Edmund Leighton: Pelléas and Mélisande, 1910

(Williamson Art Gallery & Museum)

These days, when we hear of the doomed lovers Pelléas and Mélisande, we most often think of Claude Debussy’s opera, but there were other composers who took up the story by Maurice Maeterlinck.

In Maeterlinck’s 1893 play, Golaud finds Mélisande in the woods and marries her. After a while, however, she finds Golaud’s brother Pelléas to be of interest and after they are seen caressing in the woods, Golaud kills his brother and mortally wounds Mélisande, who later dies in childbirth, producing a very small baby girl.

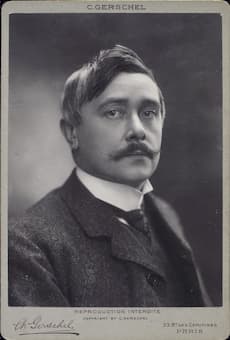

Maurice Maeterlinck, circa 1900

It’s a basic triangle love story that goes wrong, but Maeterlinck has given Mélisande a backstory that makes it all the more tragic. Mélisande is in the wood because she’s just escaped from a traumatising earlier marriage – she cannot remember her past. By the time she’s dying at the end, she doesn’t remember Pelléas either, nor does she seem to realize that she’s dying. She’s not the conniving wife that the basic story line could make her, mostly she just seems confused.

In the musical world, in addition to Debussy’s 1902 opera, a number of composers wrote incidental music for performances of the play, or symphonic poems on it. Let’s explore them.

Sarah Bernhardt as Pelléas, ca. 1905

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) wrote incidental music to a few plays. His music for Pelléas and Mélisande (1898) started as a piano work and then was orchestrated by Charles Koechlin. Despite the orchestration being done by another composer, Pelléas and Mélisande is considered one of Fauré’s finest orchestral works. The London production of Maeterlinck’s play was put on in London by the actress Mrs Patrick Campbell and was successful (unlike Maeterlinck’s original production, which quickly closed). The Campbell production was revived several times by Campbell, and translated into French, was also a success for Sarah Bernhardt….as Pelléas.

Gabriel Fauré: Pelléas and Mélisande, Op. 80 (arr. C. Koechlin) – I. Prelude – Andante molto moderato (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Heinz Holliger, cond.)

After the success of the play and its orchestration by his student Koechlin, Fauré returned to the music and created a Suite based on the 4 principal movements of the original version: Prélude, Fileuse, Sicilienne, and Molto Adagio (Mort de Mélisande).

Gabriel Fauré: Pelléas et Mélisande Suite, Op. 80 (Lorraine National Orchestra; Jacques Mercier, cond.)

Mélanie Bonis

Mélanie Bonis (1858-1937) attended the Paris Conservatoire at the behind of César Franck, but was removed by her parents, despite for the praise for her as a brilliant student, when she fell in love with another student. They married her off to an older man, with whom she had 3 children. Eventually, she resumed her compositional career, having a private life as Madame Domange and a music life as ‘Mel Bonis.’ Mélisande is one part of her larger Femmes de légende work, whose other movements are Phoebe, Desdémona, and Viviane. The works are very much Romantic character pieces, but also bring in elements of Impressionism in her use of whole-tone scales, dissonant chords, and arpeggiated textures.

Mélanie Bonis: Mélisande, Op. 34 (Veerle Peeters, piano)

In 1902-1903, Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) took Maeterlinck’s story as the inspiration for his polyphonic tone poem Pelléas and Mélisande. The composer wrote that its premiere was not entirely successful: ‘The first performance, 1905, in Vienna, under my own direction, provoked riots among the audience and even the critics. Reviews were unusually violent and one of the critics suggested putting me in an asylum and keeping music paper out of my reach….’ However, its next outing, in 1911 went well as did other performances in 1912 in Prague, Amsterdam, and St Petersburg. Schoenberg’s music consists of ‘intertwined counterpoint’ creating a dense texture that seems to capture the claustrophobic elements of the story.

Arnold Schoenberg: Pelléas und Mélisande, Op. 5 – Anfang – (Philharmonia Orchestra; Robert Craft, cond.)

Albert Edelfelt: Jean Sibelius, 1904

Sibelius’ 1905 incidental music for Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas und Mélisande was commissioned by the Swedish Theatre. Although Schoenberg’s tone poem had been released two months before Sibelius’ March 1905 premiere, there’s no evidence the Schoenberg had any influence on Sibelius’ work – it was far more indebted to the current fashion for Maeterlinck. When critics compared it to Debussy’s 1898 opera, they found that Sibelius had a different way to ‘clothe his own tone pictures in a subdued, gentle and restrained atmosphere’ than Debussy has with his ‘pianissimo mannerisms.’ The original incidental music had 10 parts and 9 of them found their way into the suite that Sibelius later arranged.

Jean Sibelius: Pelléas and Mélisande Suite, Op. 46 – VIII. The Death of Mélisande (Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra; Edward Gardner, cond.)

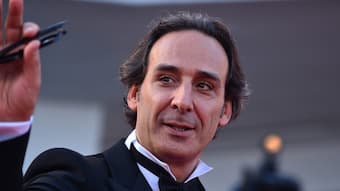

Alexandre Desplat

One of the latest composers to take up the tragic love story is film composer Alexandre Desplat. Known for his score to films such as Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Florence Foster Jenkins, and many others, he only recently turned to orchestral music. He chose to write a ‘symphonie concertante’ for flute rather than a flute concerto so that he could make the orchestral lines more important and not have the flute as the sole focus. He found writing for the concert hall freed him from the film constraints of time, dynamics, budget, deadlines, etc. but also placed him in an exposed position of having no guiding images, dialogue, or sound effects to help. The writing is very different from all the other Pelléas and Mélisandes that we’ve heard and is much informed by his film background.

Alexandre Desplat: Pelléas et Mélisande – III. Rosée de plomb, inexorables ténèbres (Emmanuel Pahud, flute; Orchestre National de France; Alexandre Desplat, cond.)

Despite being such an influential Symbolist play by Maurice Maeterlinck, and such an important opera by Claude Debussy, the story hasn’t really entered composers’ imaginations to a large degree. To have only 5 composer take up the tale in over a century seems like a missed opportunity. What would happen if you told this tale from the other side – not from all these men guiding a poor confused beauty, but from her side – a tale of constant trouble and fear? Ideas to consider for bringing this play into a new century, perhaps.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter