Franz Liszt: Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage)

Over his life, Franz Liszt (1811–1886) travelled widely. From his start in Hungary, through his first concerts as a child, his training in Vienna, his life in Paris, living with Countess Marie D’Agoult in Geneva, touring Europe as a concert pianist, and so on. He brought these experiences together in three piano suites, entitled the Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage).

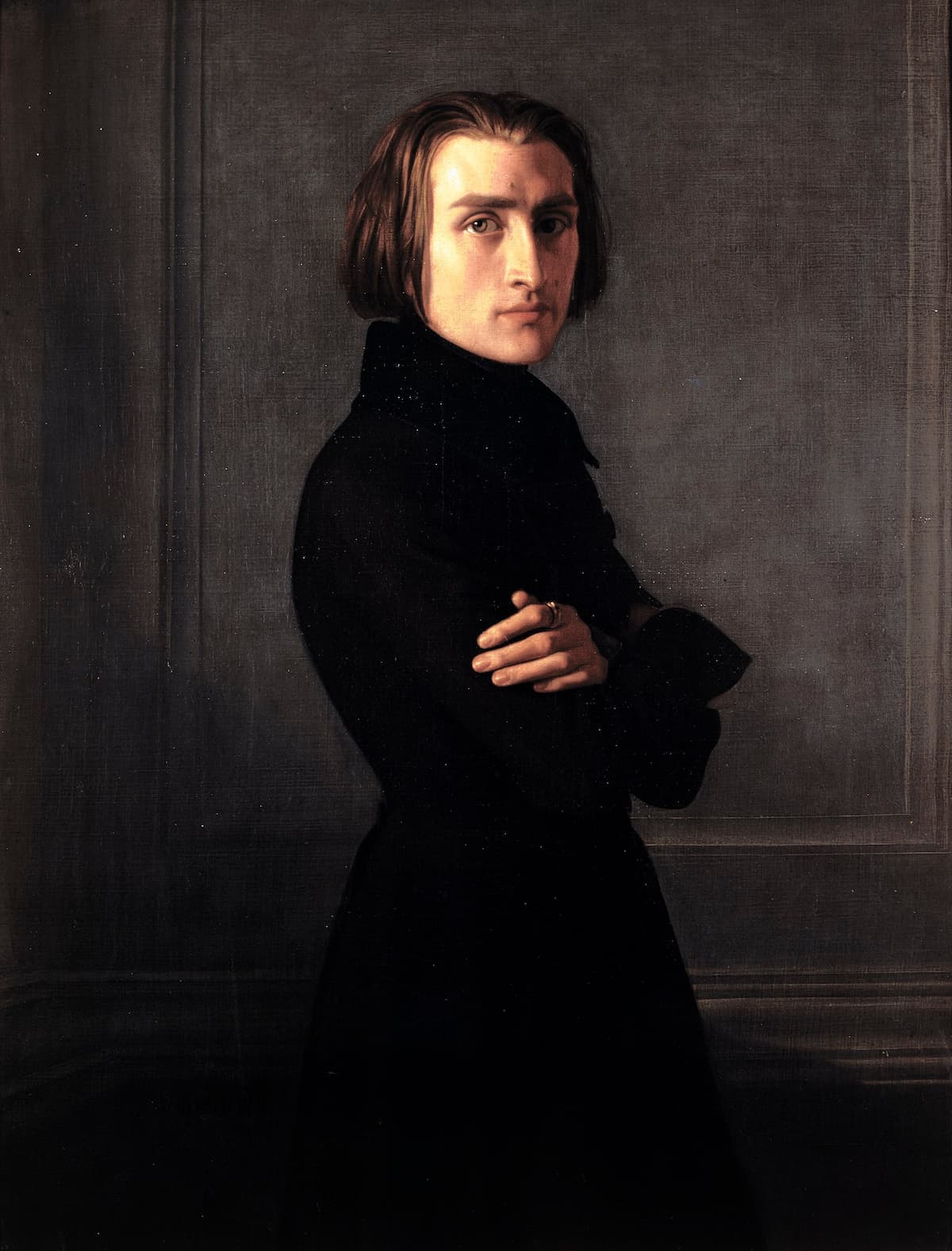

Henri Lehmann: Liszt, 1839

The first year was devoted to Switzerland and held works composed between 1848 and 1854; the first set was published in 1855. The second year was Italy, and was composed between 1837 and 1849 and was published in 1859. The third set is not devoted to a single country and was published in 1883. The 7 works in the third set were composed in 1867 (no. 7), 1872 (no. 5), and 1877 (nos 1–4 and 7).

The first two pieces of the Italian set are based on two pieces of art: Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin (1504) and Michelangelo’s The Thinker (1534).

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483–1520), better known simply as Raphael, painted Lo Sposalizio (The Marriage of the Virgin). It was completed in 1504, when Raphael was 21. His teacher, Pietro Perugino, had been commissioned to do the work but passed it on to his student.

Raphael: Lo Sposalizio (The Marriage of the Virgin), 1504 (Milan: Pinocoteca di Brera)

The painting is based on earlier works by Perugino, another wedding of the Virgin picture and a fresco in the Sistine Chapel showing Christ passing the keys of the church to Saint Peter.

In this compilation picture below, on the left is Perugino’s Sposalizio della Vergine, in the middle is Consegna delle chiavi (Delivery of the Keys), and on the right is Raphael’s Lo Sposalizio.

Comparing Perugina (left and middle) and Raphael (right)

Many of the elements are the same, yet Raphael added his own distinct details, such as his signature over the door, the brighter colours used in the clothing (our eyes are drawn to Mary’s red dress and then see it echoed throughout the painting), and the action of the mad in orange tights. Each of the suitors behind Joseph holds a wooden wand. Only the branch held by Mary’s future spouse would flower, as Joseph’s has. Everyone else stick’s is barren and the man in the orange tights is furiously trying to break his over his knee. In an analysis of viewpoint, the viewer of Raphael’s painting is not on the same level as the subjects, as in Perugino’s works. Instead, the viewer looks down from a slightly elevated position. The temple in the background is no longer just a decorative element. Its height and its complete portrayal integrate it into the painting more than the buildings in Perugino’s models do. And so, we are drawn into the painting through our elevated position and the way the building pulls us through its central door.

Musically, Liszt’s musical painting of Mary and Joseph’s marriage takes two themes and combines them to symbolize the joining together of the two.

Franz Liszt: Années de pèlerinage, 2nd year, Italy, S161/R10b – No. 1. Sposalizio (Marriage of the Virgin) (Jenő Jandó, piano)

The second piece in the Italian set is entitled Il pensieroso (The Thinker). This is not Rodin’s hunched-over man but Michelangelo’s sculpture of Lorenzo de Medici for the Medici tomb in Florence.

Michelangelo: Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino, 1534 (Florence, San Lorenzo)

The figure of the young duke, shows him seated clothed in the dress of an ancient Roman and in an attitude of thought. Much of the detail can be read with models in other Michelangelo works: the turning of the right hand, palm up, symbolizes the relaxation of the body in sleep (or death), the lion-mask helmet is a symbol of fortitude, and the animal-faced money box under his left elbow speaks of thrift. The hand on the mouth symbolizes silence. Other aspects seem to refer to melancholy. The foot of the statue carries a brief poem by Michelangelo where the statue expresses his gratefulness that, made of stone, he may sleep, while the world changes around him.

| Grato m’è il sonno, e piú l’esser di sasso. | I am grateful for sleep, and more for being stone. |

| Mentre che il danno e al vergogna dura. | While that the damage and the hard shame. |

| Non veder, non sentire m’è gran ventura | Not seeing, not hearing is a great fortune to me |

| Però non mi destar, deh’ – parla basso! | But don’t wake me up, ah – speak quietly! |

Liszt’s music seems to have a similar quiet contemplative style. There are some sforzando outbursts, but much of the music is simply marked ‘sotto voce’.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: Années de pèlerinage, 2nd year, Italy, S161/R10b – No. 1. Il penseroso (The Thinker) (Jenő Jandó, piano)

Culture ! Civilization ! Classics !