Once he had reached the age of 75, Gabriel Fauré retired as head of the Paris Conservatoire in October 1920. He was excited to finally have the time to devote himself entirely to composition, and “produced a series of works that crown his whole output: the Second Cello Sonata, the Second Piano Quintet, the song cycle L’horizon chimérique and the Nocturne No.13.”

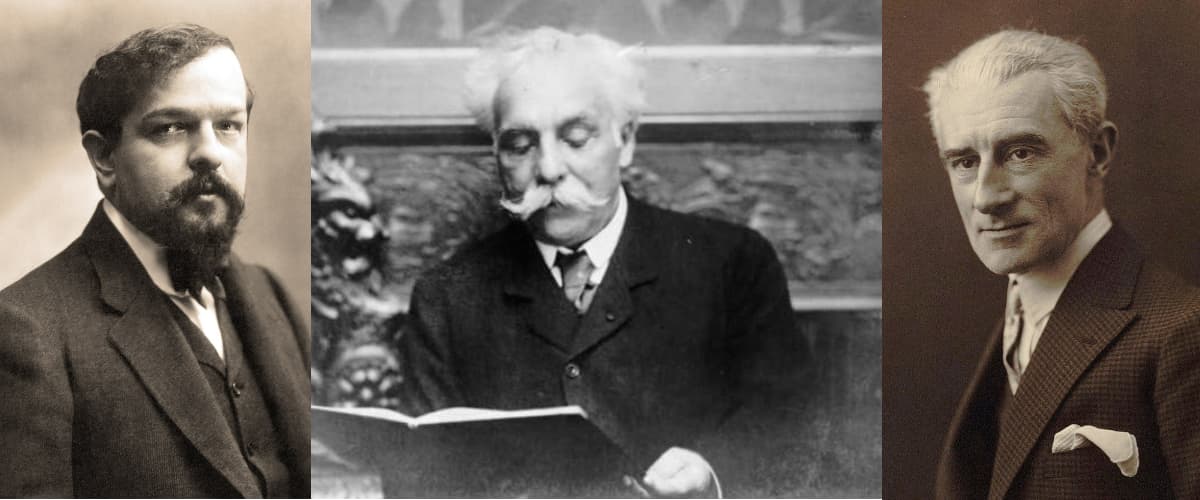

French composers: Claude Debussy, Gabriel Fauré and Maurice Ravel

However, within a couple of years after his retirement his health started to decline and he experienced symptoms of sclerosis, difficulty breathing brought on in part by decades of heavy smoking, and loss of hearing. During 1922 and 1923 he spent long months in his room, with his creative faculties intact, but he was easily tired. Fauré remained available to younger composers, including member of Les Six, and his biographer Jean-Michel Nectoux reports, “in old age Fauré attained a kind of serenity, without losing any of his remarkable spiritual vitality, but rather removed from the sensualism and the passion of the works he wrote earlier.” In his final composition, the String Quartet Op. 121 completed in 1924, the composer turned away from his favorite instrument and instead wrote music for the prototypical ensemble genre of Classical Music. “I’ve started a quartet for strings, without piano,” Fauré wrote to his wife. “This is a genre made particularly famous by Beethoven, so that anyone who is not Beethoven is scared stiff of it!”

Gabriel Fauré: String Quartet in E minor, Op. 121

While Fauré had always admired the music of Beethoven, he was not that charitable towards some of his contemporaries. As he writes to his wife, “The excessive polyphony of Wagner, the chiaroscuro effect of Debussy, the vulgar, impassioned writhing of Massenet are the only things that move or attract the attention of the general public. Yet the clear and consistent music of Saint-Saëns, to which I myself feel most attracted, leaves this same public indifferent. And all that sort of thing gives me a pain in the neck.” And when he listened to the premiere of Pellèas he commented, “If that was music, I have never understood what music was.”

“Hommage national” to Gabriel Fauré at the Sorbonne, in the presence of President Alexandre Millerand, 1922.

Fauré’s comments did have a highly personal dimension, as he fundamentally disagreed with Debussy’s extra-marital arrangements. As such, he regarded Debussy and his musical influence as corrupt and wrote, “It’s a disastrous influence in the sense that it has diverted our French conception of music; it is one to be avoided.” It comes as no surprise that Debussy was equally critical of Fauré, calling him the “music-case of a band of snobs.” After a concert in 1903, Debussy writes, “We afterwards heard a Ballade for piano and orchestra by the master of charms, Gabriel Fauré, which was almost as lovely as Mme Hasselmans, the pianist.” A scholar writes, Fauré and Debussy shared more dislikes than likes: notably a horror of rhetoric, sentimentality, and the superficial and showy. Their common qualities were elegance, refinement, sensibility and a highly developed feeling for sonorous beauty.”

Gabriel Fauré: Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 2 in G minor Op. 117

Fauré relationship with Maurice Ravel was decidedly different, as Ravel was clearly his most talented student. At an early stage of the relationship, and after listening to the premiere of Histoires naturelles, Fauré commented, “I like Ravel very much, but I do not like the fact that he sets to music things like that.” Both were highly attracted towards songs and chamber music, and Ravel always admitted the profound influence of his teacher’s works. They disagreed in their attitude towards the orchestra, as it was the center of Ravel’s art, whereas Fauré considered “orchestration as something that could easily be used to conceal poverty of musical ideas.”

Gabriel Fauré playing the organ of the Église de la Madeleine, Paris (left) and the current exterior and interior of the church

Be that as it may, Ravel remained enthusiastic about Fauré’s music, and Fauré sought to praise the good points in a composer’s work rather than stress its faults in his musical criticisms. He wrote for Le Figaro between 1903 and 1921, and defined the critic’s role as follows. “I think that the chances of judging a work of art justly are much higher when one has oneself practiced and experimented in that art all one’s life. I think equally that a constant battle with the difficulties of that art inclines one very naturally towards leniency. The work of the critic obliges me to look beyond my own particular medium.”

Gabriel Fauré: L’horizon chimerique, Op. 118 (Jacques Herbillon, baritone; Theodore Paraskivesco, piano)

By 1920, Fauré had become a celebrity in his homeland. He was awarded the Grand-Croix of the Légion d’honneur, an honor rare for a musician. And on 20 June 1922 his friend Fernand Maillot organized a national tribute at the Sorbonne in the presence of President Millerand. A press report describes “a splendid celebration, in which the most illustrious French artists participated. It was a poignant spectacle indeed: that of a man present at a concert of his own works and able to hear not a single note. Fauré sat gazing before him pensively, and, in spite of everything, grateful and content.”

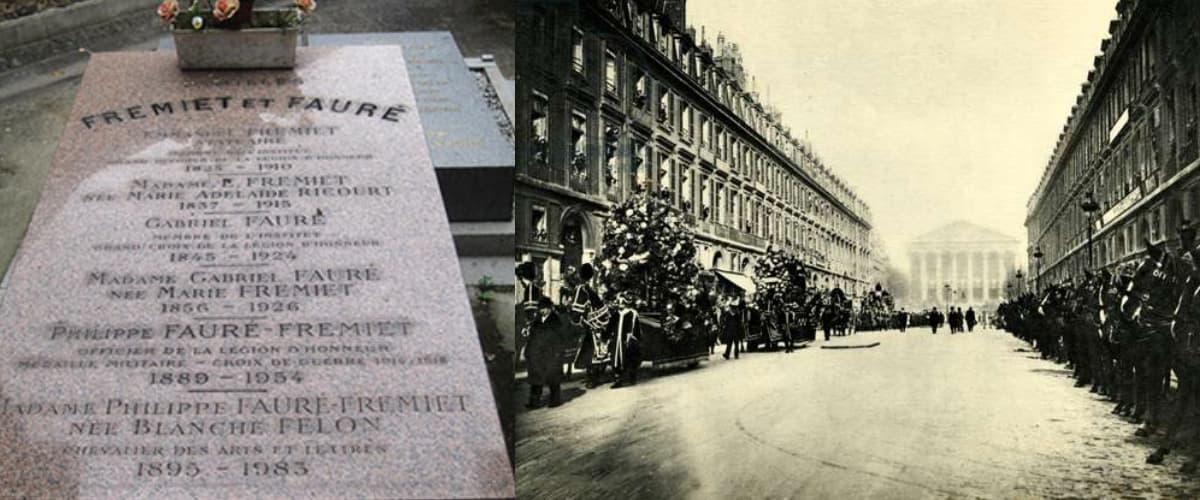

Fauré’s grave in Passy Cemetery, Paris (left) and his funeral in 1924 (right)

Fauré died from pneumonia on 4 November 1924 in Paris at the age of 79. His last words questioned, “Have my works received justice? Have they not been too much admire, or sometimes too severely criticized? What of my music will live? But then, that is of little importance.” The organization of a state funeral did initially not go smoothly. “A very important personage, when told of the death of Fauré asked unashamedly, “Who is he?” It took several days of heated discussions until the ministers were finally convinced. Fauré’s former place of employment, the Église de la Madeleine was chosen, and his own Requiem was performed. The Minister of Education and Fine Arts, M. Francois Albert gave the eulogy, and Fauré’s body was subsequently interred in the Passy Cemetery in Paris.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gabriel Fauré: Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 120