Paying tribute to unexpected sources of inspiration

In my childhood years as a musician, I was inspired – paradoxically (I say as a concert pianist) – by people who, though they had little musical knowledge or training, were highly enthusiastic about non-classical musical genres.

Nowadays, “crossover” as a musical genre in itself is all the rage: we are encouraged to blur the boundaries between art and non-art music – or rather to find the art in everything. But my parents and grandparents grew up within a strict “never-the-twain-shall-meet” mentality – and it was one they would largely eschew.

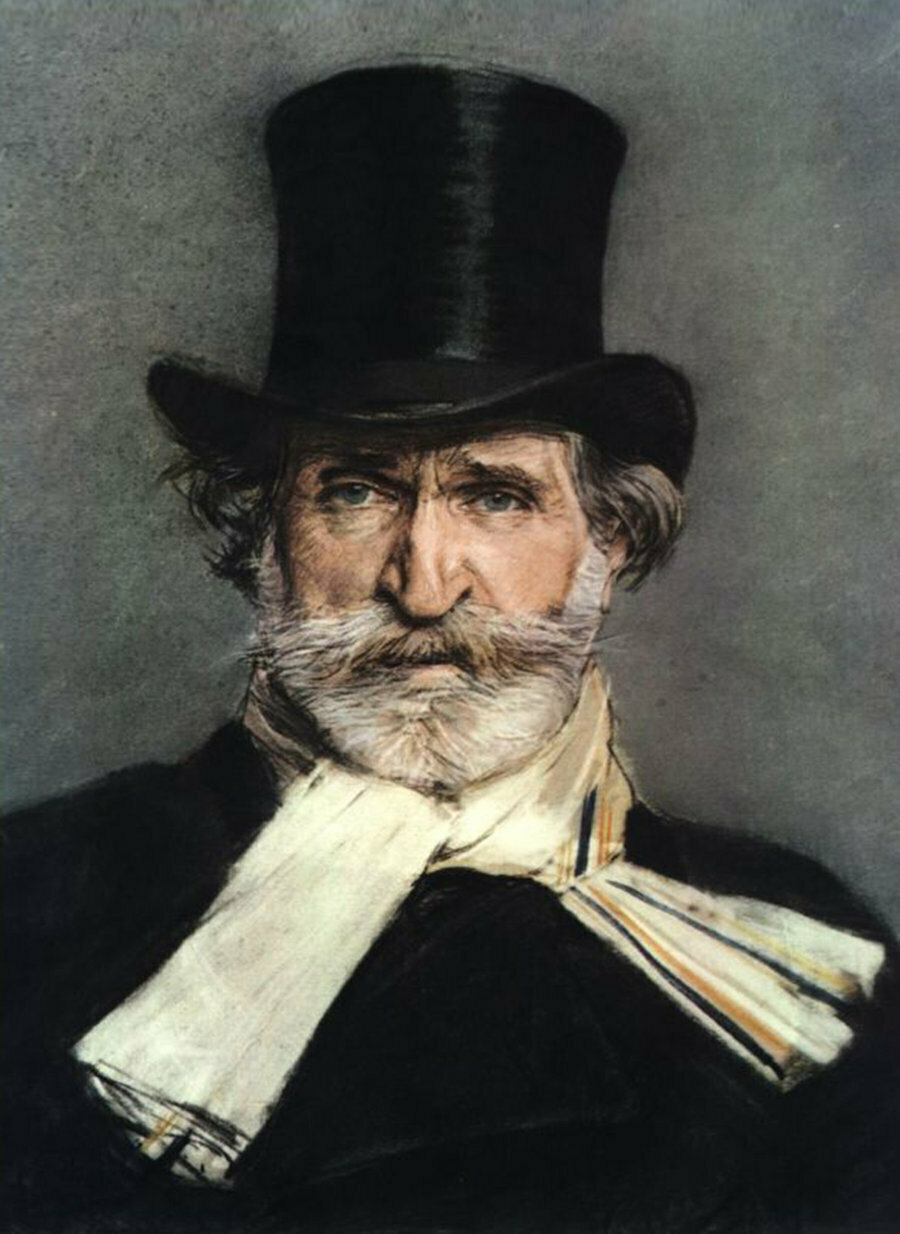

Colin Riley © ComposersEdition

As I duly developed in learning Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and Chopin, one of the piano styles my grandad was keen for me to encounter was ragtime. He bought me a score of The Entertainer and then requested more and more works by Scott Joplin. (Although I never asked him where his enthusiasm for Joplin’s music came from, I have wondered whether my grandad’s 1942 trip across the pond (escorting Winston Churchill during service on HMS Duke of York) either introduced him to it or at least fortified a pre-existing knowledge.) Piano was to my grandfather, as it was to so many of that generation, Liberace, Fats Waller, Jerry Lee Lewis and Winifred Atwell, and the “classical” (if that is indeed the right word) had to orbit amongst other equally “valid” worlds – dixieland, jazz, swing, stride, ragtime. And so, in addition to my father’s huge collection of LPs and singles featuring Elvis, ZZ Top, ABBA and Little Richard, we regularly set spinning the enormously influential release of Joplin’s rags on Nonesuch Records played by Joshua Rifkin.

My grandad embodied the principle of having a healthy respect even for things we do not know. As a child, I repaid his tolerance of Bach with many performances of Joplin; as an adult, I wanted to commission a piece as a tribute to those who have influenced me. As I came to do this in 2018, the question presented itself: how best to memorialise and thank a man who had no musical training or indeed real knowledge of (what we might call) Classical music? And how best to pay tribute to Scott Joplin within my current concerting context?

Joplin Jigsaws © Schellhorn Music Ltd

To achieve this aim, I turned to a composer who in my previous experience would apply artistry, good musical taste and intelligence to the commission, and would – most importantly – imbue the resultant work with the requisite good humour and charm. Colin Riley is a composer whose music has been described as “slightly bonkers” (The Guardian). I was introduced to him in 2009 by another long-time collaborator, Ian Wilson, as a perfect match to write something to celebrate Haydn. He is, to use someone else’s words, a “mid-career maverick” – a musician that I felt could capture (and I say this in the nicest possible way) the simple and naïve attitude towards piano music that my grandad held.

And so the brief for Colin was to take excerpts from Joplin’s works, the ones I played for my grandad, and to mould them into new pieces. Joplin Jigsaws is in seven movements and works with fragments from the pieces I played most to my grandad. Having premiered it in 2018, during lockdown I recorded it informally at Brunel University London; Colin and I leave it to listeners to figure out what the movement titles relate to!

Colin Riley: Joplin Jigsaws (Matthew Schellhorn)

I recently asked Colin Riley to answer some specific questions about his work and specifically this piece:

How much have you written for the piano?

A large part of the creative process involves me sitting at the piano. The tactile nature of composing this way is important to me. Many pieces for larger forces, such as orchestra or large ensemble, begin life “under the fingers”.

Colin Riley © Colin Riley

What tends to happen is that I often develop pieces for piano in the cracks between other works, and so over the last few years I’ve tended to compose quite short pieces that form themselves into a kind of suite. I guess these might be described as character pieces. What I enjoy about this process is that it begins with a small step into the unknown, and then gradually takes form as a larger entity. By the time you have say five short pieces, you automatically know what is needed for another five, and so fashion a satisfying collection. A set of lullabies formed themselves into a collection called While Stars Light Your Way Across The Night. A set of quirky odd-balls of pieces formed themselves more recently into a suite called Ludic Inventions.

There are numerous “early” pieces (that I have not published), but which still have another function; that of being plundered for fresh impetus. Self-plundering is certainly something I find useful. It can be very instinctive, intelligent and rapid. There are some larger works too. Another commission from you found its way on to my NMC chamber album a few years ago: I’m very fond of this piece, As The Tender Twilight Covers for the very reason that it does develop and change over a longer period, and allowed me to paint on a larger canvas.

Have you ever / do you often take pre-existing works as specific inspiration?

You and I met as a result of me composing a short piece for the centenary of Haydn’s death. Weave was a rather cool study in using the letters of Haydn’s name as a basis for motivic manipulation. I think it was very different to all the other pieces in the collection from the other composers. I think mine was very simple and unassuming. The opportunity to go much further with this idea came when you commissioned Joplin Jigsaws. It was a hugely enjoyable piece to write and I think came out rather well!

What were the challenges of writing using fragments of music by another composer?

The main challenge is to ensure that the original motif is recognisable. There are different levels of this of course. In some ways, Joplin Jigsaws is a kind of game. You don’t want to make every question too easy or too hard otherwise people lose interest. As well as this element of the piece, which is essentially to the benefit of the listener, I was able to play my own creative games during the composition of the music. There is always a kind of ‘triangle’ at play when I compose; that of the composer, the performer(s) and the listener(s). The aim for me is to find a ‘sweet spot’. The Joplin motifs that I chose did a lot of the work, to be honest, and so my job became how to ensure that there was a variety of both mood and piano techniques across the whole suite.

What do you think makes Scott Joplin’s music so popular?

I first came across Scott Joplin’s piano rags when I was a teenager. They were a breath of fresh air wafting into my world of classical music. They had that perfect balance of enabling you to sound almost instantly a bit “jazzy”, yet were a serious proposition to play correctly. The left-hand stride techniques took some getting used to, as did the parallel vamping in the right hand. My favourite piece quickly became Bethena.

Scott Joplin: Bethena (arr. R. Docker) (Royal Opera House Orchestra, Covent Garden; Philip Gammon, cond.)

Did what Joplin’s music yield surprise you? Did you find yourself writing differently on account of interfacing with another composer’s music?

In fact, because my music has absorbed many musical genres into its own particular mix, I don’t think this was the case. My music is sometimes described for example as being “a bit jazzy”, and so I was in reasonably comfortable territory composing Joplin Jigsaws.

What techniques other than quotation / reinterpretation do you find yourself returning to as a composer?

I don’t think that I have a prescriptive method of composing. I like to work simultaneously in several mediums. I often contemplate concepts and large-scale ideas in notebooks. I work on the notes initially at the piano using pencil and manuscript. I later work in other parallel mediums like notation software, a digital audio workstation, and on other instruments. I think at the core is my need to be tactile. So much of the time spent seems to be spent on a computer and so this is really important: for the music and for my own sanity. The same is true of the nuts and bolts of generating material and developing that material. I employ a blend of note-spinning procedures mixed with feeling my way instinctively around the piano using hand shapes and muscle memory to guide me. In charge of all this is my ear. That is number one. I do enjoy re-using old material, repotting it and forming something quite different from the original. Not only is this a reassuring way to start, but it also means that I’m putting all my energy into developing and finessing the ideas rather than being obsessed about something new. I’m pleased that when I work in this way, that the result of the repotted music is usually better than the original.

How do the particular properties of the piano lend themselves for new music creation, and on what account do you think the piano is such an influential instrument and an inviting one to write for?

Skin and Wire album by Colin Riley © bandcamp

The tactility is fundamental. I’m a reasonably able pianist and so trying out material in various ways is easy. That said, I’m very conscious of being able to extend the scope of my piano music beyond what I can play and allow the music to live beyond the confines of my own fingers.

I have also been really interested in ways that the piano can be “extended” making frequent use of preparations and electronic manipulation. As a player-composer with my own band MooV this was partly as a way to extend my own abilities, but also to formulate a sonic interest that would blend with the line-up of voice, cello, bass guitar and percussion and provide a kind of musical glue. I have also written a great many works for the multi-piano ensemble Piano Circus where these ideas were honed, allowing for fluid preparations whereby some players could play inside the piano simultaneous to others via the keyboard. This was the case for Double Trio and also some of the works on the album Skin and Wire with drummer Bill Bruford. I took the idea of live electronic processing much further in a piece for Kate Halsall and Fumiko Miyachi called Hanging In The Balance. In this piece, I transferred certain closely mic’ed areas of the keyboard (as well as specific notes) to trigger sympathetic vibrations in percussion instruments scattered around the piano. In this instance they are the parts of a drum kit. This provides both a theatrical and spatial element to the piece as a kind of ghostly ‘accompaniment’ bringing inanimate objects to life through the fingers of the pianist.

What do you hope to encounter when you meet performers and when they commission music from you?

This is one of the best bits of being a composer. I’ve spent much of my working life nurturing trusting and empathic relationships with performers and I feel it is extremely important. I remain hugely touched by the respect given to me by performers. In turn, I like to think that I give something back that honours this trust.

Colin Riley’s Joplin Jigsaws is available to buy from ComposersEdition.

A leading performer for over twenty years, Matthew Schellhorn regularly appears at major venues and festivals throughout the UK and has recorded numerous critically acclaimed albums. Described as a pianist of “searching intelligence and magnificent technique”, he has a distinctive profile displaying consistent artistic integrity and a commitment to bringing new music to a wider audience. In addition to his work on the concert platform, Matthew Schellhorn is a passionate educator and communicator, giving regular masterclasses and workshops in the UK and abroad.He has visited many university music departments and conservatoires to talk about his work in a wide range of performance contexts, including performance practice, commissioning and interpreting new works, working with today’s composers and bringing out fresh ideas in the interpretation of well known repertoire. He maintains a private teaching practice from his home in London. www.matthewschellhorn.com

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter