Dancer, actress, and arts patron Ida Rubinstein was a trailblazing figure in the arts, and her impact on early twentieth century music was profound.

A gifted performer, she knew how to captivate audiences with her beauty, stage presence, and creative moxie.

Whether starring in controversial productions or commissioning classics like Ravel’s Boléro, Rubinstein’s influence extended far beyond the stage and continues to resonate even today.

Great Wealth and Great Tragedy

Ida Rubinstein, 1912

Ida Rubinstein was born in October 1885 in Kharkov in present-day Ukraine, the youngest of the four children of Lev Rubinstein and his wife Ernestina.

The Rubinsteins were a hugely wealthy family, overseeing mills, breweries, and banks.

However, their extraordinary wealth couldn’t insulate them from tragedy. Ernestina died in 1888, then Lev died in 1892, possibly of cholera.

After their parents’ deaths, the Rubinstein children were split up. Ida and her sister Irène were relocated to St. Petersburg to live with an aunt.

She received a wide-ranging education that focused heavily on the arts and languages. The arts and arts philanthropy were hugely important to the entire family. (In fact, her cousin Iosif studied piano under Liszt.)

Finding Her Way to the Stage

Ida Rubinstein in tutu

As a young woman, faced with the prospect of entering the marriage market, she decided she wanted to pursue a life on the stage instead.

She studied theater for a few years in both Moscow and St. Petersburg.

In 1904, when she was just nineteen, she mounted and starred in a production of Sophocles’s Antigone, casting herself in the title role.

She hired painter and costume designer Léon Bakst for the project. He told her to start her career small and smart: to only present one act, and to do so privately.

The advice was sound. Her private performance was a major success, and Rubinstein proved to be incredibly talented and magnetic.

She also, fatefully, began studying dance. Despite her relatively advanced age, dance quickly became her major passion.

She had begun too late to become a great technician – or even a good one – but her charisma, grace, beauty, and stage presence made up for it.

Bringing a Controversial Salome to Life

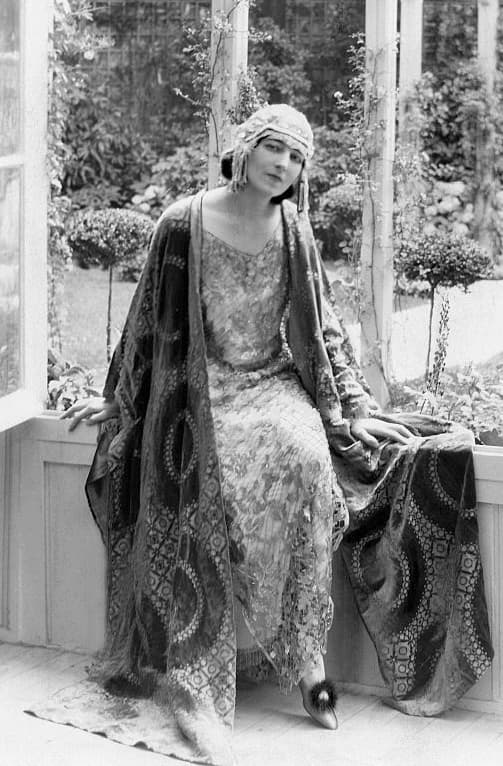

Ida Rubinstein, 1922

In 1908, she caused a succès de scandale in St. Petersburg, when she appeared in an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s Salome.

The performance was banned by the Orthodox Church, the official state censor. The performers got around that by miming the entire performance.

The role offered her the opportunity to dance the highlight of the show: the Dance of the Seven Veils, performed to newly composed music by Alexander Glazunov. Her choreographer for the number was Michel Fokine, famous for choreographing The Dying Swan, Les Sylphides, Scheherazade, The Firebird, and countless other classics.

Alexander Glazunov: “Dance of Salome” op.90

One contemporary described her gamble:

Never before had the St. Petersburg public been treated to the spectacle of a young society woman dancing voluptuously to insinuating oriental music (composed by Glazunov), discarding brilliantly colored veils one by one until only a wisp of dark green chiffon remained knotted round her loins. Although, as Alexandre Benois revealed, this final and reprehensible moment of the dance was dissimulated by means of a lighting trick.

Not surprisingly, her family was horrified and desperately wanted to rein her in. To ensure that none of them would have the power to take legal action against her, she married a cousin named Vladimir Gorvits.

Joining Forces with Diaghilev

Ida Rubinstein in Le Martyre de saint Sébastien, 1911

Choreographer Serge Diaghilev of the legendary Ballets Russes took notice of the striking young socialite with the penchant for nudity.

He cast her in the new ballet Cléopâtre, a work choreographed by Fokine and featuring music by Anton Arensky. She traveled to Paris and donned the see-through costume with great enthusiasm.

Anton Arensky: Egyptian Nights

Despite her lack of training, she enthralled enchanted audiences.

She returned in the 1910 season in a ballet made up of music from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 symphonic suite Scheherazade.

That success was even greater than Cléopâtre had been, and it altered the course of music, design, and fashion for years to come.

‘Scheherazade’ / Svetlana Zakharova and Farukh Ruzimatov / Mariinsky Ballet in Paris

Striking Out on Her Own

Rubinstein could have continued with the Ballet Russes, but chose not to so that she could pursue her own projects.

Diaghilev became irritated with her. She had seemingly endless amounts of money at her disposal and could hire his greatest artists out from under him. He remained bitter about their relationship until his death.

After leaving the Ballet Russes, Rubinstein branched out on her own to produce the wildly ambitious Le Martyre de saint Sébastien.

This was a musical mystery play that she commissioned and produced, featuring a text by Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio and incidental music by Claude Debussy. Fokine returned to choreograph.

Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas describes Le Martyre de saint Sébastien

Rubinstein gender-bent the role, appearing as an androgynous St. Sebastian. Not surprisingly, that casting caused dismay among conservative factions. In fact, the archbishop of Paris warned potential Catholic theatergoers not to attend because she was both Jewish and a woman.

Unfortunately, the five-hour-long project was rushed, resulting in a lack of narrative cohesiveness, and despite her best wishes and the geniuses attached to the project, Le Martyre was not a success.

Debussy : Le Martyre de saint Sébastien

In 1928, she established her own ballet company, Les Ballets Ida Rubinstein. She would commission important works over the following years from a variety of composers.

Igor Stravinsky’s “Le baiser de la fée”

In 1928, she commissioned Stravinsky to write a ballet using Tchaikovsky’s music. The result was “Le baiser de la fée.”

Stravinsky: “Le baiser de la fée”

Stravinsky wrote to a friend whom he sent the piano score to:

Don’t show it to Ida, Nijinsky or Benois. It is necessary for people such as they are – not particularly initiated – that I play the music for them myself.

Diaghilev was deeply upset with Stravinsky for having accepted a commission from Rubinstein after he’d pulled back from Diaghilev.

“He would not forgive me for having accepted Ida Rubinstein’s commission, and he was loud, both privately and in print, in denunciations of the ballet and of me,” Stravinsky wrote later.

Stravinsky conducted the premiere at the Paris Opéra in 1928. Rubinstein only arranged for a single performance, to Stravinsky’s irritation: he was bewildered that anyone would spend thousands of dollars on such a venture. “Nobody in the artistic world is as mysteriously stupid as this lady.”

Despite his misgivings, her money talked. He reunited with her for 1934’s Perséphone, a work for speaker, singers, dancers, and orchestra.

Stravinsky: Perséphone

Maurice Ravel’s “Boléro”

In 1927, Rubinstein approached Maurice Ravel about creating a work for her.

He had his heart set on arranging some Spanish dances by Albéniz’s Iberia. However, he found out that another composer had the rights to the music, and that his project would be impossible to carry out. He complained, “The laws are idiotic. What am I going to tell Ida?”

He came back with what would become one of the most popular pieces in classical music history: the fifteen-minute long Boléro.

She negotiated exclusive rights to Boléro for three years in theaters and one year in concert halls.

Ravel: Boléro | Alondra de la Parra | WDR Symphony Orchestra

At the same time, she resurrected Ravel’s orchestral tone poem La Valse, which Diaghilev had famously dismissed as “a masterpiece” but “not a ballet. It’s a portrait of ballet.” (This remark soured the formerly fruitful relationship between Ravel and Diaghilev once and for all.)

Ida Rubinstein disagreed with Diaghilev, and hired Bronislava Nijinska to choreograph it. In the late 1920s, she successfully presented Boléro and La Valse on the same program.

La Valse – Corps de ballet (The Royal Ballet)

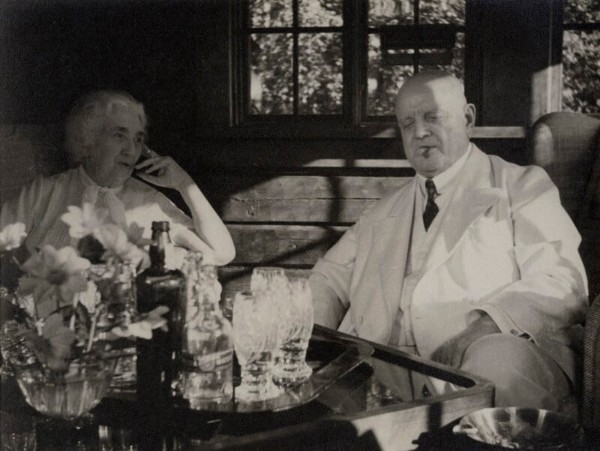

In 1932, Ravel was in a terrible taxi accident that left him with brain damage. It became increasingly difficult for him to compose and even to go about his daily life. Ida paid for a trip for him and a friend to visit Spain and Algiers, hoping it would improve his health.

The Legacy of Ida Rubinstein

In addition to her incredible contributions to the repertoire, it’s worth noting Ida Rubinstein’s famous free spirit.

She was always impeccably dressed in the latest fashions. She had romantic relationships with both men and women. She loved going on big game hunts and even living amongst wild cats. For a while, she kept a leopard cub and even a panther in her apartment. The panther once came close to attacking Diaghilev. He was bitter about that.

Ida Rubinstein retired to the south of France in the 1930s and died in 1960.

Historical opinion on her is mixed.

On one hand, it is believed that she was self-indulgent and perhaps a little too eccentric for her own good.

Simultaneously, no one can deny the number of masterpieces that she ushered into the world. Few wealthy people in the history of classical music have used their resources to bring so much musical joy to so many people.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter