Frédéric Chopin was one of the most influential classical musicians of the nineteenth century.

Many composers clamored to dedicate their own work to Chopin as a sign of their admiration and respect. Even after his death, composers still dedicated works to him!

Today we’re looking at the stories behind seven pieces of music dedicated to Chopin.

Frédéric Chopin © Hadi Karimi

Ferdinand Hiller: 3 Caprices, Op. 14 (1834)

Composer Ferdinand Hiller (1811-1885) was born in Frankfurt, Germany. He was a child prodigy who made his concerto debut at the age of ten playing a Mozart piano concerto.

Hiller wove in and out of the lives of many of the nineteenth century’s greatest composers.

When Hiller was eleven, he befriended the seventeen-year-old Fanny Mendelssohn and her thirteen-year-old brother Felix. The Mendelssohns and Hiller were dear friends for decades.

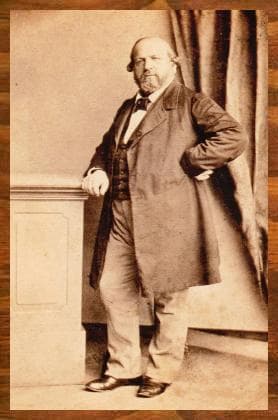

Ferdinand Hiller

Later, when he was sixteen, he was studying with composer Johann Nepomuk Hummel when Hummel brought him to Beethoven’s death bed. Hiller saved a lock of Beethoven’s hair. While in Vienna, he saw Schubert play the piano part during a performance of Winterreise.

He lived in Paris in the late 1820s and early 1830s, and befriended Chopin and many other Paris-based composers during that time. In 1834, Chopin dedicated the three nocturnes from his op. 15 to Hiller, and Hiller responded by dedicating three caprices to Chopin.

Chopin: Nocturnes, Op. 15: No. 1 in F Major (Andante cantabile)

Robert Schumann: Kreisleriana (1838)

Schumann and Chopin met twice.

The first time was in 1835. Chopin had been visiting his parents, and on the way home, he stopped to visit Schumann in Leipzig. Schumann journaled about the meeting, but no record exists of Chopin’s impressions of him. Robert’s future wife Clara also played for Chopin; although she was only sixteen at the time, she was an internationally renowned pianist who championed his works.

Chopin and Schumann met again in 1836. Schumann wrote to Chopin to ask if he’d be interested in visiting during his travels; Schumann never got a response, but he did come home one day to find Chopin waiting at his door! Again, the two played their works for each other, and again, we have a record of Schumann’s excitement about the visit, but nothing from Chopin’s perspective.

Robert Schumann, 1839

The two dedicated works to each other. In 1838, Schumann dedicated his piano work Kreisleriana to “To my friend, Mr F. Chopin.” Two years later, Chopin responded by dedicating his Ballade in F-major to “Mr Robert Schumann”…a dedication that lacked the enthusiasm of Schumann’s.

Édouard Wolff: Grand allegro de concert, Op.39 (c. 1840)

Édouard Wolff was born in 1814 in Warsaw, four years after Chopin.

Wolff studied piano in both Warsaw and Vienna before leaving for Paris in 1835, where his career took off. (Incidentally, after he became established, he helped to advance the career of his nephew, violin virtuoso Henryk Wieniawski, who was born the year that Édouard departed for Paris.)

By the end of Wolff’s long career, he had written over three hundred and fifty works.

Wolff’s “Grand allegro de concert” featured a number of blatant stylistic references to Chopin, and Wolff dedicated it to him.

Friedrich Kalkbrenner: Causerie de jeune fille, Op. 128 No. 3 (1845)

Composer and pianist Friedrich Kalkbrenner was born in 1784 in, as legend has it, a mail carriage on a road outside Berlin.

He was a child prodigy who studied at the Paris Conservatoire and later in Vienna. He became enormously wealthy by giving concerts and starting a successful piano academy.

Friedrich Kalkbrenner

In 1831, Chopin considered studying with Kalkbrenner, but Kalkbrenner was going to insist they spend three years together, and Chopin was hesitant to commit. Nevertheless, as Chopin’s career blossomed, in part due to Kalkbrenner’s promotion, the two men remained friendly colleagues.

In 1845 Kalkbrenner wrote this brief piano piece and dedicated it to Chopin. Translated into English, the title means “Young girl’s gossip.”

Adolf Gutmann: Dix Etudes (1848)

Adolphe Gutmann was a German composer who was born in Heidelberg in 1819.

When he was fifteen, he moved to Paris to study with Chopin, and soon became one of Chopin’s favorite students. As tribute, Chopin dedicated his Scherzo No. 3 in C-sharp minor to Gutmann in 1839.

Gutmann and Chopin stayed friends into Gutmann’s adulthood. In 1848, Gutmann dedicated his 10 Etudes to Chopin, who by this time was very sick with tuberculosis and clearly nearing the end of his life.

In October 1849, Chopin died. Gutmann visited Chopin’s deathbed and even saved the glass that Chopin took his last drink of water from.

Stephen Heller: Élégie et Marche funèbre, Op.71 (post-1849)

When Chopin died, many musicians were devastated at the loss of their colleague. One such was Hungarian composer Stephen Heller.

Heller was born in 1813 in Pest. As a child, he moved to Vienna to study under Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny.

In the late 1820s, like so many other great pianists and composers of his generation, he moved to Paris. While there, he became friends with Chopin.

This unusual piano work was written as a response to Chopin’s death. It begins with extensive quotations from the melancholy Prelude No. 4 in E-minor, and gradually evolves into a sorrowful elegiac reimagining of Chopin’s original work. Later in the score, Heller includes music from Chopin’s Prelude No. 6 in B-minor.

Claude Debussy: Etudes (1915)

Chopin’s life, music, and early death resonated for decades after his passing.

French composer Claude Debussy was deeply inspired by Chopin. He once said, “Chopin is the greatest of all. For with the piano alone he discovered everything.”

Debussy paid the ultimate artistic tribute to Chopin by dedicating a set of twelve etudes to him, all written in the summer of 1915 during World War I. Debussy wrote that they were “a warning to pianists not to take up the musical profession unless they have remarkable hands.”

Nadar: Debussy 1908

Different etudes cover different technical challenges: playing in thirds, playing in fourths, playing in sixths, playing in octaves, playing ornaments, and playing chords, among other skills.

Debussy died a few years after these etudes were written, and they’re considered to be some of Debussy’s last masterpieces: a fitting tribute to the inescapable influence of Frédéric Chopin.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter