Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) was already considered the greatest living composer when the impresario Johann Peter Salomon invited him to compose and conduct first six, and later six more symphonies for the cosmopolitan audiences in London. The British press hailed him as “the greatest composer in the world,” and according to scholars, “Everything Haydn learned in forty years of experience went into these symphonies. While he did not depart radically from his previous work, he brought all the elements together on a grander scale, with more brilliant orchestration, more daring harmonic conceptions, more intense rhythmic drive, and especially, more memorable thematic inventions.”

Portrait of Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1791

His first journey in 1791-1792 became an overwhelming success, and Haydn was invited back in 1794-1795. Haydn already had carefully analyzed the tastes of his London audiences, and he certainly knew how to make a grand entrance. When he sat down at the fortepiano on 2 March 1795, as part of a concert series called the “Opera Concerts” at the King’s Theatre, the orchestra greeted the audience with a long roll on the timpani. “The introduction excited deepest attention,” wrote the Morning Chronicle, and it is pretty obvious where the nickname “Drumroll” comes from.

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 103 in E-flat Major, “Drumroll” – I. Adagio – Allegro con spirito – Adagio – Tempo I (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

The Composition

Portrait of Johann Peter Salomon by Thomas Hardy

For Haydn, the timpani roll and its treatment later on in the work was not a cheap attention getter, but “the first of many imaginative features in this second to last of Haydn’s symphonies.” In fact, it leads into a slow introduction that presents a mysterious melody in unison low strings, and bassoon. It is almost impossible to get a clear reading of the meter, and it seems to quote the famous funeral chant “Dies Irae.” With the strings spinning an eerie chromaticism, this section has been described as “the most mysterious, portentous symphonic opening before Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ and Beethoven’s Ninth.” When the music breaks into a rustic melody in the oboe and violin over a waltz-like accompaniment, it comes as a complete surprise. Given the ominous opening, and the continuous presence of Dies Irae fragments, it sounds almost naïve. This quality is reinforced by the secondary subject, which also makes reference to a dance genre. Near the end of the movement, and after a series of apocalyptic crashes and a dramatic pause, the introduction and the drumroll return. This time, however, the specter of doom is banished once and for all in a lively dance transformation that reinforces the link between the introduction and the Allegro proper.

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 103 in E-flat Major, “Drumroll” – II. Andante più tosto allegretto (Munich Philharmonic Orchestra; Sergiu Celibidache, cond.)

The second movement “Andante” presents a theme and variations, possibly based on a Croatian folksong, that vacillates between the tonalities of C minor and C major. It’s not really a set of variations on two themes, but the movement relies on Haydn’s ingenious transformation of the opening theme. The violin solo was specially written for Giovanni Battista Viotti, who co-directed the orchestra from his position of concertmaster. An extended minuet and trio with long development sections leads to a simple horn call that opens the finale. “Designed as a true symphonic apotheosis, this highly imitative movement sustains fugal treatment throughout.” It has been noted that this finale is one of the longest in the London Symphonies. “It is one of the great tours-de-force, formally speaking, of Haydn’s career: the creation of a long movement on a single theme in which our interest never flags; on the contrary, it is a Finale of unusual tension and strength.” To be sure, Haydn created a movement of thrilling harmonic and contrapuntal drama that may or may not be based on a “snatch of Croatian folksong.” The “Drumroll Symphony” has, rather unusually for Haydn, an alternate ending. Haydn removed 13 measures towards the end to possibly “not hold up the course of the movement.”

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 103 in E-flat Major, “Drumroll” – III. Menuet – Trio (South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden; Michael Gielen, cond.)

Critics’ Reception

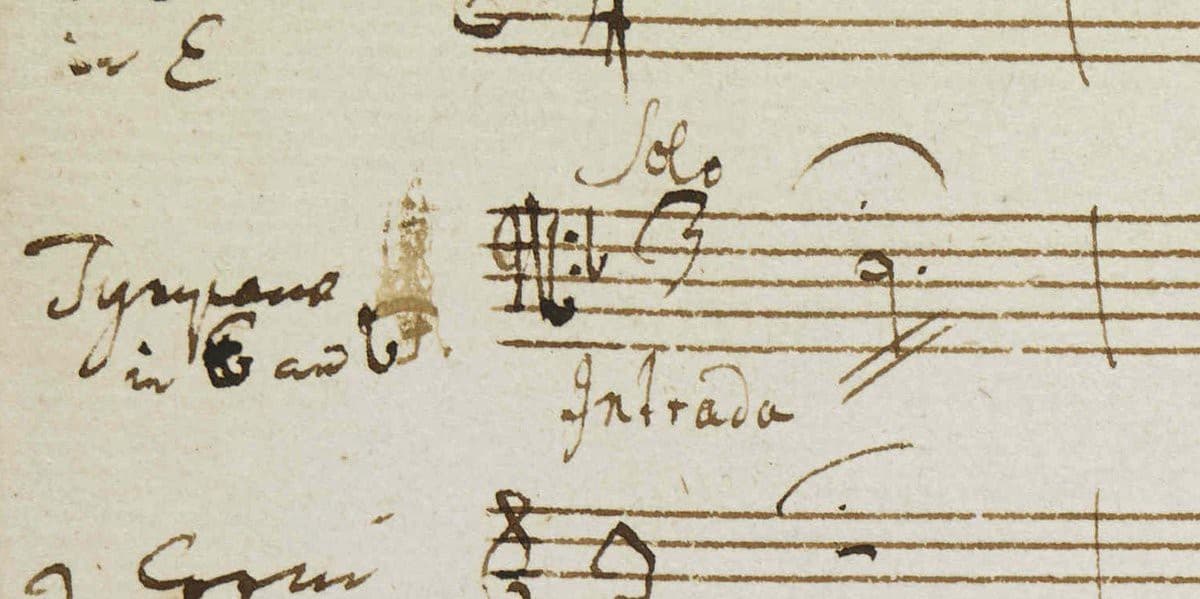

Timpani’s cadenza in Haydn’s “Drumroll Symphony”

We know that the orchestra Haydn used was unusually large for the time, consisting of about 60 players. The premiere was a huge success, and The Morning Chronicle writes. “Another new Overture [i.e., symphony], by the fertile and enchanting Haydn, was performed; which, as usual, had continual strokes of genius, both in air and harmony. The Introduction excited deepest attention, the Allegro charmed, the Andante was encored, the Minuets, especially the trio, were playful and sweet, and the last movement was equal, if not superior to the preceding.” These sentiments were echoed by The Sun reporting “Haydn’s new Overture was much applauded. It is a fine mixture of grandeur and fancy…the second movement was encored.” Haydn did complain that British audiences were “inattentive and had a tendency to be noisy,” yet he absolutely loved his time in London. It was Mozart who said that Haydn could “amuse and shock, arouse laughter and deep emotion as no-one else,” and that I would argue, is fantastically demonstrated in his “Drumroll Symphony.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 103 in E-flat Major, “Drumroll” – IV. Finale: Allegro con spirito (English Chamber Orchestra; Jeffrey Tate, cond.)