For a number of commentators, Arnold Bax is far and away the most neglected British composer who flourished in the first half of the 20th century. Composing during a time that, say, the likes of Elgar and Britten, Delius and Holst, Vaughan Williams and Walton, Bax got somehow lost in the shuffle. It certainly did not help public recognition that Bax was intensely shy and retiring and did little to promote his own music.

Arnold Bax: Quintet for Oboe and Strings

Ancestry and Parents

Arnold Bax was born at Heath Villa, Angles Road, Streatham, on 8 November 1883 to Alfred Ridley Bax and his wife Charlotte Ellen Bax nee Lea. The Bax ancestry traces back to Holland and the 16th century, but they had established a base in the Ockley district of Surrey. They rose to wealthy middle-class status, generating income from the manufacture of Mackintosh raincoats, and Alfred Bax also dabbled in property development. He was a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, collected brass rubbings, and “was a mild-tempered man who left the running of the household and all domestic matters to his wife.”

Arnold Bax

Charlotte Ellen Bax was the daughter of a Congregationalist minister and one-time missionary to China, where she was born in 1860. Almost 20 years younger than her husband, Charlotte was described as “A sweet and lovable woman,” and her “dominant influence over her children shaped their characters and latent talents.” She was described as full of vitality, highly sexed, and anxious to gain some respectability in her social life. The couple had four children and appointed a tutor to look after the education of their sons Arnold and Clifford.

Arnold Bax: Toccata (Eric Parkin, piano)

Early Education

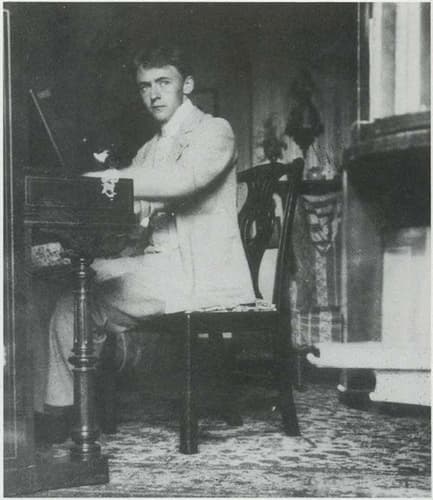

Arnold Bax at the piano, 1901 © Graham Parlett

Arnold’s early schooling was unremarkable, but he apparently made a name for himself on the cricket field. Francis Colmer, an eccentric exhibitioner from Exeter College, Oxford, was hired as a tutor, and he possessed a “great deal of general knowledge, but more especially of books and paintings, and he was pathetically short-sighted.” He keenly assessed the growing character of his charges by writing, “Both Arnold and Clifford had an undeniable feminine streak, which they certainly derived from their mother.”

Arnold had no formal musical education before 1898, but he later wrote in life that he was unable to remember a time when he could not play the piano or was unable to manage at least a “miserable smattering” of French. His father began taking him to the Crystal Palace Saturday concerts, and “Arnold amused himself for hours by improvising absurd symphonies and overtures from the musical excerpts printed in the playbills.” Arnold’s father was part of a private choral society, and the young pianist acted as accompanist from about the age of 13. It was around that time that Arnold started to compose.

Arnold Bax: A Romance (Eric Parkin, piano)

At the Royal Academy of Music

Arnold Bax’s sister and mother © Graham Parlett

These early attempts convinced his father that Arnold should seek professional instruction, and he was enrolled at the Hampstead Conservatoire. He made good progress in his piano studies, and his earliest surviving compositions are all tied to the piano. We find minuets, Hungarian dances, and strongly influenced a couple of Nocturnes in the style of Chopin. In 1900, Bax became a student of the Royal Academy of Music.

Bax studied composition with Frederick Corder and piano with Tobias Matthay. Corder was a devotee of the works of Wagner, and he was the author of one of the first English-language studies of Liszt. Bax remembered later, “for a dozen years of my youth, I wallowed in Wagner’s music to the almost total exclusion of any other.” However, the influences of Tchaikovsky and Glazunov are reflected in his piano music, and Bax discovered and privately studied the works of Debussy.

Arnold Bax: Clarinet Sonata in E Major (Robert Plane, clarinet; Benjamin Frith, piano)

Various Romances

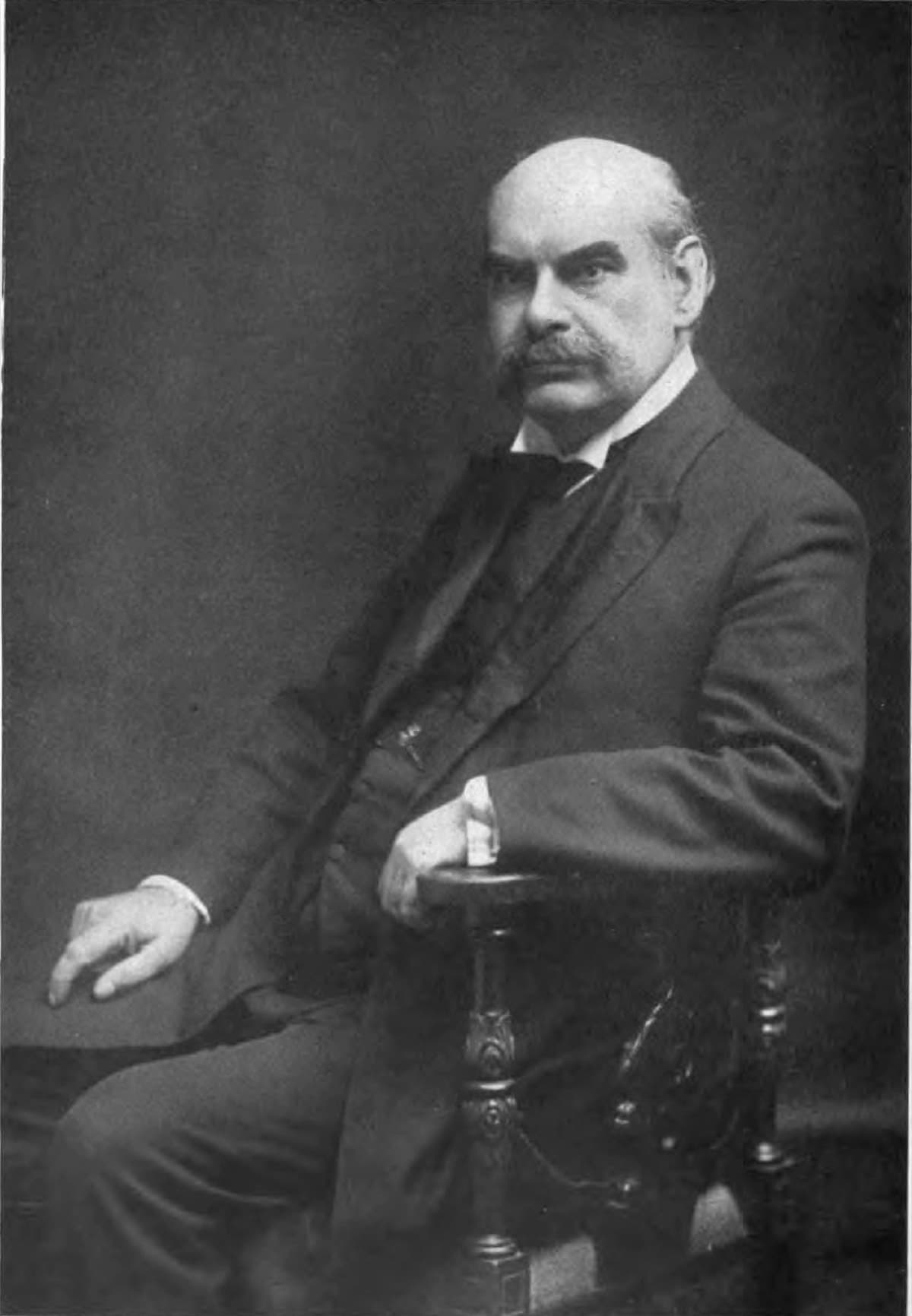

Frederick Corder

There is still a good deal of discussion as to how much Bax learned from Corder. Corder was highly thought of by many commentators, but none of his students achieved more than short-term notoriety. It has been suggested that Corder “influenced Bax much less than any of his other students.” As Bax wrote to Edward J. Dent in the early 1920s, “Corder had no sympathy with vague rhapsodising. As a matter of fact, he was of course, an arch-Wagnerian and anti-Brahmsite and had very little sense of symphonic form and none of orchestration.”

Bax continued to write music and very gradually found his way forward. He slowly began to produce scores with growing contrapuntal and harmonic complexity, and his countless college romances “during the five years of his formal musical education found their way into a number of scores.” In fact, Bax was particularly smitten with student violinist Gladys Lees, and his relationship with her eventually developed into his first serious love affair. Bax completed his first successful attempt at a large-scale orchestral work, his Variations for Orchestra, in 1904. It won the RAM’s composition prize, but was not publicly performed. After leaving the Academy, Bax visited Dresden and first heard the music of Mahler, which he found “eccentric, long-winded, muddle-headed, and yet always interesting.” Bax subsequently turned his attention towards Ireland and began to forge his mature musical style.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Arnold Bax: A Celtic Song Cycle, “To Eire” (Ailish Tynan, soprano; Iain Burnside, piano)