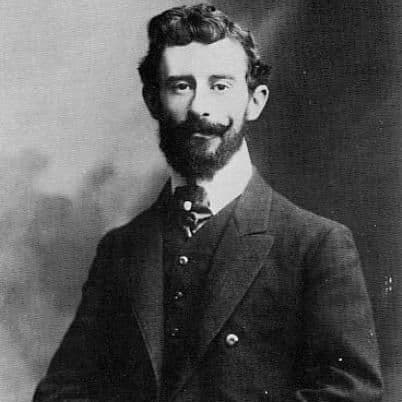

Maurice Ravel was born on the 7th of March 1875, at Ciboure, a little fishing village at the base of the Pyrénées near the French-Spanish border. Members of Ravel’s family on the paternal side had emigrated to Switzerland, and Stravinsky’s sharp but witty barb – that Ravel was “the most perfect of Swiss watchmakers” in music and personality – led to a rather inaccurate association of Ravel with the Swiss by the general public. Indeed, Ravel had greater claims to Spanish roots than Swiss, his mother having spent her youth in Madrid, and his parents having met and fallen in love in Aranjuez, the romantic city known for its summer palace and gardens, as well as the concerto for guitar and orchestra, Concierto de Aranjuez.

Maurice Ravel

Shortly after Maurice was born, the family relocated to 40 rue des Martyrs, Montmartre, Paris. Soon, the happy couple had a second son, Edouard, of whom Ravel was deeply fond for his entire life. For, indeed, it was a happy little family – Ravel was exceptionally close to his mother, and Ravel’s father, a skilled engineer, was only too happy to encourage Ravel in his artistic pursuits. Edouard followed in his father’s footsteps and became an engineer, but on both sides of the family – the engineers and the artists – there seemed to be mutual interest and respect. Ravel noted in later years that his father had given him a strong amateur grounding in music and artistic taste, and in his music-related travels, Ravel was always sure to send news to his father and brother of any interesting technology he encountered.

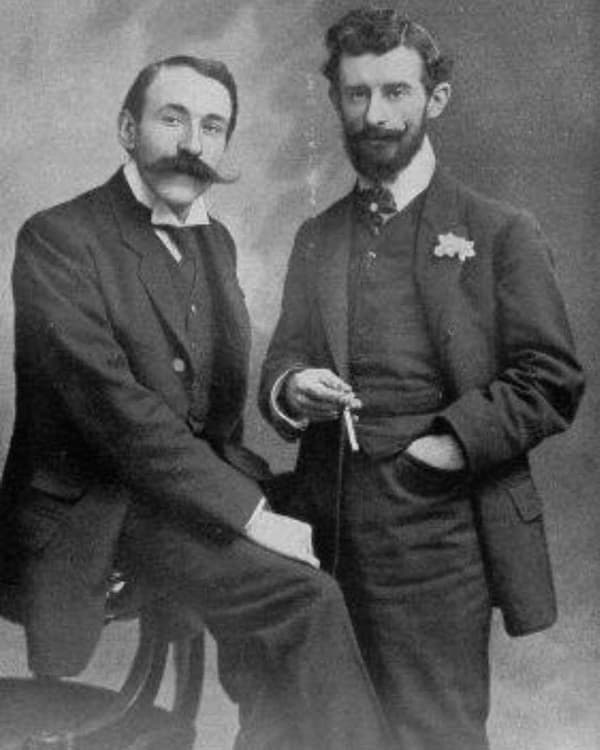

In 1889, Ravel passed the entry exam to study piano at the Paris Conservatoire, and in the class of Eugène Anthiome met a key player in the story of his life and work. Ricardo Viñes, a young pianist who would one day become a leading interpreter of the music of Isaac Albéniz and Manuel de Falla, became fast friends with the young Maurice, and a tradition was born: their mothers would chatter away in Spanish while the young boys played piano duets. It was to Viñes that Ravel’s Menuet antique was dedicated, and Viñes premiered it at the Salle Érard in 1898.

Maurice Ravel: Menuet antique

On the whole, however, Ravel’s experience of the Conservatoire was not an entirely smooth one. He remained at the Conservatoire for fourteen years, an unusually long time. He was not one to seek academic distinction for its own sake, and his resistance to conventional ideas and the imposition of others upon his style created various difficulties in entering and competing in the illustrious Prix de Rome on numerous occasions.

While he did win prizes for piano and advanced to better classes in both piano and harmony, Ravel began to feel he had learnt what he could from the Conservatoire, and was expelled for this attitude in 1895 – the first of several expulsions for failure to adhere closely to the Conservatoire’s rigid rules. It was in studying with composer Gabriel Fauré that Ravel found a way of being at the Conservatoire that truly suited him, and the composer became a treasured friend and mentor when Ravel renewed his studies in 1898.

Maurice Ravel with Ricardo Viñes, 1901

In addition to Fauré, at a young age, Ravel had already identified three musical figures who were his greatest compositional inspirations: Emmanuel Chabrier, Erik Satie, and Mozart. In a lecture given in 1928, Ravel said of Satie:

“Satie possessed an extremely alert intelligence, keyed to inventiveness… [he] pointed the way with simplicity and ingenuity; but as soon as another musician followed his lead, Satie immediately changed his own direction and then, without hesitation, opened a fresh way to new fields or experiment… we have today… many a work which would not have existed had Satie not lived.”

Ravel’s next work to be premiered for the public was his Shéhérazade, an overture to a projected but abandoned opera, and his first work for orchestra. The work was not well received, and Ravel himself dismissed it as “clumsy hotch-potch.” His next serious commission has become one of Ravel’s best-known and beloved works: the Pavane pour une infante défunte. For solo piano and dedicated to his patron, the Princesse de Polignac, the piece is not, as many incorrectly assume, a pavan for a deceased child. Rather, the “enfant” here refers to “infanta,” or princess, and the “défunte” refers less to literal death than to a bygone age or the distant past. As such, the work is a kind of otherworldly, surreal imagining of the dance of a princess of a lost age, and Ravel often wittily chided pianists who played it too slowly by saying it was the princess, not the pavane itself, that was dead. The work is incredibly harmonically rich and showcases Ravel’s profound understanding of the timbral qualities of chord spacings at the piano. Its charm, carefully constructed inner voicings, and delicate interplay of line have made it an enjoyable and accessible challenge for generations of pianists.

Maurice Ravel: Pavane pour une infante défunte (version for piano) (Angela Hewitt, piano)

In the pavane we also see emergent preoccupations that were to be Ravel’s for the rest of his life – his enjoyment of old dance style and form, his fascination with the heritage of both Spain and France, and his deliberate assimilation of arcane soundworlds into his musical style. At the turn of the century, armed with a strong sense of his own musical interests and sensibility, Ravel was poised and ready to earn his lifelong stature as a great composer – but there were still some bumps in the road ahead…

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Hello. I am new here from Slovenija.

I played piano when young girl.