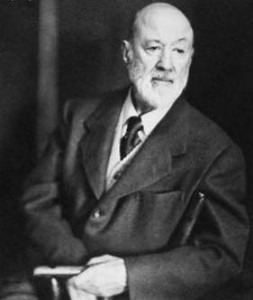

Charles Ives

Ives was born in 1874 in Danbury, Connecticut. His father, who had been a band leader in the US Army during the Civil War, was a strong musical influence on his son. George Ives continued to lead bands after the war and many of the things that Charles Ives put into his music can be traced directly back to some of the things he would have heard during band concerts. His father challenged him with radical ideas in music theory and Ives always credited his father as being his greatest inspiration.

Ives studied the organ and played for a local church from age 14. One of his first and still most impressive organ works is his Variations on ‘America’, which he wrote at age 18. Still considered a challenge for organists, Ives apparently thought it a bit of fun to play. Even at age 18, he was able to put into this work daring compositional elements. We get the familiar melody played as a round – but in two different keys, we get this quintessentially English tune turned into something from Spain with sharp rhythms (and in orchestral performances, those rhythms are played on tambourines and castanets), we get different countermelodies added to the tune, in short, we have a set of variations that is as far from a Beethoven set of variations as we could imagine. Even in the first movement, which sets out the theme, we can hear how much he changes the melody around.

Charles Ives: Variations on ‘America’: I. Allegro (for organ)

Ives: Variations on ‘America’ (orchestrated by William Schuman) Seattle Symphony Orchestra,

Gerard Schwarz, cond.

In the orchestral setting, you can hear the castanets around 04:30 with the melody now in minor.

Central Park at Night

Ives attended Yale University from 1894, studying with the leading American composer of his time, Horatio Parker. He wrote music for Yale, participated in its clubs, and his coach thought that if he abandoned music, he could have a promising career as a sprinter. His senior thesis was his Symphony No. 1. But a life in music was not for him. Upon graduation, he started working for the Mutual Life Insurance Company in New York before moving to an insurance agency. When, in 1907, that agency failed, he and a friend started their own insurance agency, Ives & Co.; he worked there for the rest of his life, leaving it only upon retirement. He is credited with the founding of the modern practice of estate planning, based on his experience in the insurance field.

It was in his off hours that he was a composer and, in fact, after university, few of his compositions were performed during his lifetime. The question of early and late works is often confused by the fact that he kept revising his works for years. One example is his Three Places in New England, which he started sketching in 1903, was composed principally between 1911 and 1914, with the last revisions made in 1929.

Ives was brilliant at conveying a place not only in sound but in effect. One piece of note is his Central Park in the Dark, which puts us in the middle of an evening in New York at the turn of the century: we have the mysterious qualities of the Central Park fauna contrasting with the raucous sound from the surrounding nightclubs, playing the popular hits of the day (listen for “Hello! Ma Baby” and Sousa’s Washington Post March)

Ives: Central Park in the Dark. South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden;

Michael Gielen, cond.

Most of Ives’ compositional work came in the two decades between 1896 and 1916. He stopped composing because, as he told his wife, ‘nothing sounds right.’ He continued on in his revisions, however, and was given the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1947 for his Symphony No. 3 – a work he’d completed 30 years earlier.

It is said that the essence of Ives lies in three elements: juxtaposition of various disparate elements (often leading to a juxtaposition of different key centres), the elements are driven by a narrative that is never fully revealed to the audience, and a tremendous mysteriousness. He’s not always easy to listen to, but he is one of the few composers who, through his juxtaposition of sound, can make you laugh out loud in the middle of a symphony.