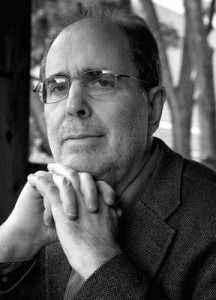

Joshua Rifkin

Credit: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/

In 1981, musicologist and performer Joshua Rifkin proposed a radical idea: that Bach’s B Minor Mass (and, in fact most of Bach’s choral works) be performed not with massive choir, but with the smallest possible choir, with one singer per part. His argument is that what we think of as the modern chorus did not exist in Bach’s time. This idea of one singer per part got his work the nickname “The B Minor Madrigal.”

Before Rifkin’s ground-breaking proposal, much of Bach’s choral music has traditionally been performed in a manner similar to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony: soloists and a big chorus. Scholars did admit that a giant version, such as Mendelssohn’s revival of the St. Matthew Passion, for example, with a choir of nearly 160 singers in 1829, carried the big chorus idea too far. Many choirs might reduce the chorus to as few as 3 or 4 voices per part (for a chorus just under 40 singers) but Rifkin’s contention that this music was of such difficulty and such complexity that, in Bach’s time, it could only be sung with one person per part for a total of 8 singers.

When we start to look at various recordings of the mass, we can hear Rifkin’s point very quickly. We will be comparing a standard recording by The Robert Shaw Chorale from 1960 and Rfikin’s 1981 recording with The Bach Ensemble.

In listening here to the opening Kyrie, we can hear the differences immediately:

Bach: Mass in B Minor: Kyrie I (Robert Shaw Chorale; Robert Shaw Orchestra; Robert Shaw, cond.)

Bach: Mass in B Minor: Kyrie I (Judith Nelson, soprano; Julianne Baird, soprano; Jeffrey Dooley, counter-tenor; Drew Minter, counter-tenor; Frank Hoffmeister, tenor; Edmund Brownless, tenor; Jan Opalach, bass; Andrew Walker Schultze, bass; The Bach Ensemble,; Joshua Rifkin, cond.)

The sound is clearer, the vocal lines more distinct, and the lyrics more clear. And, since this is music for a religious ceremony, it’s all about the words.

If we look at a later part of the mass, the Laudamus te, written for solo soprano, we’ll hear other differences.

Bach: Mass in B Minor: Laudamus te (Adele Addison, – soprano; Robert Shaw Orchestra; Robert Shaw, cond.)

Bach: Mass in B Minor: Laudamus te (Julianne Baird, soprano; The Bach Ensemble,; Joshua Rifkin, cond.)

The first thing you’ll hear in the Rifkin recording is the result of the modern work on performance technique – her trilling is lighter than on the Shaw recording, and ends up being better at conveying the meaning of the words (We praise You).

Rifkin’s work has been influential in many new recordings of Bach’s works, such as Sigiswald Kuijken’s recording with La Petite Bande.

Bach: Mass in B Minor: Kyrie I (Gerlinde Saemann, soprano; Patrizia Hardt, mezzo-soprano; Petra Noskaiova, alto; Bernhard Hunziker, tenor; Niedermeyr, Marcus- bass; La Petite Bande; Sigiswald Kuijken, cond.)

John Butt and the Dunedin Consort’s 2010 recording, Konrad Junghänel’s 2004 recording with Cantus Cölln, and many other recordings carry Rifkin’s idea forward, so that now we have to think of Bach not as an overblown 19th century phenomenon but as a most delicate master working with singers who were consummate musicians in their own right.

“And, since this is music for a religious ceremony, it’s all about the words.”

Was the B-minor composed for a religious ceremony? I very much doubt it.

For me the proof of the pudding is in the eating and the B-minor madrigal (I had the misfortune to attend a performance by some very highly-regard early music specialists 18 months ago) comes across as very good music.

But it is actually a supreme masterpiece and needs to sound like it.

My favourite performance remains Karl Richter’s from 1961. Not a huge choir, but still a choir dammit.

The smaller choral forces is one of the reasons I loved the Rober Shaw Chorale’s version of Handel’s Messiah (recorded in 1966), with not 200, 100, or 50, but only 31 voices in the choir. Such clarity and vitality.

1 voice per part is too small. I prefer Andrew Parrott’s use of 2 per vocal part so certain sections can be reinforced. But in this sort of configuration, the acoustics of the space is crucial. Something mentioned in Parrott’s book on this is that perceived loudness is logarithmic so to get double the volume you would need 3 or 4 per vocal part. Also very likely in Bach’s time and definitely in Brahm’s time, the singers were placed in front and not back behind the orchestra like they are today.