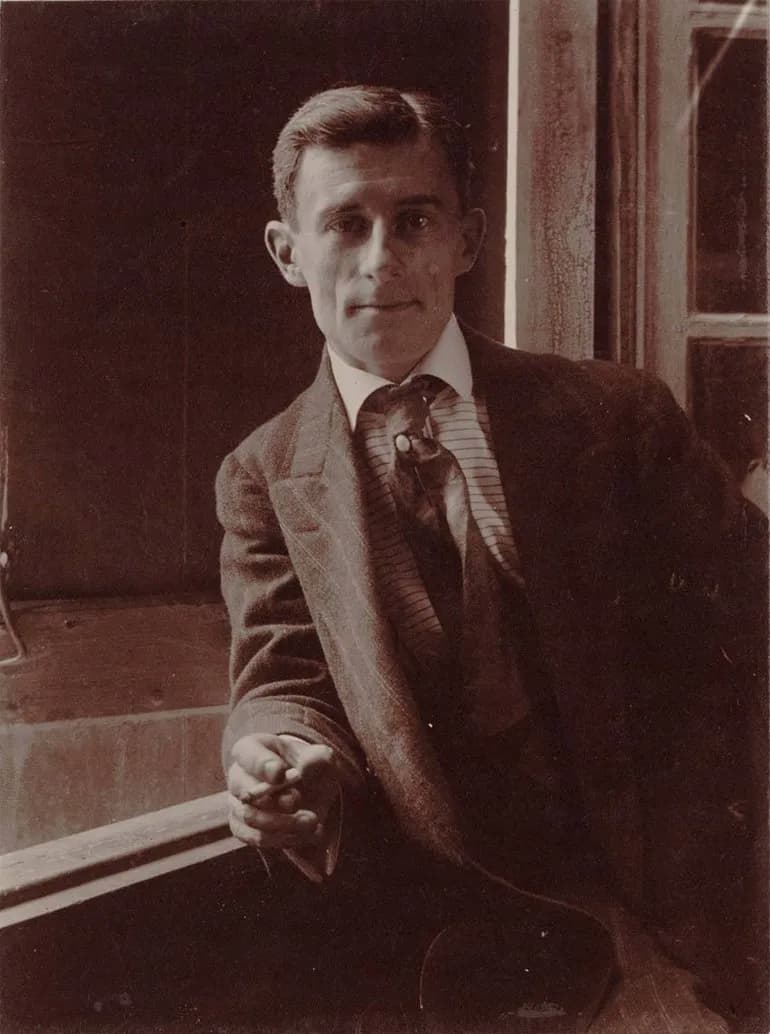

Nicolas Slonimsky

Nicolas Slonimsky (1894-1995) was a child prodigy, pianist, composer, conductor, scholar, lexicographer, and world traveler. His legacy continues to influence many musicians through his writings and compositions. Best known as the editor of Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Music, and author of the Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, Lexicon of Musical Invective, and Music Since 1900. While many people might have read his articles, his life and his music compositions are largely ignored. However, his humor, irony, and creativity can be found in both his writings and compositions. Indeed, he embraced music throughout his long life, and he composed nearly a hundred works, including some orchestral works, several vocal works, and many piano pieces.

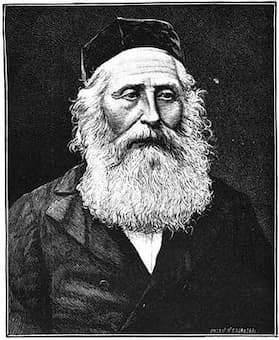

Zinovii Slonimsky, grandfather of Nicolas Slonimsky

Nicolas Slonimsky was born into an educated family, well regarded in the Russian science and arts world. His grandfather, Zinovii Slonimsky (known as Chaim Selig Slonimsky), was a famous scientist and publisher who invented the first telegraph. His father, Ludwig Slonimsky (1849-1918), was a journalist who wrote the first critical essay about Marx’s Communist Manifesto ever published in Russia. Nicolas Slonimsky’s musical inspiration perhaps came from his aunt, Isabelle Vengerova, a renowned pianist, and music teacher. She helped found the famous Curtis Institute, and she taught many famous students there, including Leonard Bernstein, Gary Graffman, and Samuel Barber. She was Nicolas Slonimsky’s first piano teacher.

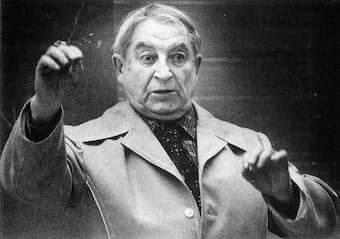

Sergei Slonimsky, nephew of Nicolas Slonimsky

His nephew, Sergei Slonimsky (1932-2020), was also a composer, pianist, and musicologist. His compositions display a variety of genres, including symphonies, operas, and concertos. He also wrote piano works for four hands and six hands, such as Tale of the Cat in Jackboots.

Sergei Slonimsky: Tale of the Cat In Jackboots

(With permission by Electra Slonimsky Yourke)

Nicolas Slonimsky lived the majority of his life in the United States. Before moving to the States he gained reputation as a pianist for the famous conductor Serge Koussevitzky and operatic tenor Vladimir Rosing. In 1923, Slonimsky moved to the United States where he studied composition and conducting. He also took the position of opera coach at the Eastman School of Music in New York. In 1925, he moved to Boston to serve as an assistant to Koussevitzky at the Boston Symphony Orchestra. That same year, he composed a set of five Advertising Songs. The texts were full of humor and satire. Perhaps for that reason, these songs were not used in the actual advertisement, and they were not published until the 1980s. Children Cry for Castoria was Slominsky’s favorite song of the set, here is a performance of the aged composer singing it.

Nicolas Slonimsky: Children Cry for Castoria

In 1926, he founded the Boston Chamber Orchestra and performed Music written by contemporary and experimental composers, such as Henry Cowell and Charles Ives. His interest in experimental works is demonstrated in his compositions. In the summer of 1928, he wrote Studies in Black and White for piano. Slonimsky mentioned this work was “too anti-pianistic” and “did not sell” at the time. Indeed, this multi-movement work consists of many experimental elements, such as the dissonant effect created by playing the right hand on white keys and the left hand on black keys, with complex rhythmic patterns in each hand. However, the experimental work is enjoyable to play and perhaps more acceptable to our modern ears.

In 1926, he founded the Boston Chamber Orchestra and performed Music written by contemporary and experimental composers, such as Henry Cowell and Charles Ives. His interest in experimental works is demonstrated in his compositions. In the summer of 1928, he wrote Studies in Black and White for piano. Slonimsky mentioned this work was “too anti-pianistic” and “did not sell” at the time. Indeed, this multi-movement work consists of many experimental elements, such as the dissonant effect created by playing the right hand on white keys and the left hand on black keys, with complex rhythmic patterns in each hand. However, the experimental work is enjoyable to play and perhaps more acceptable to our modern ears.

Nicolas Slonimsky: Studies in Black and White (Nicolas Slonimsky, piano)

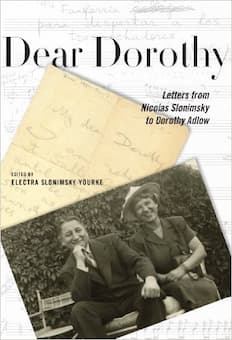

Cover of Dear Dorothy- Letters from Nicolas Slonimsky to Dorothy Adlow (Edited by Electra Slonimsky Yourke)

In Boston, he met his wife, Dorothy Adlow, and they married in 1931. Adlow was an art critic. They had one daughter, Electra, who was born in 1933.

In 1941, he took on a trip to Latin America. He collected vast materials, which can be seen in his book Music of Latin America. In the book, Slonimsky provides a comprehensive overview of musical styles and background of twenty countries in Latin America, as well as his personal feelings and experience of the trip.

Nicolas Slonimsky with his family (With permission by Electra Slonimsky Yourke)

While Slonimsky aimed to collect materials for writing his book, he was also inspired to write few compositions based on folklore styles in Latin America. Modinha Russo-Brasileira was adapted from a melody he heard during the trip. There was a dispute over the origin of the tunes; some claimed it was Russian, others claimed it was Brazilian. Nicolas Slonimsky chose a compromise with this title. He made two versions of this composition; one is a piano version, and the other is a wordless “vocalize” version. Laurindo Almeida, a famous Brazilian guitarist, later transcribed the piece for two guitars.

Nicolas Slonimsky: Modinha Russo-Brasileira (arr. L. Almeida for 2 guitars) (Laurindo Almeida, guitar)

Slonimsky also wrote a set of variations based on a Brazilian tune under the title My Toy Balloon for orchestra which includes 100 colored balloons popped at the climax. This work contains the theme and six variations. The theme is based on a folk tune presented by a brass chorus. Each variation has its own title. One variation, titled With Apologies to Brahms, is based on Brahms’ famous lullaby. Overall, it is a piece of very playful music for both listeners and performers. In additional to the orchestral version, Slonimsky also wrote a piano version for this work.

Nicolas Slonimsky: Variations on a Brazilian

![]() His book Music of Latin America was published in 1945. In the following decade Slonimsky wrote a number of books that remain popular and influential today. Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (1947) has impacted many musicians, and you can even find new videos talking about the application of this book on YouTube today. Lexicon of Musical Invective (“Critical Assaults on Composers since Beethoven’s Time”), published in 1948, is another popular work by Slonimsky. Peter Schickele describes it as “a supermarket tabloid of classical music” in the foreword of the book. The book is a collection of hilarious critiques of many influential composers. In 1958, Slonimsky was appointed as the editor of Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, providing invaluable insights and biographies of artists in all musical genres.

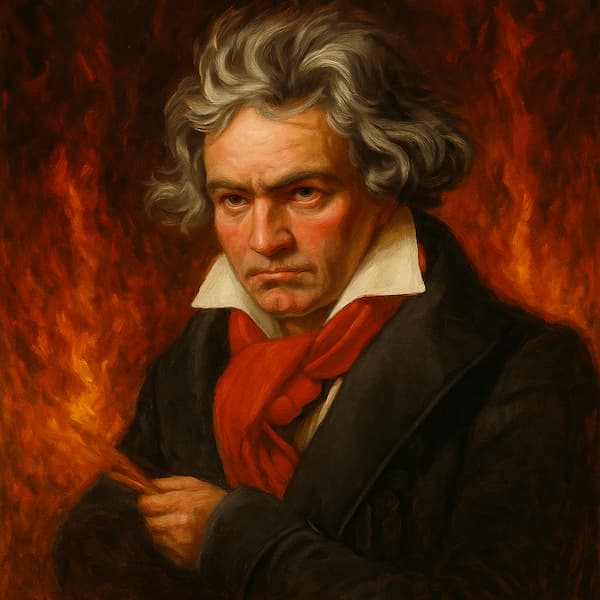

His book Music of Latin America was published in 1945. In the following decade Slonimsky wrote a number of books that remain popular and influential today. Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (1947) has impacted many musicians, and you can even find new videos talking about the application of this book on YouTube today. Lexicon of Musical Invective (“Critical Assaults on Composers since Beethoven’s Time”), published in 1948, is another popular work by Slonimsky. Peter Schickele describes it as “a supermarket tabloid of classical music” in the foreword of the book. The book is a collection of hilarious critiques of many influential composers. In 1958, Slonimsky was appointed as the editor of Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, providing invaluable insights and biographies of artists in all musical genres.

Nicolas Slonimsky with John Cage (With permission by Electra Slonimsky Yourke)

Slonimsky moved to Los Angles after his wife’s passing in 1964. In Los Angles, he taught briefly at UCLA. He remained very active even late in his life. His autobiography was published when he was 94, and he was filmed in a documentary on his 98th birthday. He passed away at the age of 101. His publications remain significant to many music lovers and scholars. His daughter, Electra, continues his legacy after his death. She has collected and organized his writings and published a series of books. I would like to end by acknowledging Electra’s help with this article. I am honored to have had some email correspondence with her during the writing process. I am also heartened to know that she continues to bring his work to a wider audience.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter