The lowest member of the string family is the double bass – its genetics place it closer to the viol than the violin in that it has sloping shoulders (see cello for a viola da gamba image), its body is proportionally deeper than the violin’s, and it’s tuned in fourths like a viol. Scholars go back and forth on its viol- or violin-family origins.

A cello and a double bass in the hands of Song Young-hoon, left, and double bassist Sung Min-je

As you look around the double bass section of your local orchestra, you may find variations on the basic form. More slope in the shoulders, a smaller lower section (the lower bout), or an extra extension piece. This piece, known as the C extension, extends the fingerboard and gives four extra low notes. To help the player, there are little gates or fingers so that the player can set the pitch he needs without having to reach over his head while playing.

C Extension

For much of its life, the double bass was the bass voice of an ensemble, with little melodic fun for the part. Starting with Haydn, however, concertos for the double bass began to appear. Haydn’s, unfortunately, was lost in a fire, but other composers from the early classic period wrote concertos as well, including Johann Baptist Wanhal, Franz Anton Hoffmeister (3 concertos), Leopold Kozeluch, Anton Zimmermann, Antonio Capuzzi, Wenzel Pichl (2 concertos), and Johannes Matthias Sperger (18 concertos). Mozart’s concert aria, Per questa bella mano, K. 612, for bass voice, double bass, and orchestra has some beautiful lines.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Per questa bella mano, K. 612 (Thomas Quasthoff, bass-baritone; Württemberg Chamber Orchestra of Heilbronn; Jörg Faerber, cond.)

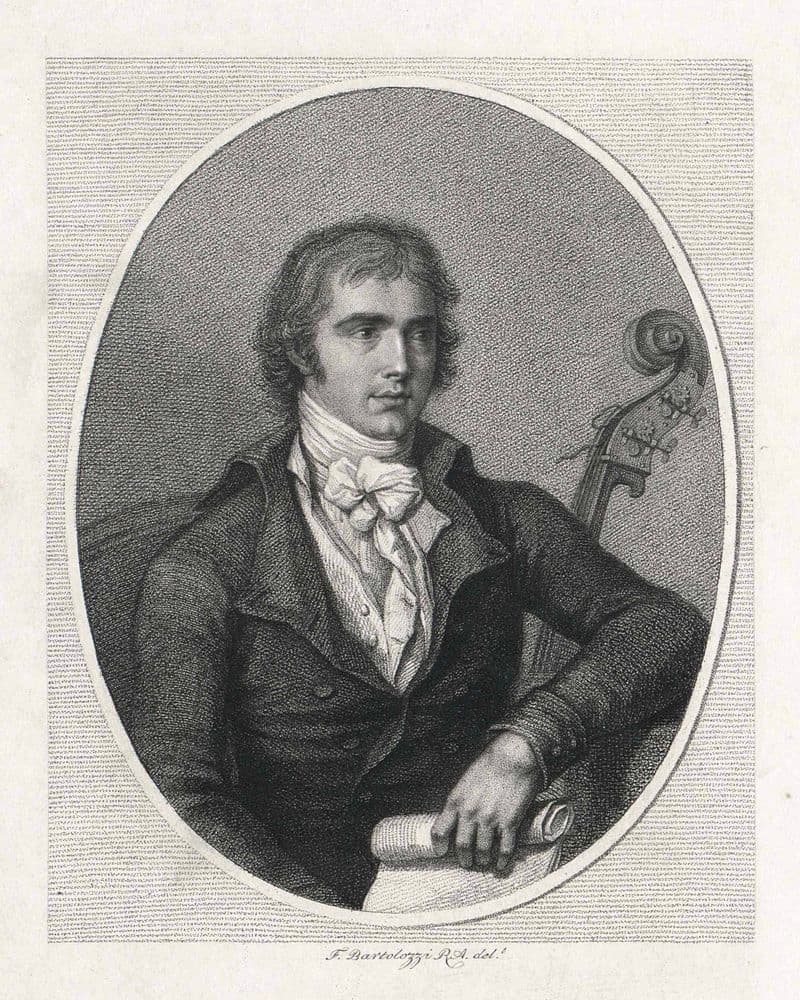

The double bass virtuoso Domenico Dragonetti, a friend of Haydn’s and Beethoven’s, inspired more composers to write for the instrument. After a career in Italy, he went to Russia and then to London as a performer. We can see that the double bass writing in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, the Seventh Symphony, and the Ninth Symphony is for the double bass alone and does not double the cello part.

Francesco Bartolozzi: Domenico Dragonetti, ca. 1780

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 – III. Allegro— (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

Giaochino Rossini met Dragonetti in London and wrote his Duetto in D major for Dragonetti and the cellist David Salomons.

Giaochino Rossini: Duetto in D Major (Maurizio Gambini, cello; Massimo Giorgi, double bass)

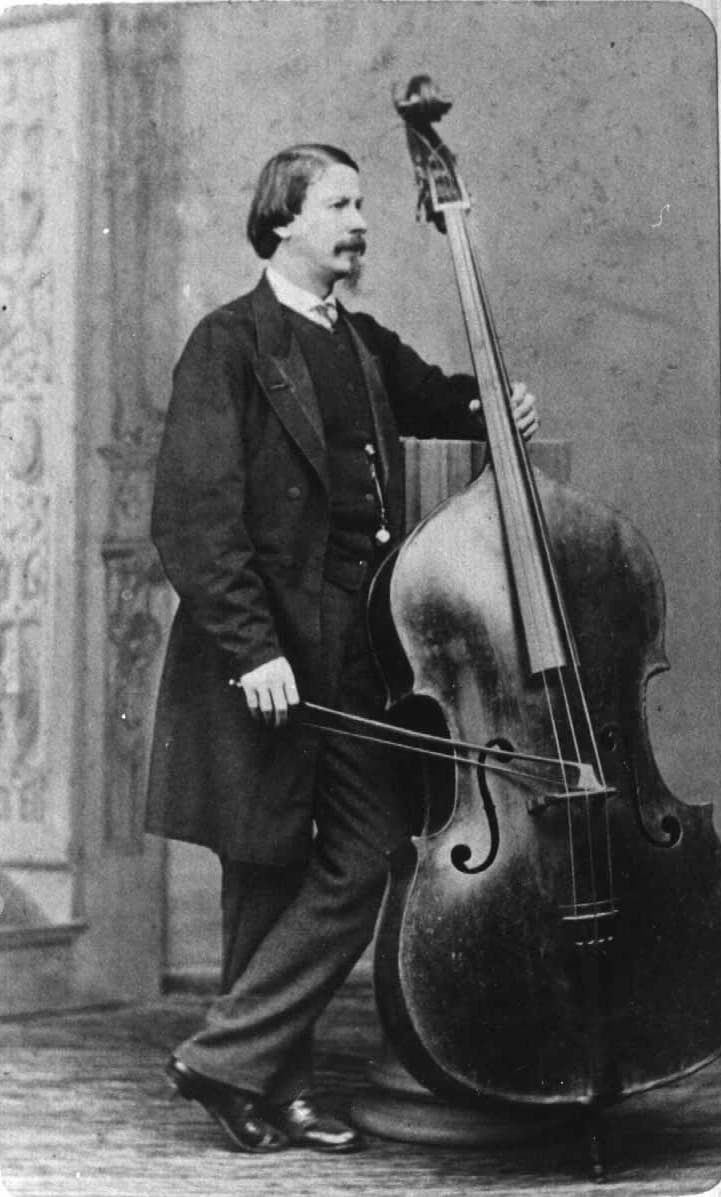

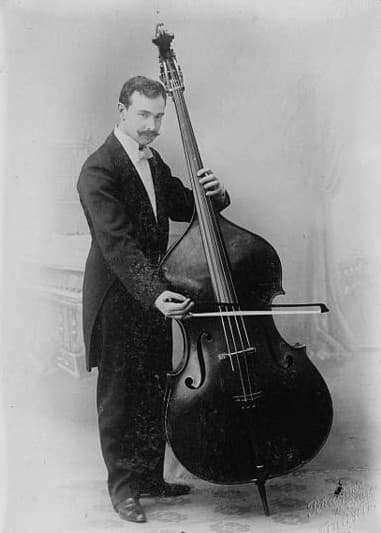

In the 19th century, Giovanni Bottesini was considered the ‘Paganini of the double bass’, and as an opera conductor, composer, and performer, he knew how to stand out. His double bass concertos were so technically challenging that, at the time, they were considered unplayable. For the modern bassist, however, they are part of the core repertoire. His First concerto, given its premiere in 1878, the singing slow movement shows the range of the instrument both technically and lyrically.

Bottesini with his Testore bass, ca. 1865

Giovanni Bottesini: Double Bass Concerto No. 1 in F-Sharp Minor – II. Andante (Thomas Martin, double bass; English Chamber Orchestra; Andrew Litton, cond.)

Following these two outstanding Italian bassists, Dragonetti and Bottesini, the Czech region saw a blooming of virtuoso bassists, including Franz Simandl, Theodore Albin Findeisen, Josef Hrabe, Ludwig Manoly, and Adolf Mišek.

In the 20th century, the famous conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Serge Koussevitzky, was a populariser of the double bass. One of the problems with the early double basses was that the cut strings they played on were heavy and unresponsive, and the pressure of the strings on the neck often meant that it was better to play with three strings (like Dragonetti) than the more normal four of the rest of the string section. With the use of steel strings, the double bass became more responsive, and more composers wrote for it. Koussevitzky’s 1902 Concerto for Double Bass was lost for many years as the composer kept the manuscript, and it was only found later. It received its original premiere in Moscow in 1905 before being lost.

Serge Koussevitzky and his double bass

Serge Koussevitzky: Double Bass Concerto, Op. 3 – I. Allegro (Entcho Radoukanov, double bass; Swedish Chamber Orchestra; Ronald Zollman, cond.)

The story behind Nino Rota’s fiendishly difficult Divertimento Concertante (1970) for double bass and orchestra starts with a double bass in a hotel room. Bassist Franco Petracchi was giving lessons in his hotel room with endless hours of scales and studies and driving the man in the next room mad. That was his friend Nino Rota who responded with his Divertimento Concertante, which contains numerous musical jokes and ‘maliciously difficult performance techniques’. At the same time, this is one of the outstanding modern pieces showing the instrument’s versatility.

Nino Rota: Divertimento concertante for Double Bass and Orchestra – IV. Finale: Allegro marcato (Bogusław Furtok, double bass; Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra; Peter Zelienka, cond.)

As a solo instrument, the double bass has a very limited repertory, but this is gradually improving. Austrian-American composer Lera Auerbach has written a number of works for solo double bass, including Memory of a Tango. This short piece resonates with sadness and melancholy.

Lera Auerbach: Memory of a Tango, Op. 64 (Dan Styffe, double bass)

As part of his long-running Strathclyde Concerto series, Scottish composer Peter Maxwell Davies wrote one for double bass. The Strathclyde Concerto No. 7 was given its premiere in Glasgow in 1992 by its dedicatee, bassist Duncan McTier. The orchestra has been made bottom-heavy to emphasize the lower registers and to provide the double bass with a ‘luminous backdrop’.

Peter Maxwell Davies: Strathclyde Concerto No. 7 – I. Moderato (Duncan McTier, double bass; Scottish Chamber Orchestra; Peter Maxwell Davies, cond.)

What’s bigger than a double bass? There is the rare Octobass. It was first built in Paris in 1850 by Jean-Baptist Vuillaume and is nearly double the height of a normal double bass. A double bass is about 2 meters (2’7”) tall while the Octobass is 3.48 (11’5”) tall. It weighs 131 kilos, so it’s rarely moved! Hector Berlioz was a fan of the instrument.

Eric Chappell of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra playing the orchestra’s octobass

There are copies of the octobass in Paris, Vienna, and Phoenix, Arizona, in various musical instrument museums and a couple in private collections. The Montreal Symphony, however, is the only orchestra in the world with an octobass as a member of the orchestra. As you can see in the image of the octobass, there’s no way for the player to reach the fingerboard. At the musician’s foot is a system of levers and pedals that press on the strings to make the right note. The performer bows the strings and then uses the levers for the correct notes.

Later models, also developed by the same luthier who made the Montreal instrument, include a keyboard in the curve of the instrument that uses motors to operate the string stops and is much easier to use than the lever model.

An Octobass

In 2020, the Montreal Symphony was able to bring 3 octobasses together for a concert.

February 2020, Three octobasses in performance with the Montral Symphony Orchestra

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter