The process of adapting a piece of music for a scoring other than that of the original dates back for centuries. For one, by fashioning transcriptions and arrangements of orchestral works or operas, the public gained access to the latest and hottest musical items on the market. And secondly, the traveling virtuoso frequently used transcriptions of well-known compositions to impress audiences with unsurpassed virtuosity and showmanship.

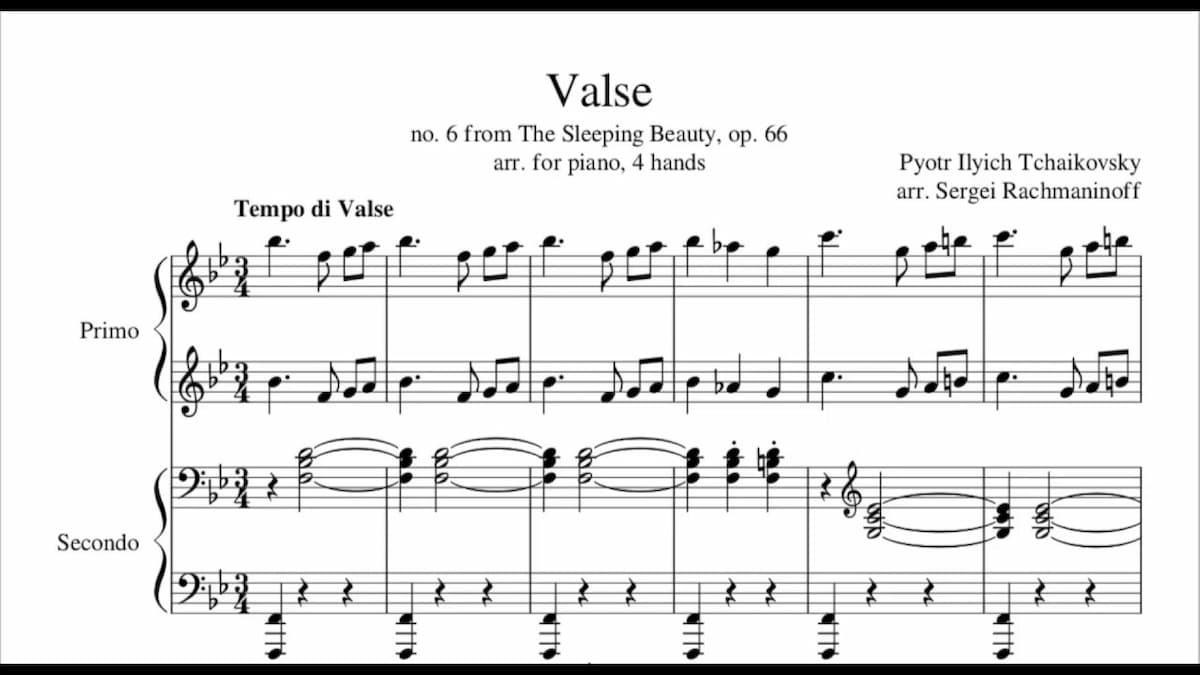

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky: The Sleeping Beauty, (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano 4 hands)

Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty arranged by Rachmaninoff

The first attempts by Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) probably date from his early years at the Conservatory and produced a piano duet arrangement of Tchaikovsky’s “Manfred Symphony.” That student exercise appears to have been lost, but Tchaikovsky officially commissioned Rachmaninoff in 1891. Soon after the premiere of The Sleeping Beauty, Tchaikovsky and his publisher Jurgenson were looking for a piano arrangement of the ballet for four hands. In the end, the assignment was given to the 18-year-old Rachmaninoff.

Tchaikovsky, however, was really disappointed as he felt the arrangement “lacked in courage, initiative, and creativity!!!” Tchaikovsky added, “I wanted the ballet to be arranged for four hands so that it might be rendered as seriously and skillfully as an arrangement of a symphony. Alas, this is impossible; what has been done cannot be undone; but at least it will be an improvement on what we have now.” Despite all protestations, the Rachmaninoff piano duet arrangement of The Sleeping Beauty was published in October 1891.

Alexander Glazunov: Symphony No. 6, “II. Tema con variazioni” (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano 4 hands)

Sergei Rachmaninoff

On the evening of 15 March 1897, the Hall of the Nobility in St. Petersburg saw the world premiere of two symphonies. The symphonies on offer were Alexander Glazunov’s Sixth Symphony and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s First, both works conducted by Glazunov himself. Glazunov’s symphony scored a resounding triumph, whereas Rachmaninoff’s work was declared a complete failure. The critic and nationalist composer César Cui likened the work to a depiction of the seven plagues of Egypt and suggested that it “would only be admired by the inmates of a music conservatory in Hell.” As is well known, Rachmaninoff fell into a depression that lasted the better part of three years.

Alexander Glazunov: Symphony No. 6, “II. Tema con variazioni” (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano 4 hands) (Dag Achatz, piano; Yukie Nagai, piano)

Franz Behr: Lachtäubchen, Op. 303, “Polka de W. R.”

The relationship between Rachmaninoff and Glazunov did not end with this memorable performance, however, as the Belyayev publishing house commissioned an arrangement from Rachmaninoff of the Glazunov Symphony. In November 1897 Glazunov writes, “I have not yet had time to write and thank Rachmaninoff for doing the arrangement,” which probably indicates that Glazunov approved of Rachmaninoff’s efforts. Transcribing orchestral works for piano can be a thankless task, but Rachmaninoff successfully recreates the orchestral sound on the keyboard. A scholar writes, “While remaining essentially faithful to the original, it uses sparse figures for a more pianistic effect in a number of places.” Arrangements of orchestral scores brought that music into salons and affluent households, but Rachmaninoff’s piano transcriptions formed an attractive and popular element in his recitals. Franz Behr (1837-1989) was a popular German composer of songs and salon pieces for piano in his day. Today he is almost completely forgotten, except for Rachmaninoff’s transcription of his “Lachtäubchen,” Op. 303. Apparently, the tune was a favourite of Rachmaninoff’s father Vassily, as the “W. R.” in the title refers to his father’s initials. The arrangement dates from 24 March 1911, and it is dedicated to the virtuoso pianist Leopold Godowsky. For the longest time it was believed that the tune was an original work by Rachmaninoff, and only recently has the true composer of the melody been identified.

Franz Behr: Lachtäubchen, Op. 303, “Polka de W. R.” (Idil Biret, piano)

J. S. Bach: Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano)

Rachmaninoff’s transcription of Bach’s Violin Partita

There was no problem with name recognition when Rachmaninoff arranged three movements from the third violin partita by Johann Sebastian Bach for solo piano in 1933. A commentator wrote, “With a few exceptions, Rachmaninoff was generally quite faithful to the source music in his transcriptions. In this Bach effort, however, he added contrapuntal parts and harmonies because the original was written for solo violin.” Rachmaninoff completely rethought the three movements “for the keyboard with an almost disconcerting completeness… It is very much in the distilled manner of Rachmaninoff’s later keyboard writing, and one regrets that he did not make paraphrases of other movements from the Partita.” Rachmaninoff gave the first performance of the three movements early in his 1933/4 Season at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and they were published that same year. Not everybody was delighted, and Rachmaninoff came under attack by “assorted puritans and pseudo-intellectuals, particularly as the fashion of confining baroque keyboard music to the harpsichord was then intensifying.”

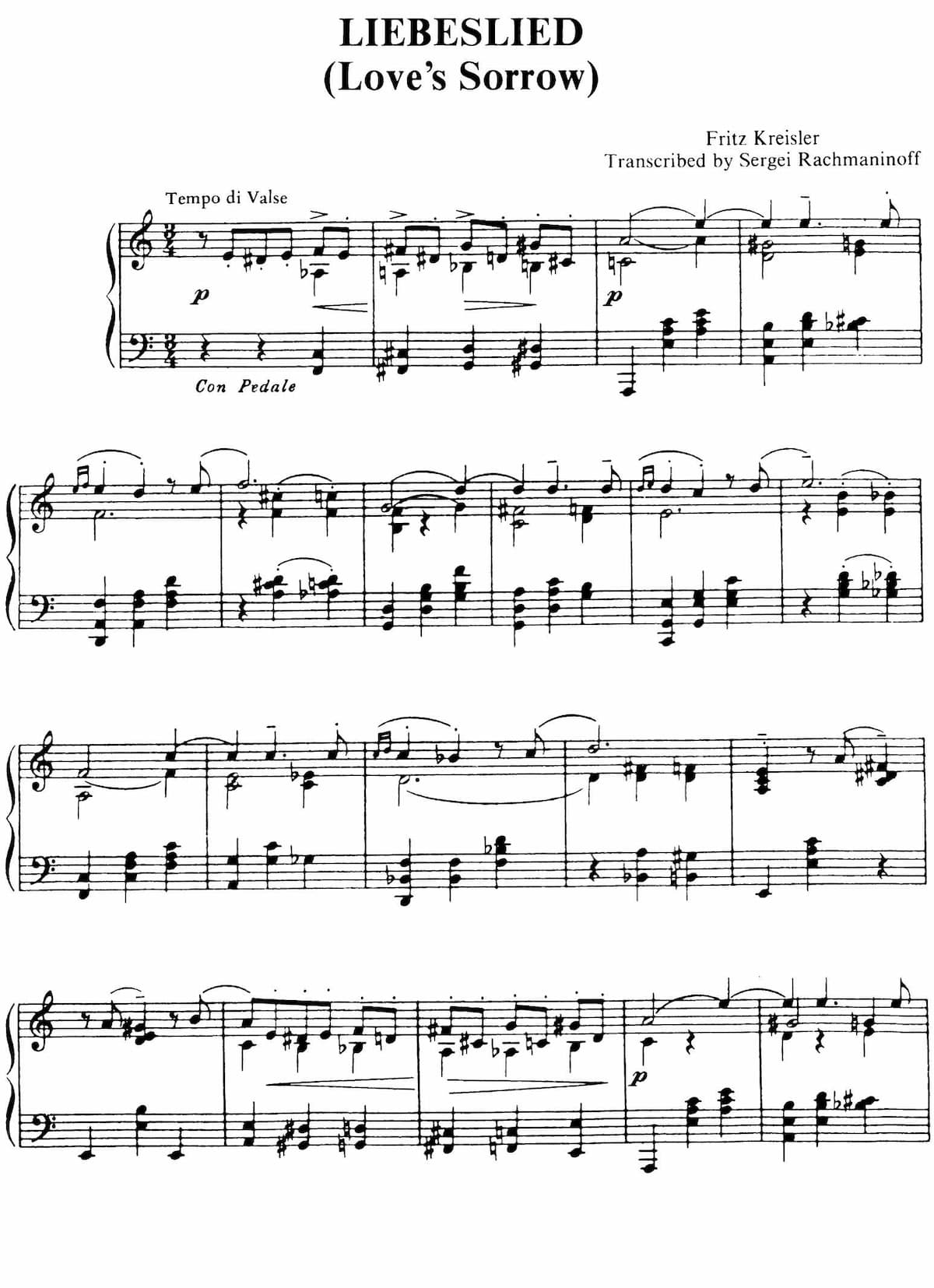

Fritz Kreisler: Liebesleid, (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano)

Fritz Kreisler’s Liebesleid arranged by Rachmaninoff

A funny anecdote tells of Rachmaninoff giving a recital in New York with violinist Fritz Kreisler. Somehow, Kreisler lost his place in the music, and panic stricken whispered to Rachmaninoff, “Where are we?” The reply came back promptly, “Carnegie Hall.” Rachmaninoff had arrived in New York in November 1918, and he was warmly welcomed by a number of distinguished musicians, including Fritz Kreisler. They quickly became close friends and started to perform together. In addition, they also collaborated in the studio on three occasions with joint recordings of Beethoven’s Eighth Violin Sonata, Grieg’s Third Violin Sonata, and Schubert’s Grand Duo (Sonata) for violin and piano. In addition, Kreisler had produced a transcription of Rachmaninoff’s “Daisies,” and in 1925 and again in 1931, Rachmaninoff transcribed two works by Kreisler. As a tribute to their friendship, Rachmaninoff created piano arrangements of the Kreisler violin miniatures “Liebesleid” (“Love’s Sorrow”), and “Liebesfreud” (“Love’s Joy”). Kreisler’s original compositions are charming slices of pre-war Vienna, and in Rachmaninoff’s hands they become thrilling new music infused with unexpected harmonic twists and turns, and a sparkling virtuosity in fast passages.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, No. 2 “Wohin?” (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano)

Rachmaninoff had a profound understanding of compositional and pianist devices. As such, his transcriptions are not only unique in sound and brilliance but also supremely expressive. Part of this expressiveness is realized through his own complex and distinctive harmonic language. In addition, counterpoint plays a substantial role in all his transcriptions. As a pianist writes, “from a performance point of view, important features of Rachmaninoff’s approach are contained in the composer’s use of acoustical qualities of the instrument and the factors that influence the aural perception of a melodic line and its elements. In the juxtaposition of melodic elements, Rachmaninoff frequently places a main melodic line, already familiar to the listener, in the highest register within the texture. Both factors of repetition and registration aid the aural perceptibility of the melodic line.” Rachmaninoff’s arrangement of Schubert’s song “Wohin,” from Die Schöne Müllerin dates from 1925, the year of the sudden death of his son-in-law. The song becomes a splendid example of the transcriber’s art, preserving, with the most delicate of additions, the full flavor of the original.

Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin, No. 2 “Wohin?” (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano) (Idil Biret, piano)

John Stafford Smith: “The Star-Spangled Banner,” (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano)

Star-Spangled Banner arranged by Rachmaninoff

Rachmaninoff came to the United States in 1918, but he was Russian to the core. Although born into an aristocratic family in Russia, he spent the last years of his life in Beverly Hills, California. When the “Great Patriotic War” broke out in 1941, Rachmaninoff donated at least four thousand dollars to finance building combat aircraft. He also called on Russian emigrants abroad to unite their efforts and help the Soviet Union in its fight against fascism, for which he even earned the nickname “Red Rachmaninoff.” He only accepted U.S. citizenship in 1943, the year of his death, and said, “This is the only place on earth where a human being is respected for what he is and what he does, and it does not matter who he is and where he came from.” Rachmaninoff the pianist was keenly aware of the demands placed upon him by his American audiences. Every recital had to feature a version of the patriotic Star Spangled Banner, and unsurprisingly, Rachmaninoff provided a version in 1918. Fortunately, Rachmaninoff recorded all of his transcriptions, and his Star Spangled Banner provides a melancholy soundscape without rocketing flares and glittery bombast.

Felix Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “Scherzo” (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano)

For Rachmaninoff, the act of transcribing was a satisfying compositional experience rather than a pure exercise in piano reduction technique: As he writes, “During my summer rests from the fatigue of my tours as a pianist, I return to composition. My last works were transcriptions for piano of a work by Bach and the “Scherzo” from Mendelssohn’s music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” The Mendelssohn transcription was crafted in 1933 and heard by London audiences in April of that year. A scholar writes, “seldom has the spirit of an orchestral showpiece been applied to the piano as effectively… considerable ingenuity is exercised to suggest the constant repeated sixteenth notes of the winds without actually copying them.” Rachmaninoff’s transcriptions are “fiendishly difficult works with their luxuriant harmonies, rhythmic subtleties, and contrapuntal lines that can tangle the most nimble fingers.” And an eminent pianist writes, “the transcription of Mendelsohn’s “Scherzo” is a real finger twister, reserved only for spectacular virtuosos.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Rachmaninoff was not only one of the great composers, he was probably the

greatest keyboard performer after J.S Bach.