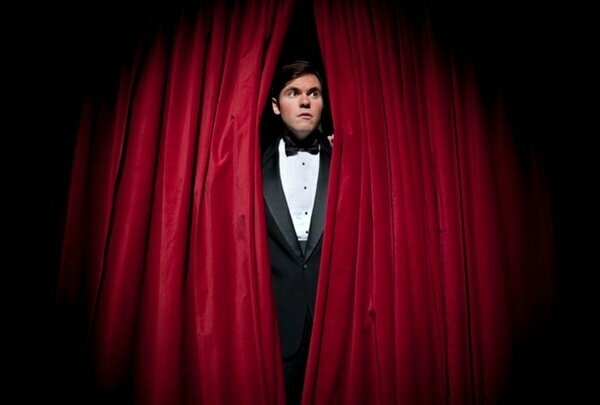

Herbert von Karajan conducting Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5

© Berliner Philharmoniker Digital Concert Hall

Everyone will have an opinion on this – do you want the traditional German heavy recordings? The new interpretive English opinions? Do you want national orchestras? Idiosyncratic readings that make you hear old warhorses with a new manner of understanding? Join us in an exploration of the audio world of Beethoven.

Symphony No. 1-9

The first conductor to record a full Beethoven cycle was the German conductor Herbert von Karajan, and then he went onto record three more full cycles. The first was in 1951-55 with the Philharmonic Orchestra, and then with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1961-62, 1975-76, and then 1982-84. Four decades of recordings give us an idea of the changes in thinking in the 20th century of these works. Karajan gives us classical interpretations that took decades to rethink.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21 – I. Adagio molto – Allegro con brio (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

As a full cycle, Nikolaus Harnoncourt with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe meets all our expectation and then goes beyond. From the first movement of the first symphony, which has a fine delicacy often missed, to the too-familiar opening of the fifth, which is given an expansiveness rarely heard, to the final of the ninth, we’re given a performance that both benefits from Harnoncourt’s historical studies and is informed by so many of the recordings that already exist.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21 – I. Adagio molto – Allegro con brio (Chamber Orchestra of Europe; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

What is it, however, that you’re listening for? In Wilhelm Fürtwangler’s 1954 recording of the Symphony No. 1, his opening is almost tentative. Slow and deliberate, he eases us into Beethoven world. When you compare it with the 1982 Beethoven above, there’s an authority we don’t hear in Fürtwangler’s recording. It’s equally slow and deliberate, but without that tentative feeling.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21 – I. Adagio molto – Allegro con brio (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Wilhelm Furtwängler, cond.)

Pierre Boulez © Deutsche Welle

One of the great test sections of Beethoven is the opening of his Fifth Symphony. How does the conductor hear that? Separate statements? A stuttering start? An overarching declaration? A rushed trope to get through? Different performances take it in different directions. The great ones, though, give it a majesty that sets the tone for the rest of the movement.

Pierre Boulez, with the New Philharmonia Orchestra in 1968, gives us an opening of startling gravity. As one reviewer noted “the tempo is wrong (for once, Boulez has overridden the composer’s marking) but the performance is very powerful indeed, rhythmically driven and ultimately overwhelming.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 – I. Allegro con brio (New Philharmonia Orchestra; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

Leonard Bernstein’s No. 5, with the New York Philharmonic, is a more classical rendering. Not too slow, not too fast, but with an appreciation of the style that Beethoven is giving him to play with. After the opening, listen in particular to the oboe solo at 05:17. There’s a beauty there that’s rarely heard.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 – I. Allegro con brio (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

Roger Norrington conducting the Orchestra of St. Luke’s and the Oratorio Society of New York at Carnegie Hall. © Ian Douglas for The New York Times

To me, one of the most overrated concepts of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is that it is for an infinitely large orchestra with an infinitely large choir. I’d love to hear it with a rationally sized orchestra and a choir that goes for clarity rather than the shouty version that seems to be the norm. Remember when Joshua Rifkin took Bach’s B minor Mass and made it into what was referred to as the “B minor Madrigal” by cutting the choir down to 8 singers? Why can’t we do the same with Beethoven’s Ninth?

The closest I’ve been able to find is Roger Norrington’s recording with the London Classical Players and the Schütz Choir.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, “Choral” – IV. Finale: Presto (London Classical Players; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Compare this with Karajan’s recording with The Vienna Symphony and the Wiener Singverein and soloists. The choir is just a miasma of sound. All you can hear are the vowels, howling behind the orchestra.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, “Choral” – IV. Finale: Presto (Lisa Della Casa, soprano; Hildegard Rössel-Majdan, mezzo-soprano; Waldemar Kmentt, tenor; Otto Edelmann, bass; Wiener Singverein; Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

Perhaps the problem is the familiarity. We know the work and its sound too well; we want to be part of the giant extravaganza. Symphony No. 9 required the largest orchestra that Beethoven had ever written for and maybe we’ve taken that as the key to continually raise the bar of the number of performers on a stage. But with the Ninth as with any Beethoven symphony, approach it with an understanding of what YOU want to hear. Delicate and understated? Massive and loud? Tickling your sensibilities or moving you to your very core? Beethoven is all of that and using only the symphony performances, you can find your own private Beethoven.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

No Kleiber. You are surely joking.

Agreed! Though he did not record the full cycle for release, #’s 5 &7 especially deserve mention.

Von Karajan was not the first conductor to record a full cycle. Weingartner was, back in the 1930s.

Has Toscanini been deliberately omitted from ” the best” categories of Beethoven recordings? While the recording of AT were at a time when sound recordings were primitive by todays standards , the actual interpretations were quite remarkable