See here for the history of the prize.

Elliott Carter, 1960 © Los Angeles Times (Associated Press)

1960s

When we look at the awards for the 1960s, we see a distinct turn away from large symphonic works towards quartets and works that include new technology, such as electronic tape.

The 1960 winner was Elliott Carter for his String Quartet No. 2. This four-movement work has cadenzas on the end of each movement for individual instruments, first viola, then cello, then violin I. Each instrument is given indicative intervals:

Violin I: minor thirds, perfect fifths, major ninths, and major tenths

Violin II: major thirds, major sixths, and major sevenths

Viola, using augmented fourths, minor sevenths, and minor ninths,

Cello: perfect fourths, minor sixths, and minor tenths

All instruments share major and minor seconds.

It’s an interesting compositional strategy and gives us the first work in the Pulitzer Prize for Music that doesn’t follow the traditional tuning and organization we’ve been used to since 1943.

Elliott Carter: String Quartet No. 2 – IV. Allegro (Juilliard String Quartet)

Walter Piston

Walter Piston’s Symphony No. 7 was the 1961 Prize winner, following his 1948 award for his Symphony No. 3. Piston’s biographer called his Symphony No. 7 his ‘pastoral’ symphony, largely because of the slow movement theme. The slow movement’s English horn solo and later flute solo are indicative of his control of orchestral timbre. We shouldn’t forget that Piston was the author of the 1941 book Harmony, which is still used in music teaching today.

Walter Piston: Symphony No. 7 – II. Adagio pastorale (Oregon Symphony; Carlos Kalmar, cond.)

The Crucible, by Robert Ward © The Pulitzer Prizes

Robert Ward’s opera The Crucible, set Arthur Miller’s 1953 play about the Salem Witch Trials (or was that the Senate hearings on Communism?). Miller’s work won the 1953 Tony Award for Best Play. The opera was awarded the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for Music. Ward was commissioned by New York City Opera and Arthur Miller was involved in the selection committee.

Robert Ward: The Crucible: Act IV – Oh, God be praised! (Purchase Opera; Hugh Murphy, cond.)

Samuel Barber © Wikipedia

Samuel Barber, another dual winner, wrote his Piano Concerto on commission from the G Schirmer music publishing company in honour of their centenary. Its first performance was during the opening festivities for Philharmonic Hall at Lincoln Center in 1962; it was awarded the 1963 Pulitzer Prize. The concerto soloist was John Browning and Barber wrote the work with him in mind. However, when Browning told him that the third movement was unplayable at Barber’s desired tempo, Barber didn’t make any changes until Vladimir Horowitz reviewed it and agreed with Browning. Only then did Barber rewrite the part.

Samuel Barber: Piano Concerto, Op. 38 – III. Allegro molto (Stephen Prutsman, piano; Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

In 1964 and 1965, no prize was awarded. There was mention that the 1965 prize was going to be awarded to Duke Ellington, but in the end, this decision was changed, much to Ellington’s anger that jazz, the ultimate American musical genre, remained unrecognized. Ellington was recognized posthumously in 1999 with a Pulitzer Prize Special Award.

Leslie Bassett, professor at the University of Michigan School of Music, won in 1966 with his Variations for Orchestra.

Leslie Bassett: Variations for Orchestra

Leon Kirchner © Wise Music Classical

The 1967 work by Leon Kirchner was the first for electronic tape and ensemble. In 1967, in an interview with the composer, he discusses what he was trying to achieve by adding electronic tape to a string ensemble. He said that the traditional view of the electronic medium as one without boundaries always had to be tempered with the fact that it had to result in music at the end, not just sound: ‘…though the electronic sounds in my Quartet took four days to write, the notes took fifty years’ of his experience as a composer’. In this recording the string quartet noted that one of their initial problems was that, although the score was highly readable, the electronic medium of the tape had severely degenerated and needs months of work to get to a point of playability.

Leon Kirchner: String Quartet No. 3 (Boston Composers String Quartet; Leon Kirchner, electronic tape)

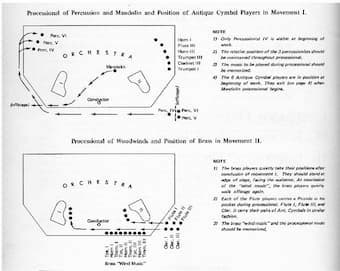

Movement diagrams for Echoes of Time and the River

George Crumb is known for his exploration of new musical timbres and the use of unusual instruments and performing techniques in achieving those new timbres. His 1968 Pulitzer Prize work Echoes of Time and the River was his expression ‘in musical terms the various qualities of metaphysical and psychological time.’ The subtitles for the piece are ‘Four Processionals for Orchestra’ and ‘Echoes II.’ Every movement includes processionals, where small groups of players move in carefully choreographed step-patterns around the stage. Percussion players move from the front corner to the diagonally opposite back corner, a mandolin player moves as he plays from center stage off to the wings. The players who don’t move are as critical as those who do move.

George Crumb: Echoes of Time and the River, “Echoes II” – IV. Last Echoes of Time (Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra; Thomas Conlin, cond.)

Karel Husa © The New York Times

Karel Husa’s String Quartet No. 3 was the final winner of the decade. The work is dedicated to the Fine Arts Quartet, who played the premiere of the work. The composer said that, unlike his earlier string quartets, this work ‘explores some solo predominance, spotlighting the several instruments in rather free forms: the viola in the first movement; violoncello in the second; the two violins in the third.’

Karel Husa: String Quartet No. 3 – I. Allegro moderato (Fine Arts Quartet)

The 1960s saw the Pulitzer Prize committee expanding its horizons towards atonality, political works (The Crucible), new performing media (electronic tape) and works for which choreography was as integral as the seated musicians.

Now, the 1970s!

The 1970s

Charles Wuorinen

© Howard Stokar / Wikipedia

Progressing from 1967’s Pulitzer Prize for electronic tape and string quartet, the Pulitzer Prize for 1970 went to a work with only electronics. Charles Wuorinen’s 4-channel electronic composition Time’s Encomium was the full wholly electronic piece to win and Wuorinen was the youngest composer, at age 30, to win. The word ‘encomium’ means ‘the praise of a person or thing’ and the thing that Wuorinen is praising is ‘time.’ The composer said ‘being electronic, Time’s Encomium has no inflective dimension. Its rhythm is always quantitative, never qualitative. Because I need time, I praise it; hence the title.’ The work was realized on the RCA Mark II synthesizer at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York.

Charles Wuorinen: Time’s Encomium – Part I (Charles Wuorinen, synthesizer)

Mario Davidovsky © The New York Times

The electronic theme continued in 1971 with Mario Davidovsky’s Synchronisms No. 6, written for piano and electronic sounds. Davidovsky came to the US from his native Argentina in 1960, brought by Aaron Copland. He was introduced to the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, where he worked for many years on his own compositions. He was director of the center from 1981 to 1993. His Synchronisms series which combined acoustic instruments and taped electronic sounds, from no. 1 in 1962 to no. 12 in 2006, were his best-known works. Synchronisms No. 6, for piano and electronic sound, was praised by the Pulitzer Committee for its ‘mastery of a new medium and its imaginative use in combination with the solo pianoforte.’

Mario Davidovsky: Synchronism No. 6 (Aleck Karis, piano)

Jacob Druckman © Wikipedia

Jacob Druckman was another graduate of The Juillliard School who then went on to spend time in Paris studying with Nadia Boulanger. Although he was known for his electronic music, it was for a large-scale orchestral work, Windows, that he was awarded the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for Music. His concept for Windows was not windows that look outward, but ‘windows inward. They are points of light which appear as the thick orchestral textures part, allowing us to hear, fleetingly, moments out of time – memories, not of any music that ever existed before, but memories of memories, shadows of ghosts. The imagery is as though, having looked at an unpeopled wall of windows, one looks away and sees the afterimage of a face.’ One of the compositional techniques used was the use of aleatoric processes, where some element of the music is left to chance. The work had been commissioned by the Serge Koussevitzky Music Foundation for conductor Bruno Maderna and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The piece is dedicated to conductor Serge Koussevitzky and his wife Natalie.

Jacob Druckman: Windows

Elliott Carter’s String Quartet No. 2 had been the winner in 1960 and in 1973, Carter’s String Quartet No. 3 was the winner. The work was created as sets of duos: Duo I is the first violin and the cello and Duo II is the second violin and viola. The first duo has four movements and Duo II has six movements, with each movement having a consistent interval. Duo I’s four movements, for example, are based on the major seventh, the perfect fourth, the minor sixth, and the minor third. The 10 movements are not played continuously but are fragmented and recombined to produce a potential 24 pairings between the duos. Carter’s intent was to have two distinct ensembles playing two pieces at once, clashing and creating new sound combinations. Another directive is that Duo II should play strictly in time throughout while Duo I plays with a measure of expressive freedom to maximize the contrast between the two groups. The work is extremely difficult to play, with the Juilliard String Quartet (arguably the best string quartet in the US) needing a year of rehearsals before they felt ready to give the première of the work.

Elliott Carter: String Quartet No. 3 – Duo II: Maestoso (giusto sempre) – / Duo I: Furioso (quasi rubato sempre) – (Pacifica Quartet)

Donald Martino © Wikipedia

Donald Martino’s Notturno was the 1974 winner. The work had been commissioned by the Naumburg Foundation and was written for the group Speculum Musicae. In a speech at Yale University in 1975, Martino said about the piece, that it was ‘a sort of “night music” descriptive of the moments before I go to sleep, when I’m reviewing the day, when all the miseries and the beauties come together in a kind of chaotic swirl without pattern. It’s about the diversity of feeling that I undergo daily when I contemplate my life at that moment before sleep.’

Donald Martino: Notturno: I. Liberamente – Alla misura – (New Millennium Ensemble)

Dominick Argento © Wikipedia

The first song cycle to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music was Dominick Argento’s From the Diary of Virginia Woolf in 1975. Extracts from Woolf’s diary were published in 1954 as A Writer’s Diary: Being Extracts from the Diary of Virginia Woolf. The work was very much in the tradition of Argento’s writing based on prose rather than poetry sources. The writing of the text is more free-form and confessional than poetry would be and this, in turn, frees the music to adapt to Woolf’s inner world.

Dominick Argento: From the Diary of Virginia Woolf – No. 2. Anxiety (October, 1920) (Linn Maxwell, mezzo-soprano; William Huckaby, piano)

Ned Rorem was the 1976 winner. His Air Music, a set of 10 variations, was given its premiere by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra.

Ned Rorem: Air Music: X. All Players (Louisville Orchestra; Peter Lenard cond.)

Richard Wernick’s Visions of Terror and Wonder, a work for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, was the 1977 winner. It had been commissioned by the Aspen Music Festival’s Conference on Contemporary Music, with assistance from the National Endowment for the Arts, and was given its premiere at the Festival.

Michael Colgrass © jordanrsmith.com

Michael Colgrass’ work Déjà vu for percussion quartet and orchestra was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and they gave its premiere under conductor Erich Leinsdorf. The title comes from his feeling of déjà vu when he was asked by the Philharmoic for a work for percussion, since, to him, that was his old life before he’d become a full-time composer. His current strong lyrical side was confronted by the less-than-lyrical qualities of percussion. His percussion instruments, the vibraphone, tuned drums, marimba, and chimes, are a mix of pitched (vibraphone, marimba and chimes) and non-changeable pitch (tuned drums).

Michael Colgrass: Déjà vu (version for percussion quartet and wind orchestra) (Timur Rubinshteyn, Jeffrey Means, William Klymus, and David Victor, percussion; New England Conservatory Wind Ensemble; Charles Peltz, cond.)

We close the decade with Joseph Schwantner’s Aftertones of Infinity. This symphonic poem was commissioned by the American Composers Orchestra and the premiere was given by the orchestra under the direction of Lukas Foss. The work has an extensive percussion section, including Japanese temple bells and glass harmonica. The latter instrument is important in the final section.

Joseph Schwanter: Aftertones of Infinity

The 1970s saw an expansion of the music awarded the Pulitzer Prize to include many more works for electronics and a sharp rise in the number of works where percussion instruments were integral to the sound and construction of the work.

Now, the 1980s!

The 1980s

David Del Tredici © David Del Tredici

The 1980 Pulitzer went to the New York composer David Del Tredici, who became fascinated with Lewis Carroll’s two books about the child Alice: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its 1871 sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. Del Tredici had started to set the works of Lewis Carroll as early as 1969, but it was his 1979 work, In Memory of a Summer Day, that captured the Prize committee’s attention for their 1980 award. The title comes from Carroll’s original dedication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to Alice Liddell: ‘A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer Day.’ The dedication was replaced in the published story with a poem, ‘All in the golden afternoon’ which tells the circumstances of the invention of Alice’s Wonderland. Del Tredici eventually combined In Memory of a Summer Day into his later and larger work Child Alice (1981).

David Del Tredici: Child Alice – Part 1, In Memory of a Summers Day

No Pulitzer Prize for Music was awarded in 1981.

Roger Sessions © Wikipedia

In 1982, Roger Sessions was awarded the Pulitzer for his last orchestral work, Concerto for Orchestra. Commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, its premiere was conducted by Seiji Ozawa. The work is dedicated to the conductor and was written for the orchestra on the 100th anniversary of its founding. In his note about the work at its premiere, Sessions first recalled how much the BSO meant to him over the past 70 years of attending their concerts and how each section of the work brings out each individual section of the orchestra. Sessions had been the earlier recipient of a Special Citation in Music in 1974.

Roger Sessions: Concerto for Orchestra

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich

Ellen Taaffee Zwilich became the first woman composer to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for music in 1983. Her Symphony No. 1, which is also titled Three Movements for Orchestra, was part of the move to her postmodern, neoromantic style that happened in the 1980s. The other work in 1983 that was a finalist, but which wasn’t awarded the prize was Vivian Fine’s orchestral suite Drama for Orchestra. The next woman composer wouldn’t be recognized until 1991 and then again in 1999 with a pause until 2010.

Ellen Taaffee Zwilich: Symphony No. 1 – III. Rondo

British-American composer Bernard Rands’ Canti del Sole (Songs of the Sun) was the 1984 Prize winner. In its 14 movements, it sets poetry from 14 different poets ranging from an anonymous 12th-century poet to modern works by Italian, French, Irish and British poets. The poems track the day from dawn to dusk and closes with Salvatore Quasimodo’s ‘Ed è subito sera.’

Bernard Rands: Canti del sole (version for voice and orchestra): No. 14. Ed è subito sera (Stephen Chaundy, tenor; BBC National Orchestra of Wales; William Boughton, cond.)

Stephen Albert © Stephen Albert

Stephen Albert’s Symphony No. 1, RiverRun, was the 1985 Prize winner, much to the composer’s surprise. He thought himself only marginally known and was looking for something to bring life to his career. He compared winning the Pulitzer Prize with looking for a gentle rainstorm and getting hit by lightning. He was a thoroughly tonal composer, believing that serialism had created a wall between the composer and the audience. The work was commissioned by the Sydney L. Hechinger Foundation for the National Symphony Orchestra. For Albert, the symphony, through the metaphor of the River, is a reflection on the Cycle of Life: Life–Death–Rebirth.

Stephen Albert: RiverRun, “Symphony No. 1” – I. Rain Music (Russian Philharmonic Orchestra; Paul Polivnick, cond.)

George Perle’s Wind Quintet No. 4 for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon was written on commission for the Dorian Wind Quintet. The work was the Pulitzer winner in 1986.

George Perle: Wind Quintet No. 4

John Harbison

John Harbison took his text for the 1987 Prize winner from the final verses of Matthew 3 (13-23) for The Flight into Egypt. This work for solo soprano and baritone, chorus and chamber orchestra was an examination of the darker side of Christmas: the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt in anticipation of Herod’s killing spree in Bethlehem, and their return to Nazareth and Galilee after the death of Herod. For the composer, like Stephen Albert before him, the awarding of the Pulitzer Prize came as a complete surprise because he wasn’t aware that his work was even being considered.

John Harbison: The Flight into Egypt

William Bolcom

In a return to a very old genre, that of the etude, the 1988 winner, William Bolcom’s 12 New Etudes for Piano (1977-1986), brought together tonality and non-tonal elements, fusing it into a dense chromaticism. The work had been originally created for pianist Paul Jacob, who died when only 9 were completed. Two performances, however, convinced him to write the final three. A performance of Nos. 1-3 by pianist John Musto and a performance of Nos. 1-9 by Canadian pianist Marc-André Hamelin. After hearing Hamelin’s performance, Bolcom returned home and completed the missing 3 Etudes in ‘a white heat.’

William Bolcom: 12 New Etudes

Parmigianino: Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror (c. 1524)

(Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum)

The final winner for the 1980s was Roger Reynolds for Whispers Out of Time. Credited as the ‘first experimentalist’ to capture the Pulitzer Prize, Reynolds is described as one of the composers born in the 1930s who found a new music in the rubble left by the deconstructed classical tradition that was a legacy of the 1920s. His avant-garde work takes its title from the last line of John Ashbery’s long poem, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. Reynolds reflects the poem’s changing images, just as the poem itself is a meditation on a sixteenth-century painting by Parmigianino.

Roger Reynolds: Whispers Out of Time – VI. The Portrait’s Will to Endure (Cleveland Chamber Symphony; Edwin London, cond.

In many ways, the 1980s awards were signals of new steps and new directions for the Prize. It’s astonishing that it took 40 years to recognize a woman composer but even more shameful that that recognition is still a rarity in the prize.

Next: The 1990s and the New Century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter