, piano)

Liszt apparently played some of his early etudes in concert, and they are dedicated to Lydie Garella, a young pianist who lived in Marseilles. As reported, Liszt played duets with her during his stay there. He later told his biographer Lina Ramann that “he had had an adolescent crush on the girl and that the dedication was intended as an act of homage to the object of this early, uncharacteristically innocent love.”

Marie d’Agoult

Liszt withdrew from the public platform in 1828, but he was, as Jim Samson put it, “roused from his lethargy and morbid brooding by performances of Paganini.” Liszt resumed his career as a professional pianist, he met Marie d’Agoult, and embarked on a set of Grandes Etudes. As he requested a copy of his 1826 published Etudes from his mother, he was seemingly thinking of re-composing his earlier studies. The result was the set of twelve Grandes Etudes loosely based on the early exercise.

The overall tonal scheme stayed the same, but as Samson writes, “the clean, classical cut of the originals was replaced by a fierce, hugely challenging virtuosity, stretching even the most developed technique of the day to its limits.” The first study, now marked “Presto” rather than “Allegro con fuoco,” still focuses on arpeggios, but it introduces far greater technical difficulties, with faster passagework, more frequent hand crossings, and increased demands on finger independence. Liszt begins to push the boundaries of pianistic technique, showcasing more intricate and rapid hand coordination.

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 1 “Preludio” (1852)

In his Grandes Etudes of 1837, Liszt took advantage of the instrument made by Sébastien Érard, equipped with an ingenious mechanism called “double escapement,” which allowed for rapid repetition of the same note. His Paganini Studies appeared in 1837, and he would add the first two books of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage) shortly thereafter.

Liszt left Paris in 1848, after his break with Marie d’Agoult, and settled in Weimar as Kapellmeister to the Grand Duke Charles Alexander. And while he composed some new works, he also set upon some definitive revisions of some earlier works. It was in Weimar in 1852, after several modifications and the visual clarification of certain dangerous passages in the Grandes Études, that he produced the third and final version, known as Études d’exécution transcendante. As Kirill Gerstein writes, “whatever might have been overwrought in the 1837 version is now streamlined and really perfected.”

The reworked set now opens with a short study simply called “Preludio.” It is still in C Major, and one enormous crescendo forms an imposing introduction to the series. As Luis de Moura Castro writes, “this short piece crosses the sky as an arrow without even being aware of its ephemeral and brilliant quality.” And according to Busoni, “the Preludio is less a prelude to the cycle than a prelude to test the instrument and the disposition of the performer after stepping onto the concert platform.”

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 2 in A minor “Allegro non molto” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

The 3 Etudes in A minor

Carl Czerny

Between early 1822 and 1823, Franz Liszt studied with Carl Czerny for a period of 10 months. Although Czerny’s reputation as a composer has been much assailed, he might well be regarded as the first modern piano teacher. He sought to develop performance as a highly specialised and professional skill, completely separate from composition and all-round training in music. As Jim Samson reports, “his piano workshop provided a training for the budding virtuoso, a training that embraces everything from finger technique to dress and deportment.”

Czerny’s handwriting is all over the A-minor etude from the 1826 set. The focus is once again on arpeggiation, as it traverses multiple registers of the piano. The arpeggios alternate between both hands, and the phrasing calls for smoothness and evenness, with some hand crossing. This etude demands precision, hand coordination, smoothness, and clarity, all fundamental elements of the Lisztian pianistic style that would later evolve into much more complex and virtuosic works.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 2 in A minor “Molto vivace” (1837) (Idil Biret, piano)

Ferruccio Busoni wrote in his introduction to the 1837 set, “The Liszt whom we meet here has shot up to an unexpected height. Apparently, without transition, Liszt surpassed all available and imaginable possibilities of the piano, and he never made such an immeasurable stride again.” Robert Schumann wrote unfavourable of the new studies, actually preferring the original set of 1826. He suggested that Liszt’s virtuosity as a performer had prevented him from developing as a composer.

For the 1837 study in A-minor, Liszt changed the tempo direction from “Allegro non molto” to “Molto vivace.” It borrows the idea of arpeggiation from the earlier set, but it is now much more elaborate in figuration. The ascending left-hand arpeggiation is set against syncopated chords in the right hand. It also offers an early exploration into the realms of emotional expressiveness, harmonic experimentation, and technical innovation.

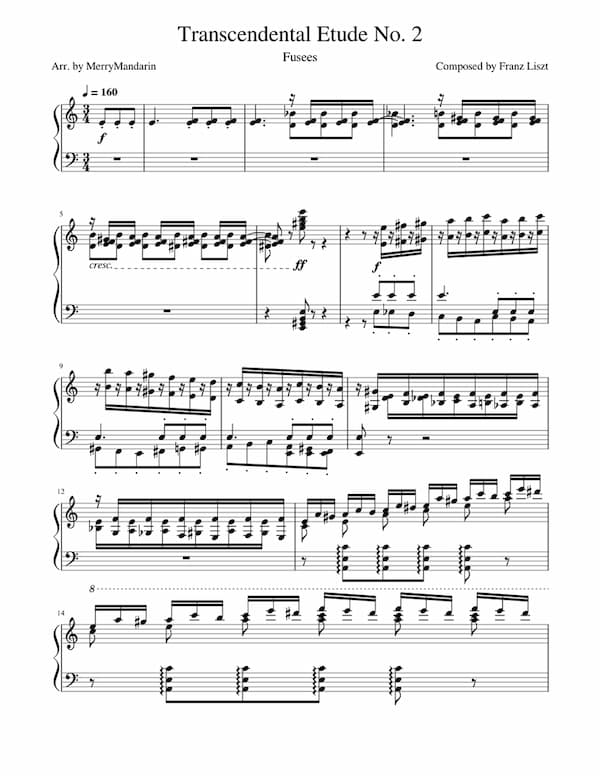

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 2 in A minor (Fusées)

Both the 1837 and 1852 sets are dedicated to Czerny, “in testimony to recognition and respectful friendship,” and they are humbly signed by “his pupil F. Liszt.” As indicated by the title, these works had nothing in common with conventional technical exercises with their repetitive mechanical drills. These were pages of high-level acrobatics for concert performance and displayed Liszt’s superiority over all his rivals.

Franz Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes No. 2

The “Transcendental Étude No. 2” occasionally makes use of the alternate title Fusées (Rockets). Liszt did not provide that particular title nor was it approved by him. Rather, it was added by Busoni in his edition of the etudes. The piece is extremely volatile as it features alternating and overlapping hands, with both hands playing the same note alternatingly. As difficulties increase, the right hand jumps across the keyboard, and both hands alternate fierce, high-pitched chords. The climax features a five-octave note span, followed by dramatic arpeggios and chords, before ending in a final release.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 3 in F Major “Allegro sempre legato” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

The 3 Etudes in F Major

Liszt, perhaps surprisingly decided that the two early versions of his etudes should no longer be circulated. He bought the engraved plates from the publisher Haslinger around 1852 and put him under contract not to sell any more copies. Sadly, Liszt Editions in the 20th century took this at face value and suppressed the earlier versions, arguing that they “do not represent Liszt’s final thoughts.”

Fortunately, we now understand that for Liszt, a composition was rarely finished. As Alan Walker writes, “all his life he went on reshaping, reworking, adding, subtracting; sometimes a composition exists in four or five different versions simultaneously.” Fortunately, we do look at things in a different light today. As such, we are able to appreciate the incipient “Allegro sempre legato” from the 1826 set.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 3 in F Major “Poco adagio” (1837) (Idil Biret, piano)

For the 1837 version, Liszt changed the tempo indication to “Poco adagio,” and the meter from 4/4 to 6/8. With the additional instruction “sempre legato e tranquillo” the left hand accompanies a singing melody in octaves in the right, leading, through a brief excursion in D flat major, to a passage marked “Un poco più animato il tempo” with staccato chords, “sotto voce e sempre dolcissimo.” Soon we reach a dynamic climax, followed by a “presto agitato assai,” subsiding to a concluding “dolce pastorale.”

Liszt titled the F-Major etude “Paysage” (Landscape) in 1851, and he altered its atmosphere to accord with this new suggestion. Liszt depicts a pastoral vision or memory of a nature scene as the music unfolds as a calm and plaintive song in the style of a nocturne. Legato lyricism, voicing, and cantabile playing take centre stage, and he deleted the climax he had written for the 1837 version, deeming it “superfluous.”

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 3 in F Major “Paysage”

The 3 Etudes in D minor

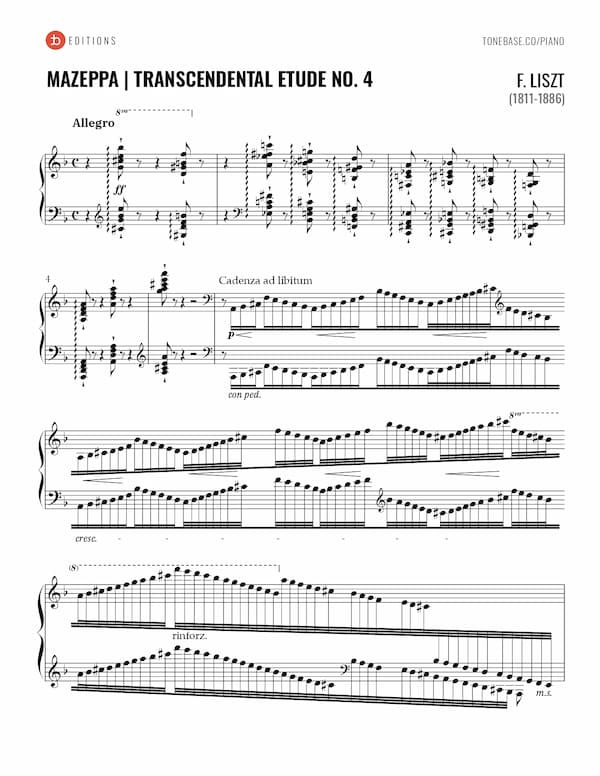

Franz Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes – Mazeppa

The D-minor study of 1826 primarily focuses on the successions of parallel thirds and accuracy in crossing and positioning the hands. This relatively straightforward study in thirds eventually achieved notoriety “as being rated at the highest difficulty in the set of Transcendental Etudes.” In its cocoon form of 1826, it does not even hint at what was to come.

While the 1826 versions, in general, primarily contain the melodic basis for the later sets, in the case of the D-minor, you will undoubtedly hear the harmonic outline of what will eventually become the famous “Mazeppa.”

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 4 in D minor “Allegretto grazioso” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

The simple cross-hand exercise of 1826 changes from an “Allegretto” to a “Allegro patetico” in the 1837 version. Curiously, the 1837 version of the piece begins in a rather less complicated way than its 1851 counterpart, and plunges straight into the principal material, with triplet chord accompaniment.

I am not sure when Liszt came up with the title “Mazeppa,” but it was probably after 1837. It references a poem by Victor Hugo, based on an epic poem by Lord Byron. It tells the morbid tale of the Ukrainian page caught seducing a noble Polish lady. As punishment for his indiscretion, Mazeppa is tied naked to a wild horse and chased into the Ukrainian steppes. The horse eventually dies of exhaustion, and Mazeppa, close to death, has visions of Ukrainian independence.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 4 in D minor “Allegro patetico” (1837) (Idil Biret, piano)

Liszt certainly felt inspired by the story, and there is an extended piano composition titled “Mazeppa” dating from 1840. He also returned to the same subject for his sixth symphonic poem, composed during his tenure in Weimar at the beginning of the 1850s. As for the “Transcendental Étude” No. 4 in D minor, it starts with an elaborate cadenza not found in the earlier studies.

Often cited as a prime example of empty virtuosity, the galloping theme is initially sounded in octave. The “Lo stesso tempo” section features a modified theme in the left hand while the right hand plays arpeggios. The theme returns in a more passionate form, and eventually in a breathtaking “Allegro deciso.” The piece concludes with a grand finale, representing the final line of the poem, “he falls then rises a king.” Please join me for part 2, coming up shortly.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter