In 1865, Antonín Dvořák decided to write two full-scale symphonies, both nearly an hour in length. Composed within a couple of months, both works are imaginative and arresting, “yet clearly overlong.” At that time, Dvořák was basically unknown as a composer, as his musical activities focused on freelancing as a viola player in performances around Prague. It certainly was a bold undertaking for an inexperienced composer, and entirely out of line with the compositional mainstream in Europe, which focused on symphonic poems and highly programmatic symphonies.

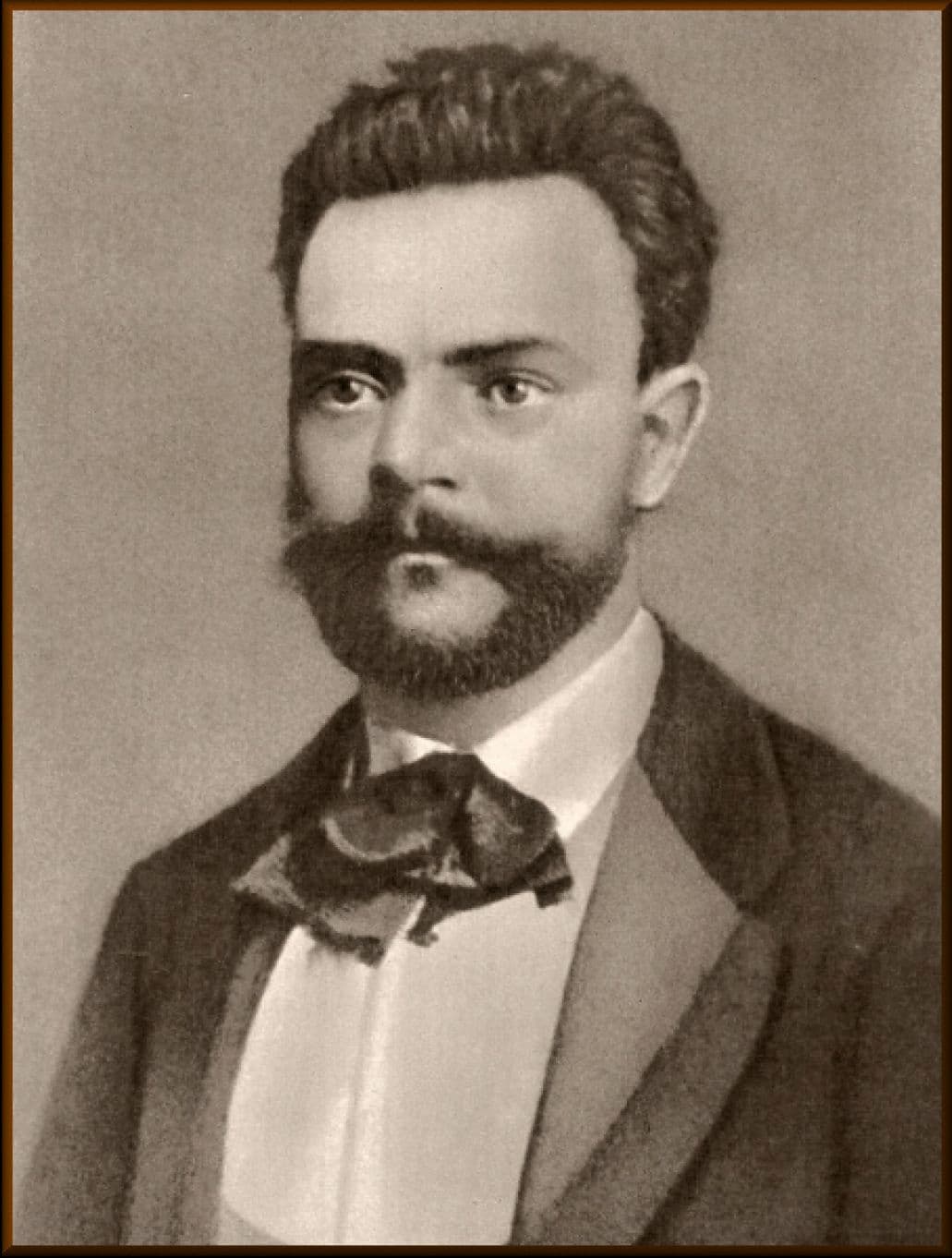

Dvořák in 1870

A scholar writes, Dvořák’s first and second symphonies “both benefit from the influence of Schumann, but there are unmistakable signs of originality. The “Scherzo” of the First is a slow polka and the Second, particularly in the revised version of 1887, has a melodic sweep that looks forward to Richard Strauss.” Dvořák’s symphonic experiments were not published during his lifetime, and the score to his 1st Symphony was found in a second-hand music shop in Leipzig, and first performed in 1936. His 2nd Symphony was performed only once, and after hearing it played in 1888, Dvořák made some revisions and shortened the work before storing it in a drawer.

Antonín Dvořák: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 10 “Allegro moderato” (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Antonín Dvořák

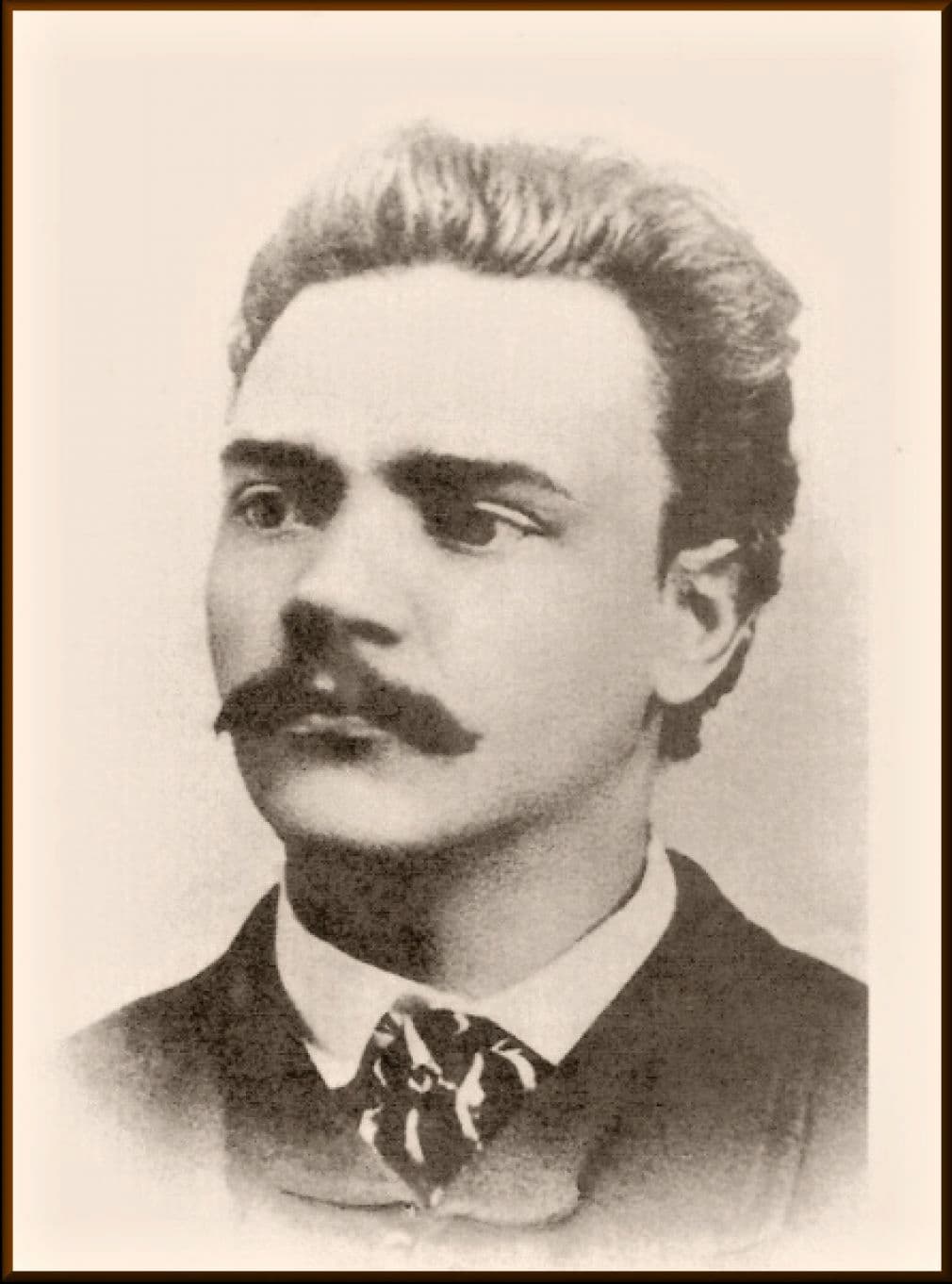

After completing his two symphonic experiments, Dvořák took a break of nine years before he returned to the symphonic medium. Between April and July 1873 he crafted his 3rd Symphony in E-Flat Major, a work that sees the composer finding his own distinctive compositional style. Although still strongly influenced by Richard Wagner in terms of instrumentation, and showcasing an unsettled approach to cyclical form, “the work does bear traits of the kind of original musical language Dvořák would use in the future, namely a variety of musical ideas, broad, arching melodies and an atmosphere of joyful optimism in the closing movement.” Written on the heels of Dvořák’s first successes as a composer, a biographer finds in this symphony “an expression of the same sense of patriotism and fervent interest in the future of the nation.” The work was premiered on 29 March 1874 in Prague with Bedřich Smetana conducting the “Filharmonie Orchestra.”

Bedřich Smetana, 1878

A contemporary critic writes, “the impression given by the composer’s latest work is close to breathtaking; then again, it is such that the listener’s attention and perception start to grow weary. The composer has a wealth of ideas at his disposal, and he always offers them to us, his hands full, like some kind of Croesus. There is something remarkable about this; his creative fantasy presents itself here in the most wonderful splendour. Nevertheless, it is also apparent that the composer is as yet unable to control the high-spirited steed of his imagination; he still allows himself always to be carried by his enthusiasm alone, with the result that the structural proportions of the work become less organic, and lose their symmetry and clarity.”

Antonín Dvořák: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 10 “Adagio molto” (London Symphony Orchestra; István Kertész, cond.)

Dvořák’s 3rd Symphony is primarily lyrical; a fact alluded to by Johannes Brahms. He was particularly enthusiastic about the beautiful melodies, and wrote, “it is pure love, and it does one’s heart good!” The opening movement sounds a sense of exalted pathos conveyed by the majestic and broadly arching principle theme. The second movement is contemplative in nature, and the Finale provides a joyful atmosphere that incorporates characteristics of a scherzo movement. The fact that this symphony does not sound like a proper “Scherzo” was described as basic inexperience. A critic suggested that the three movements could be three symphonic poems but that the absence of a scherzo prevented the work from truly being a symphony. And a contemporary reviewer wrote, “The poetic conception is interesting indeed, the basic motifs are for the most part full of feisty emotion and expression, the thematic treatment is thorough and rich in the extreme, and the orchestration attains the level of modern art… God willing, this young composer will attain greater serenity and will be more temperate in his deliberation in his subsequent symphonic works, and will thus achieve perfection in his musical creations.”

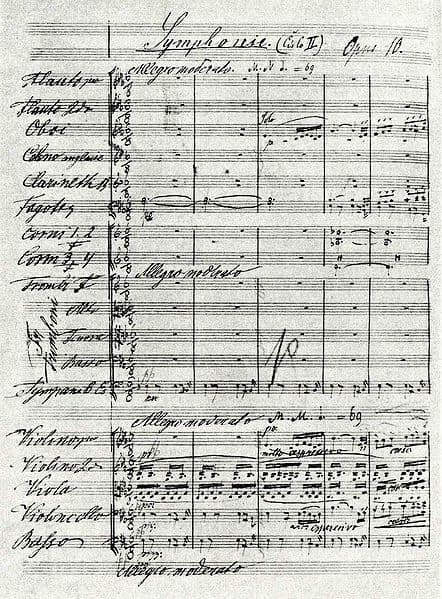

Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony No. 3

The composer subsequently submitted the score, together with his fourth symphony and other works with his application for a state scholarship in 1874, which was ultimately granted. Dvořák held particular affections for this symphony, as he frequently returned to it and apparently “fondly looked through the score only a few days before his death.” However, the publication of the score had to wait until 1912.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonín Dvořák: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 10 “Finale: Allegro vivace” (Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Jiří Bělohlávek, cond.)