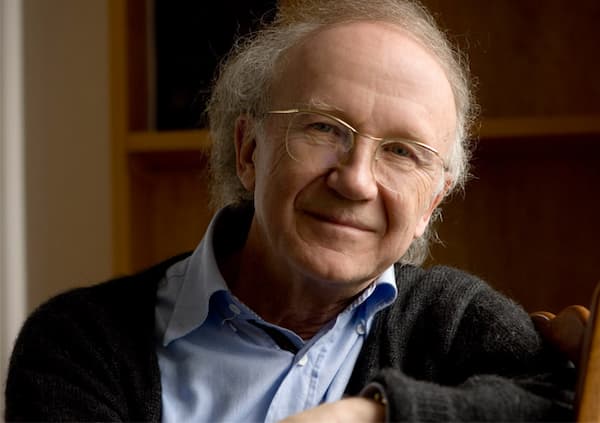

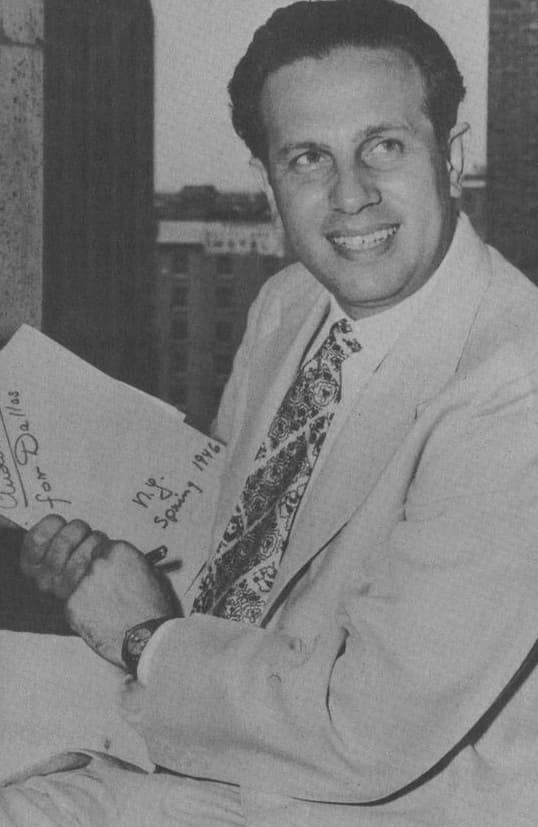

Heinz Holliger, born on 21 May 1939, achieved worldwide fame as an oboist, performing and recording some of the earworm pieces from the Baroque and Classical periods. Yet, as he explained on the occasion of his 80th birthday, “composing has always been much more important to me than playing.” Holliger is also a sought-after conductor, but he describes himself simply as “a musician. And that includes everything I do.”

Heinz Holliger

In his compositions and elsewhere, Holliger has always been a fierce advocate of contemporary music, and given his accomplishments and musicianship, it is only natural that a good many composers have written works specifically for Heinz Holliger.

But what is more, Heinz Holliger was married to Ursula Holliger, an exceptional harpist known for her commitment to contemporary music. Alone and together, they created a multitude of works, and we thought it might be fun to explore some of these dedicated compositions.

Isang Yun: Oboe Concerto

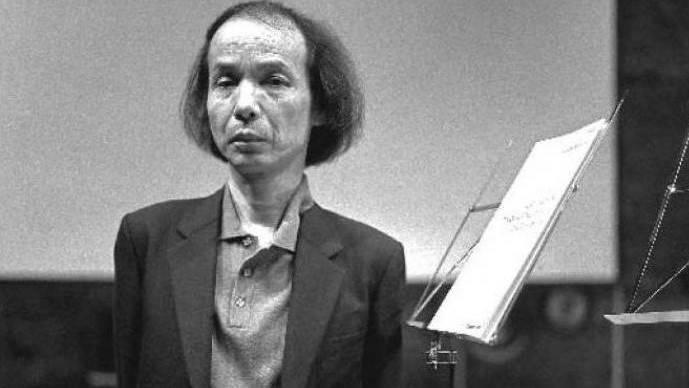

Ursula Holliger

Isang Yun: Oboe Concerto (Heinz Holliger, oboe; Bremen Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie; Heinz Holliger, cond.)

In his music, Isang Yun, born on 17 September 1917, explored aesthetic and philosophical issues relating to Asian traditional music, Chinese Taoism and Western avant-garde compositional procedures. “I was born in Korea and projected that culture,” he said, “but I developed musically in Europe. I don’t need to organise or separate elements of the cultures. I am a unity, a simple person. It’s a synthesis.”

Dedicated to his good friend Heinz Holliger, the Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra dates from 1990. It was a late work, free of imitations and stylistic allusions, and the lyrical subject sounded in the solo oboe is striking. In a sense, the soloist stands for the individual, and the orchestra is a representation of the world. The soloist stands at the beginning, but there are helpers like the violin or the cello.

Yun presents isolated monologues accompanied by metallic wind and percussion instruments, lending them a militaristic flavour. This might not be surprising as the work was composed in Pyongyang, the capital city of North Korea. However, it premiered with the Beethoven Hall Orchestra of Bonn in Berlin, with Heinz Holliger as the soloist. It is dedicated to “Heinz Holliger” and “In Memory of Serge and Natalie Koussevitzky.”

Elliott Carter: Trilogy

Ursula and Heinz Holliger

Elliott Carter: Trilogy (Heinz Holliger, oboe; Ursula Holliger, harp)

Elliott Carter (1908-2012) explained that he composed the Trilogy for oboe and harp for “those great performers and dear friends, Ursula and Heinz Holliger.” The work is based on the last two stanzas of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Sonette an Orpheus.

But existence is still enchanting for us;

in hundreds of places it is still pristine,

A play of pure forces, which no one can touch

without kneeling and adoring.

Words still peter out into what cannot be expressed…

And music, ever new, builds out of the most tremulous stones

her divinely consecrated house in unexploitable space.

Each of the three sections of Trilogy was written for a special occasion. “Bariolage” is a harp solo written for a festival of Carter’s music given in Geneva in March 1992, for Ursula Holliger, to whom it is dedicated. “Inner Song” was written for a festival in Germany, and it was performed and is dedicated to Heinz Holliger. “Immer Neu” is dedicated to both Ursula and Heinz Holliger, and it provides a duet for them.

Ernst Krenek: 4 Pieces

Ernst Krenek: 4 Pieces, Op. 193 (Fabian Menzel, oboe; Bernhard Endres, piano)

Ernst Krenek (1900-1991) frequently changed composition directions throughout his long creative career. By the late 1920s, Krenek turned away from the neo romantic style and turned to Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique. Although he took a different attitude towards dodecaphonic music than Schoenberg, he greatly believed in its uncompromising standards and possibilities for further development. In one way or another, the twelve-tone system coloured his work for the remainder of his career.

Krenek also experimented with free atonality, jazz-oriented compositions and eventually a return to contextual tonality. However, Krenek always retained his own sound through all his musical style changes, as “he demonstrated his independence from any tonal system that might be imposed upon him.” In the event, he was one of the most fascinating composers of the 20th century.

The Four Pieces, Op. 193, written for Heinz Holliger, are serial works, but that is not really noticeable. He always divided tone rows and varied permutations to suit his creative freedom. Completed in Tujunga, California, on 31 March 1966, the Four Pieces are seriously experimental, making use of Holliger’s technical skill of tone production. There are plenty of glissandi, flutter-tonguing and multiphonics that bring expressivity to the piece.

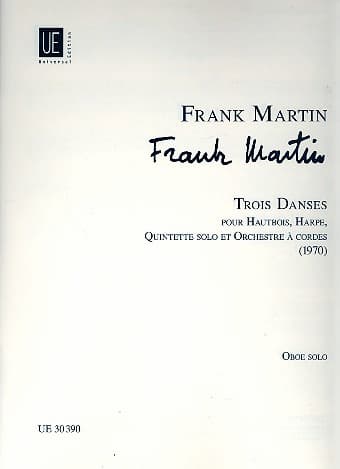

Frank Martin: Three Dances

Frank Martin: 3 Dances

Frank Martin: Three Dances (Hansjörg Schellenberger, oboe; Margit-Anna Süss, harp; Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra; Zoltán Peskó, cond.)

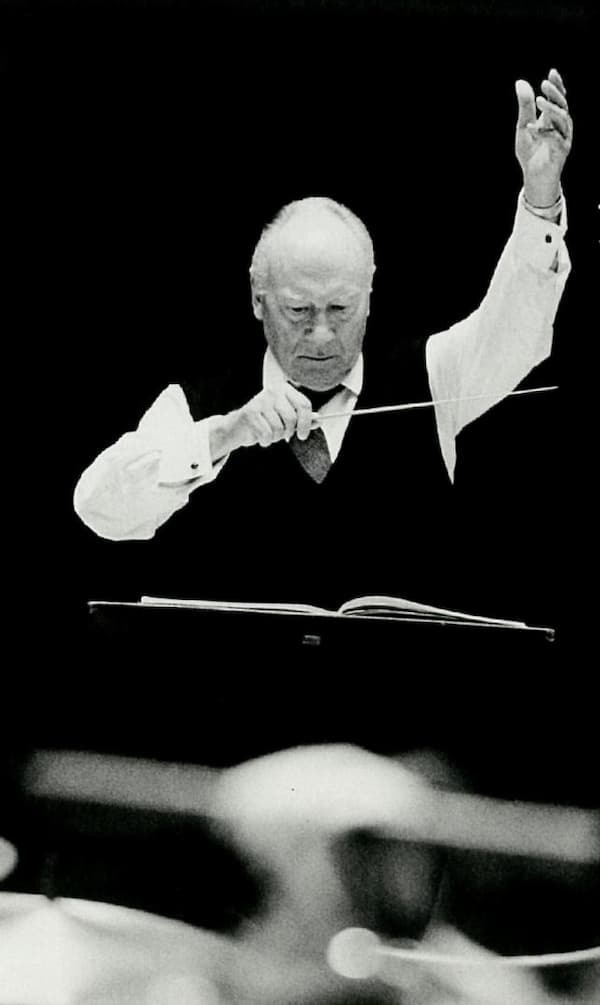

A huge number of commissions for Ursula and Heinz Holliger originated with Paul Sacher, the legendary conductor, patron, and impresario. An artist of unusual stature and one of the world’s richest men, he became one of the most influential figures in 20th-century music by commissioning and performing contemporary music. Sacher was primarily concerned to make contemporary works accessible and understandable for his audience. Some of the composers engaged included Hindemith, Bartók, Stravinsky, Strauss, and Frank Martin.

In 1970, Frank Martin (1890-1974) was commissioned by Paul Sacher to compose a work for Ursula and Heinz Holliger. Martin responded with his Trois Danses, a work that started with the composer’s “profound interest in certainly rhythmic peculiarities of the flamenco.” As the composer explained, “In Andalusia, the originally purely vocal flamenco developed into a style of dance and music strongly influenced by elements of gypsy music.”

Martin described the basic character of the dances as fantasies, and the most characteristic of these dances is heard in the opening “Seguiriya.” It features a traditional rhythmic formula, while the second dance bears the name “Soledad.” Meaning solitude, it is a free and very personal interpretation of the flamenco style. The third dance, “Rumba”, is based on a well-known rhythm, “which I have blended in my own manner with even bars of four quarter notes.”

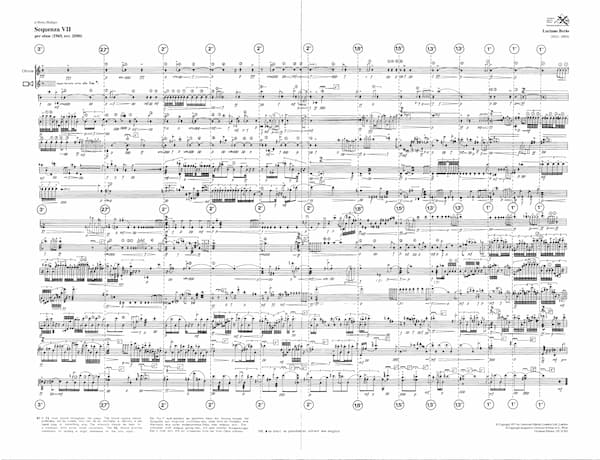

Luciano Berio: Sequenza VII

Luciano Berio: Sequenza VII

Luciano Berio: Sequenza VII (Celine Moinet, oboe)

Luciano Berio (1925-2003) was Italy’s most important contemporary composer. Already in the 1950s, he started questioning the rigid avant-garde with his experimental views. He began to pursue a substantial number of different approaches, from electronic music and indeterminacy to experiments using spoken texts as the basic material for composition.

The most important cycle in Berio’s chamber music is nine works called “Sequenza.” The term comes from Gregorian chant, but Berio explained that it has no relation to medieval church music but comes from the fact that these pieces are based mainly on sequences of a harmonic character and various types of instrumental actions. All nine works are for a solo instrument or solo vocals without accompaniment.

Composed for Heinz Holliger in 1969, Sequenza VII discovers new sound spaces and colours for the instrument without relying on serial music. Berio explained, “serial procedures cannot guarantee anything in themselves, and no idea is so miserable that it cannot ultimately be serialised. Sequenza VII pivots around the pitch “B natural,” and presents multiple fragments that traverse the entire range of the oboe in order to investigate unaccustomed sonic constructions and playing modes.

Witold Lutosławski: Double Concerto for Oboe and Harp

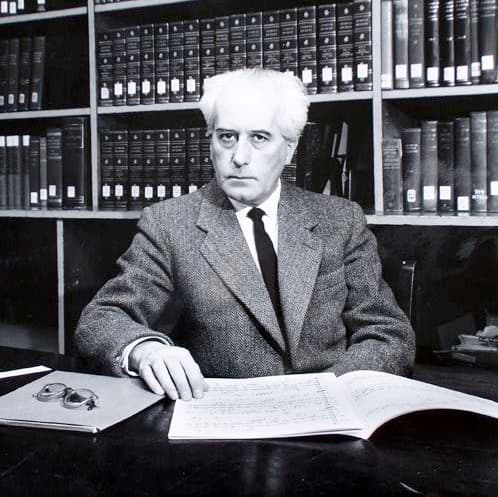

Paul Sacher

Witold Lutosławski: Double Concerto for Oboe and Harp (Heinz Holliger, oboe; Ursula Holliger, harp; Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Witold Lutosławski, cond.)

The Polish composer and conductor Witold Lutosławski (1913-1994) is counted among the major composers of 20th-century classical music. In fact, scholars generally regard him as the most significant Polish composer since Szymanowski, and possibly the greatest Polish composer since Chopin. Lutosławski composed in most traditional genres, including

symphonies, concertos, orchestral song cycles, other orchestral works, and chamber works.

Ten years after Frank Martin’s Trois Danses, Paul Sacher again commissioned and conducted the world premiere of a work featuring Heinz and Ursula Holliger. The Lutosławski Double Concerto for oboe, harp and chamber orchestra, from its very inception, “envisioned the particular performance techniques of the two soloists.” The key idea behind the piece, according to the composer, “was to avoid a melodic theme, and rather focus on the form, the order, and certain procedures.”

Lutosławski explained, “I wanted to write an aleatoric piece for polyphonic and monophonic instruments. In this work, chance plays a larger role than in the past. Although it may sound paradoxical, the piece appears organised to a very high degree; yet the different interpretations can vary to a considerable extent.” The opening movement sounds a series of marches, ending with a funeral march. The experimental second movement consists of short episodes, and only the beginning and the end are precisely noted. In the middle, the soloists can choose the duration of their performance at will, in a procedure that the composer once described as “sculpturing of liquid matter.”

Antal Doráti: Duo concertante for Oboe and Piano

Antal Doráti

Antal Doráti: Duo concertante for Oboe and Piano (Alexei Ogrintchouk, oboe; Leonid Ogrintchouk, piano)

Hungarian-born Antal Doráti (1906-1968) was a fantastic orchestral technician, whose clear and disciplined conducting made him an exceptional builder of orchestras. Orchestra musicians found him rather demanding, but the results were generally impressive. He started as a conductor of the successor company to Diaghilev’s ballet company, the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, and later became chief conductor of the American Ballet Theatre and the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra.

While his distinguished conducting career is well-documented, we know relatively little about Doráti the composer. As he once wrote, “I cannot permit myself to pass over the fact that writing music is the very focal point of my life, and that I regard myself not as a composing conductor but the contrary: a conducting composer.” Doráti was a composition student of Bartók, Kodály and Weiner, and his music is born out of his Hungarian roots but is also contemporary and forward-looking.

Doráti was fascinated with the playing and artistry of Heinz Holliger, not only in terms of virtuosity but also by his extraordinary range of expression, dynamic, and colour of sound as well as his creative mind. As such, he composed a number of works, including the Duo Concertante from 1983, written for Holliger and the Hungarian pianist András Schiff. Doráti created a Hungarian Rhapsody for an instrument that is not associated with traditional Hungarian music. The slow and free lassú is followed by a virtuosic friss or gypsy dance.

Tōru Takemitsu: Eucalypts I

Tōru Takemitsu

Tōru Takemitsu: Eucalypts I (Heinz Holliger, oboe; Aurèle Nicolet, flute; Ursula Holliger, harp; Basel Ensemble; Jürg Wyttenbach, cond.)

The largely self-taught Japanese composer Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996) developed a distinct musical language by writing modal melodies emerging from a chromatic background and the suspension of regular meter. As a composer, Takemitsu positioned himself between two traditions. As he once remarked, “I would like to develop into two directions at once, as a Japanese in tradition and as a Westerner in innovation.” His music exudes an ethereal sense of space and detachment, yet he simultaneously and pointedly explores the space between objects, “an area full of energy.”

For the Zurich “Collegium Musicum”, Takemitsu composed Eucalypts I, which included solo parts for the flautist Auréle Nicolet, and for Heinz and Ursula Holliger. Scored for three soloists and string orchestra, Takemitsu later arranged the work for three solo parts alone. Layers of solo instrumental lines are superimposed upon one another to create a densely polyphonic, richly dissonant texture.

However, the superficially atonal impression created by this global texture is “belied by a closer inspection of the harmonic details from which it is built up, many of which turn out to be of modal derivation.” There is a remarkable lack of thematic connection between the soloists and the ensemble materials. Let’s not forget that Takemitsu is writing for three prestigious soloists, “where the new virtuosity is exploited to the full in a multitude of extended instrumental techniques.”

Sándor Veress: Sonatina for Oboe, Clarinet and Bassoon

Sándor Veress

Sándor Veress: Sonatina for Oboe, Clarinet and Bassoon (Heinz Holliger, oboe; Elmar Schmid, clarinet; Klaus Thunemann, bassoon)

Sándor Veress (1907-1992), a Swiss composer of Hungarian origin, was educated at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest. He studied composition with Zoltán Kodály, and piano with Béla Bartók. As an assistant of László Lajtha, he did field research on Hungarian, Transylvanian, and Moldavian folk music. Veress counted György Ligeti, György Kurtág, and Heinz Holliger, among his most famous composition students.

As a composer, Veress loved the combination of melodic phrases from Hungarian folk songs in a contrapuntal manner. Looking towards Italian vocal polyphony, he freely handled intervals independent of tonality. He did compose in a twelve tone medium, however, it is almost always oriented to a tonal centre, or central tone. And it is always fun, as you can hear in the Sonatina for Oboe, Clarinet, and Bassoon.

Krzysztof Penderecki: Capriccio for Oboe and 11 Stings

Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020) probably needs little introduction, as in 2012, he was called “arguably Poland’s greatest living composer.” A winner of many prestigious awards, his Capriccio for oboe and eleven strings was written for and premiered by Heinz Holliger in Lucerne on 26 August 1965.

In this work, scholars and critics hear a lighter side of Penderecki’s thinking, as the initial gesture centres on a single note obsessively repeated by oboe and strings. The composer exposes a wide range of playing techniques leading to a piquant oboe cadenza. With the strings re-joining, it all sounds a bit confrontational, but there is underlying humour, and all tension vanishes into thin air.

This short blog can only scratch the surface of the incredible riches inspired by Heinz and Ursula Holliger. Apologies to a whole host of composers not featured, but I hope this little overview can provide a sense of the vast variety of contemporary music composed in the second half of the 20th century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter