We primarily remember Dinu Lipatti as a celebrated and exceptional pianist. For Yehudi Menuhin, he was “a manifestation of a spirit realm, resistant to all pain and suffering,” while Alfred Cortot considered his playing “quite simply perfection.” And Francis Poulenc called Lipatti “an artist of divine spirituality.”

Dinu Lipatti

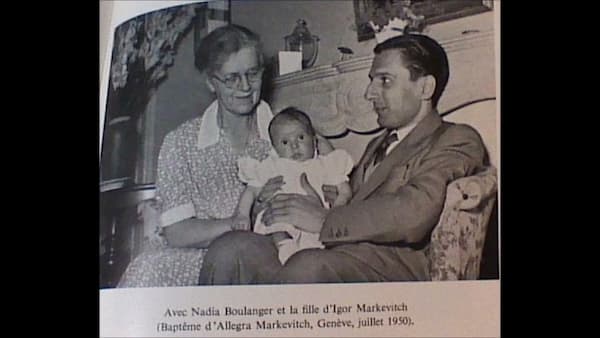

Lipatti, however, was not merely an exceptional pianist; he was also a highly talented composer. Cortot had invited him to study in Paris, and he took piano lessons with Yvonne Lefébure and studied composition with Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger. Boulanger was haunted by “that serene face with its dark velvet eyes and the musical force and clarity that emanated from him.” In turn, Lipatti called her his “musical guide and spiritual mother.”

Lipatti’s compositional output is relatively small due to his short life (1917-1950), but according to scholars, “it is marked by elegance, technical precision, and emotional depth.” Plenty of reasons, it seems to me, to unveil Lipatti the creative artist by featuring some of his most outstanding compositions.

Dinu Lipatti: Piano Concertino in the Classical Style, Op. 3 (Marco Vincenzi, piano; Padua and Veneto Chamber Orchestra; Gert Meditz, cond.)

Sinfonia Concertante for Two Pianos and String Orchestra

Dinu Lipatti and Alfred Cortot

The Sinfonia Concertante for Two Pianos and String Orchestra dates from 1938 and was written during his time in Paris. Composed at the age of 21, Lipatti had been establishing himself as both a performer and a composer, and the first performance took place on 10 May 1939. Ionel Perlea conducted, and Lipatti and Clara Haskil, a renowned pianist with whom he shared a close artistic affinity, performed the demanding solo piano parts.

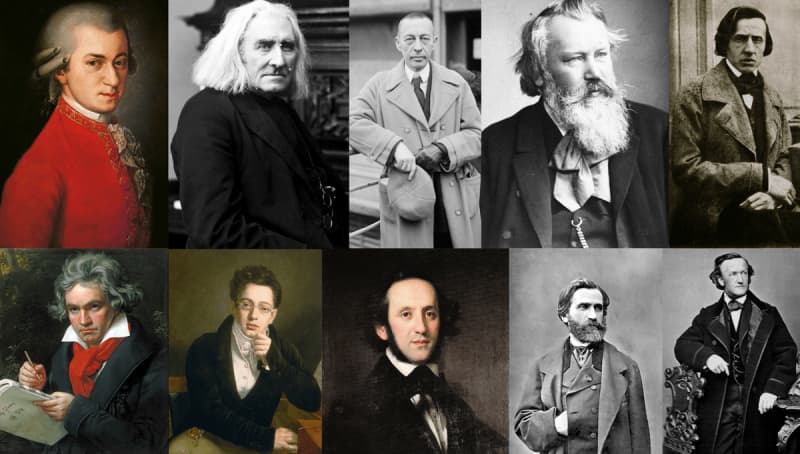

To scholars, the choice of the sinfonia concertante form, a hybrid of symphony and concerto popular in the Classical era, “reflects Lipatti’s admiration for the music of Mozart.” It also reflects the neoclassical trends of the early 20th century as championed by Stravinsky and Ravel. Lipatti infuses this traditional framework with a modern harmonic language and a dynamic interplay between the two pianos and the string orchestra.

Harmonically, the work straddles the line between tonality and modernity, as a clear tonal centre is enriched by chromatic detours and unexpected modulations. In addition, his use of counterpoint is particularly striking, reflecting his study of Bach and his ability to adapt Baroque technique to a 20th-century context. It is a vibrant and expertly crafted piece that reflects both his prodigious talent and his deep connection to musical traditions.

Fantasie for Piano, Op. 8

Composed and dedicated to Madeleine Cantacuzène, a fellow pianist whom he married in 1948, the Fantasie Op. 8 is his “longest and most complex solo piano composition.” Probably composed during the early 1940s, this masterpiece is structured as a free-form fantasy unfolding in a five-movement continuous narrative. The harmonic language blends tonal clarity with subtle chromaticism in a synthesis of his training under Boulanger and Dukas.

The clarity of textures “speaks for themselves in exploratory and often heartfelt simplicity.” It certainly features folk-music elements that gently point towards Bartók, but “this is music with an intrinsic and individual quality, filled with fascinating nuance.” Lipatti avoids radical experimentation in favour of a refined, accessible style, while he exploits the full range of the piano from crystalline treble lines to resonant basses.

Nadia Boulanger would write, “When the compositions of Dinu Lipatti are all printed, the greatness of his gift and his craftsmanship will be recognised. It will become obvious that he was really a composer who found his pleasure and his real life in the process, and who used the technical means of his art to create the emotions resulting from achieved beauty.”

Dinu Lipatti: Fantasie for Piano, Op. 8 (Sontraud Speidel, piano)

Nocturnes

Dinu Lipatti

Dinu Lipatti composed two nocturnes for solo piano, and unlike his more structurally ambitious pieces, these nocturnes highlight his ability to craft intimate and atmospheric music rooted in the Romantic tradition. While the Nocturne in A minor, also known as “Nocturne on a Moldavian Theme”, was probably composed somewhere between 1937 and 1939, the Nocturne in F-sharp minor dates from between 1941 and 1942.

The Nocturnes emerged during a pivotal phase of Lipatti’s life. The A minor was written while he was in his early twenties, studying and performing in Paris. At that time, he was immersed in the cosmopolitan musical scene under the guidance of Boulanger and Dukas. The F-sharp minor, meanwhile, was composed a couple of years later, during World War II. At that time, Lipatti had initially returned to Romania and was navigating the challenges from his emerging illness.

Dinu Lipatti: Nocturne in A minor (Marco Vincenzi, piano; Padova e del Veneto Orchestra; Gert Meditz, cond.)

The Nocturne in A minor blends Romanian folk influences with a refined pianistic style. Apparently, it takes us into the atmosphere of Christmas Eve, as “a sort of improvisation on a ‘Colinda’, a Moldavian Christmas carol. Blending French harmonies and timbres, Lipatti evokes a quiet and nocturnal landscape. Some critics hear the influence of his godfather, George Enescu, as the bittersweet and nostalgic qualities tie this nocturne to its folk origins. The slightly faster and more agitated contrast returns us to the initial theme, now imbued with deeper resonance.

The F-sharp minor Nocturne, with its frequent ostinato passages, seemingly recalls the Nocturnes by Gabriel Fauré. In addition, it clearly draws inspiration from Chopin while incorporating Lipatti’s unique sensibility. The melody is not explicitly folk-based, but carries his signature long and arching phrases that unfold with natural grace. This nocturne feels more personal and sombre, possibly reflecting his illness and the wartime backdrop. It balances melancholy with moments of serene beauty, ending in a quiet and contemplative resolution.

Dinu Lipatti: Nocturne in F-sharp minor (Marco Vincenzi, piano; Padova e del Veneto Orchestra; Gert Meditz, cond.)

3 Romanian Dances

Dinu Lipatti with Nadia Boulanger

In his set of Romanian Dances, originally composed for two pianos around 1937, Lipatti fuses contemporary sonorities with Romanian folk rhythms. He showcases his deep connection to Romanian musical traditions by uniquely blending his national heritage with neoclassical refinement. Initially composed for two pianos, he later orchestrated the dances for piano and orchestra. This dual existence, according to a scholar, “highlights the work’s versatility and Lipatti’s practical approach as a performer-composer.”

The Romanian Dances are steeped in the rhythms and modes of Romanian peasant music, as distinct from the urbanised “lăutărească” gypsy fiddler style. Yet despite their folk roots, the dances are tightly structured, with clear thematic developments and balanced proportions. In the featured version for two pianos, the music creates a conversational texture, “simulating the communal nature of folk dance while exploiting the full range of the instruments.”

The set moves from exuberance to introspection to triumph, conveying varied moods within a concise form. Published posthumously, the Romanian Dances are a spirited celebration of Lipatti’s Romanian heritage, crafted with neoclassical precision and pianist brilliance. According to commentators, “they offer a vivid snapshot of a composer whose voice was silenced too soon.”

5 Chansons de Paul Verlaine, Op. 9

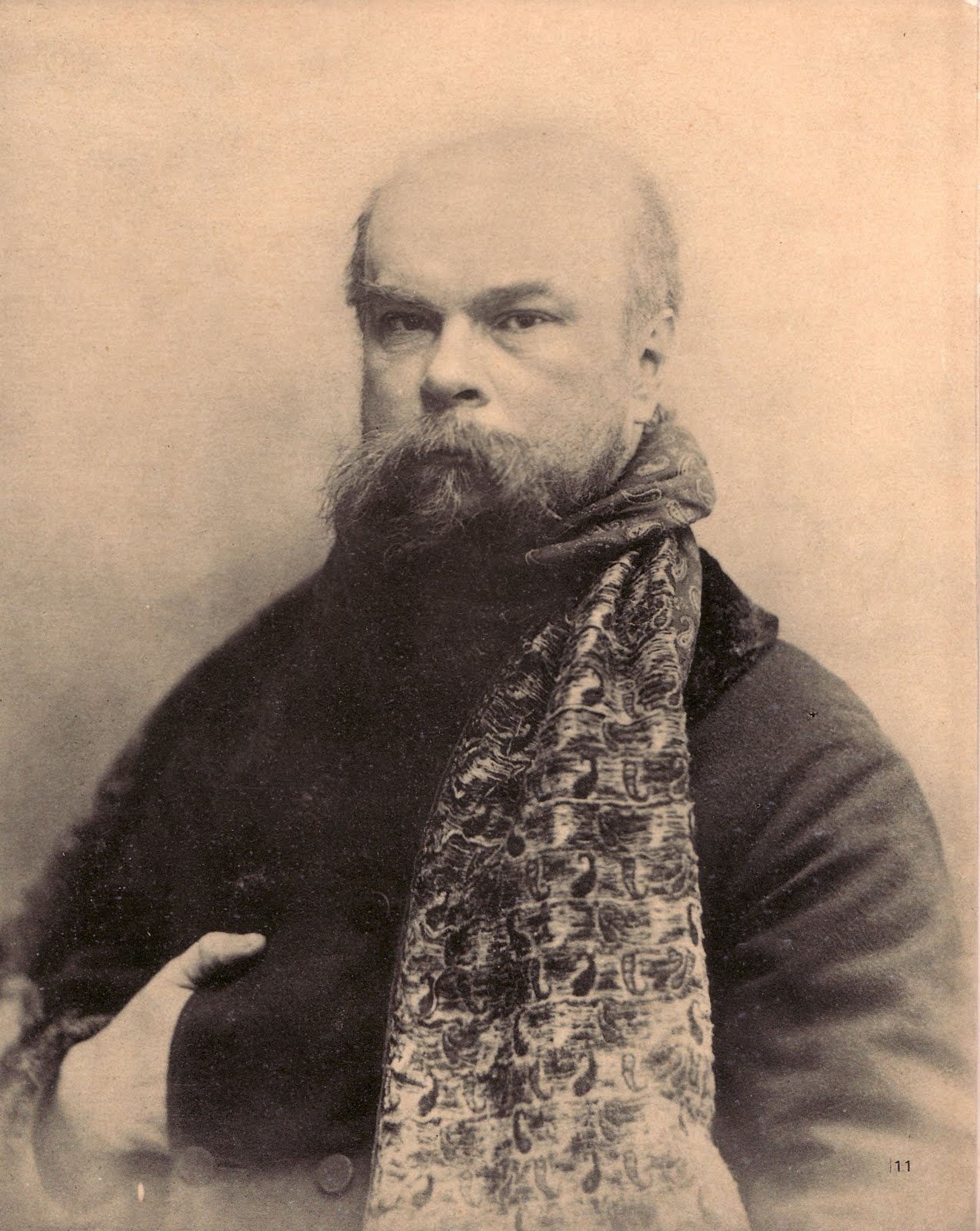

Paul Verlaine

Dinu Lipatti’s Cinq Mélodies sur des Poèmes de Paul Verlaine dates from between 1941 and 1945. Reflecting his affinity for the French musical tradition, this set of art songs for tenor and piano was shaped by his time in Paris and his admiration for Paul Verlaine. It was composed during a period of personal and global challenges, as Lipatti had fled Romania in 1941 and eventually settled in Geneva, Switzerland. He taught at the Geneva Conservatory while battling the early stages of Hodgkin’s disease.

This set was begun in Romania and completed in Geneva, with multiple revisions in between that reflect the interruptions by war and exile. The cycle is dedicated to the Swiss tenor Hugues Cuénod, a personal friend and collaborator. According to scholars, “Verlaine’s evocative musical poetry, rich with imagery and emotional ambiguity, provided the ideal canvas for Lipatti’s lyrical and refined style.”

In his five Verlaine settings—initially, he had planned for six songs—Lipatti blends French Impressionist influences with neoclassical clarity and subtle Romanian undertones. The elegant vocal lines and impressionistic piano textures, focusing on poetic nuance, were surely shaped by his studies with Boulanger and Dukas. The idiomatic and expressive piano parts, tailored to his own virtuosic yet poetic touch, serve as equal partners to the voice. The set fuses Verlain’s Symbolist poetry with a refined neoclassical style, offering a delicate yet profound addition to the French mélodie repertoire.

Dinu Lipatti: 5 Chansons de Paul Verlaine, Op. 9 (Markus Schäfer, tenor; Mihai Ungureanu, piano)

Sonatina for the Left Hand

Dinu Lipatti in 1946

The Sonatina for Piano, for left hand alone, was written and dedicated to Ion Filionescu, a Romanian pianist and friend who had lost the use of his right hand. It fits into a tradition of left-hand piano works from that time, such as those commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein from Ravel, Strauss, Prokofiev, and many others.

The single-movement composition reflects Lipatti’s ability to create expressive music within a constrained medium. It is a buoyant and optimistic work, with its playful opening denying its wartime origin. Echoing the clarity and economy of his neoclassical style, the piece avoids sentimentality but blends light-hearted energy with moments of poignant lyricism. It is a small but brilliant gem in his tragically brief legacy.

Dinu Lipatti’s legacy as a composer, though overshadowed by his extraordinary pianistic career, reveals a remarkable talent whose works blend neoclassical precision, Romanian folk influences, and a profound lyrical sensibility. Limited by a brief life and a focus on performance, his output remains small yet impactful, offering a tantalizing glimpse of a creative potential cut short.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Dinu Lipatti: Piano Sonatina (for the left Hand) (Marco Vincenzi, piano)