“Fine and Delicate Taste Is the Fruit of Education and Experience”

Ingres’ violin in the Ingres Museum in Montauban

The popular French expression “le violon d’Ingres” essentially makes reference to a secondary skill or hobby, that is, an activity done in one’s leisure time. This figurative term originated from the obsession of French neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres for playing the violin. Ingres was a passionate violinist from his youth, and he even played second violin in the Orchestre du Capitole in Toulouse.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

During his time at the French Academy in Rome he frequently performed with guest artists and music students, including Charles Gounod. Gounod, in fact, wasn’t really impressed and wrote, “He was not a professional, even less a virtuoso.” Apparently Ingres performed Beethoven string quartets with Niccolò Paganini, and Franz Liszt described his playing as “charming.” We don’t know if Ingres ever played all the Mozart and Beethoven violin sonatas with Liszt, but we do know that Liszt dedicated his transcriptions of the 5th and 6th symphonies of Beethoven to Ingres. Ingres’ actual instrument was bequeathed after his death, together with a series of paintings, to his native town of Montauban, near Toulouse.

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 4 in C minor, Op. 18, No. 4

Ingres: Niccolò Paganini (1819)

As the saying goes, it wasn’t music that made Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres famous; it was his primary occupation as a painter who guarded academic orthodoxy against the rising Romantic style. “With a daring blend of traditional technique and experimental sensuality, Ingres reimaged Classical and Renaissance sources for 19th century tastes.” An impeccable draftsman known for his serpentine line and illusionist textures, “Ingres was at the center of a revived ancient debate that questioned whether line or color was the most important element of painting.”

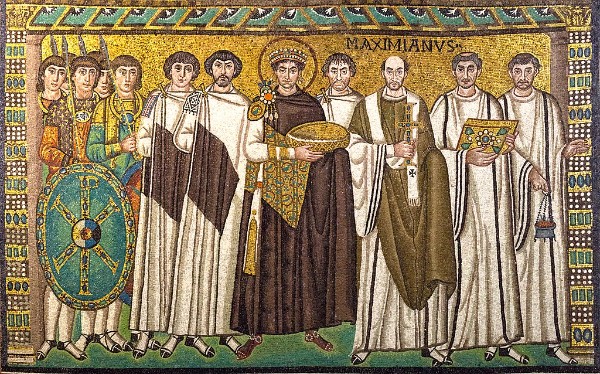

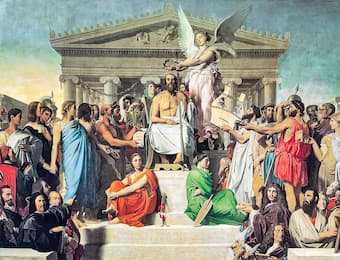

Ingres: The Apotheosis of Homer

Ingres was born the eldest son of the sculptor, painter, and musician Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres. His musical and artistic talents were immediately recognized, and his father sent him first to Toulouse to study with the painters Guillaume-Joseph Roques and Jean Briant, and with the sculptor Jean-Pierre Vigan. Leaving for Paris in August 1797, Ingres entered the studio of the illustrious neoclassical master, Jacques-Louis David. Determined to make his name, Ingres dedicated himself to history painting by selecting his subjects from Greek mythology. While his paintings still center on the classical male nude, his narrative, however, turns towards “the complicated psychologies of Romanticism.”

Franz Liszt: “Beethoven Symphony No. 6” – V. Allegretto (Shepherd’s song: Feeling of thankfulness after the storm) (Konstantin Scherbakov, piano)

Ingres: The Vow of Louis XIII

Ingres won the coveted Prix de Rome on his second try and departed for his residency in Rome in 1806. He swore that he would not return to Paris until he was acknowledged as a serious and important history painter. While adhering to academic conventions, Ingres started to experiment with more emotionally evocative and sensuous subjects, including the tradition of the female nude.

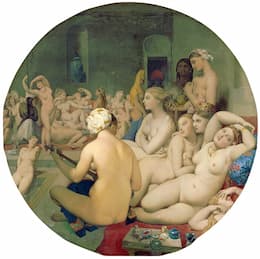

Ingres: Le Bain turc

The reclining woman had been a popular motif since the Renaissance, and Ingres continues that “tradition by drawing the figure in a series of sinuous lines that emphasized the soft curves of the body. However, Ingres was painting the idealized human form by distorting the bodies.” His “La Grande Odalisque” of 1814 “needed two or three extra vertebrae to achieve her dramatic and twisted pose. The figure’s legs seem out of proportion, with the left improbably elongated and disjointed at the hip. The result is paradoxical, as she is at once strikingly beautiful and eerily strange.” This newly found freedom of emphasizing graceful contours and pleasant visual effect “encouraged other artists to take liberties with the human form, from Renoir, who was reportedly infatuated with Ingres, to the 20th century Surrealists.” Critics predictably found his style bizarre and archaic, and for a while Ingres had to support himself as a portrait painter.

Charles-François Gounod: String Quartet No. 2 in A Major (Quatuor Danel)

Ingres: Grande Odalisque

Ingres did make his triumphant return to France with the 1824 monumental altarpiece for Montauban Cathedral, “The Vow of Louis XIII.” Finally recognized by the Salon, Ingres was “acknowledged as the undisputed leader of the Neoclassical school in France.” Ingres was now seen as the chief defender of the classical tradition and in clear opposition to the emerging school of Romanticism as practiced by Eugène Delacroix.

Ingres: Oedipus and the Sphinx

He did receive the Cross of the Legion of Honor from Charles X, but his painting for the cathedral at Autun was sharply criticized for its “dark tonalities, disorderly composition, and the anatomical distortions of his figures.” Always temperamental and exhibiting a flair for the dramatic, Ingres returned to Rome to take on the directorship of the Académie de France. Ingres vowed to never exhibit his work in public again, but relented for an 1846 retrospective of his teacher Jacques-Louis David. In 1855 he was honored with a monographic retrospective and a gallery devoted entirely to him at the Exposition Universelle. However, Ingres was outraged of having to share the grand Medal of Honor with nine other artists, including Delacroix whom he called the “apostle of the ugly.”

Ingres spent the last decade of his life in “revisiting old motifs and long-abandoned canvasses,” and he died of pneumonia on 14 January 1867. His influence extended to Édouard Manet, Gustave Moreau, and Pablo Picasso, “inspiring the Symbolists and Surrealists with his combinations of the familiar and the peculiar”. The 21st century, in turn, has criticized Ingres “as the chief representative of retrograde art-making practices that exploited the female nude to a male gaze and have taken issue with his eroticized, colonialist subjects.”

Ingres spent the last decade of his life in “revisiting old motifs and long-abandoned canvasses,” and he died of pneumonia on 14 January 1867. His influence extended to Édouard Manet, Gustave Moreau, and Pablo Picasso, “inspiring the Symbolists and Surrealists with his combinations of the familiar and the peculiar”. The 21st century, in turn, has criticized Ingres “as the chief representative of retrograde art-making practices that exploited the female nude to a male gaze and have taken issue with his eroticized, colonialist subjects.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Violin Sonata in E minor, K. 304