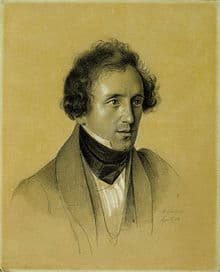

Mendelssohn was only 26 when he took up his appointment as Director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1835. Mendelssohn was internationally famous, and Schumann, who had just founded the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, was still struggling to find his way as a composer. When Schumann discovered Schubert’s “Great” Symphony in C in Vienna, Mendelssohn performed it, and he also premiered Schumann’s “Spring Symphony.” The young Clara Wieck, both before and after her marriage to Schumann, performed frequently in the Gewandhaus concerts with Mendelssohn conducting. Mendelssohn and Robert and Clara Schumann had a close working relationship, yet there seems to have been some tension between Felix and Robert.

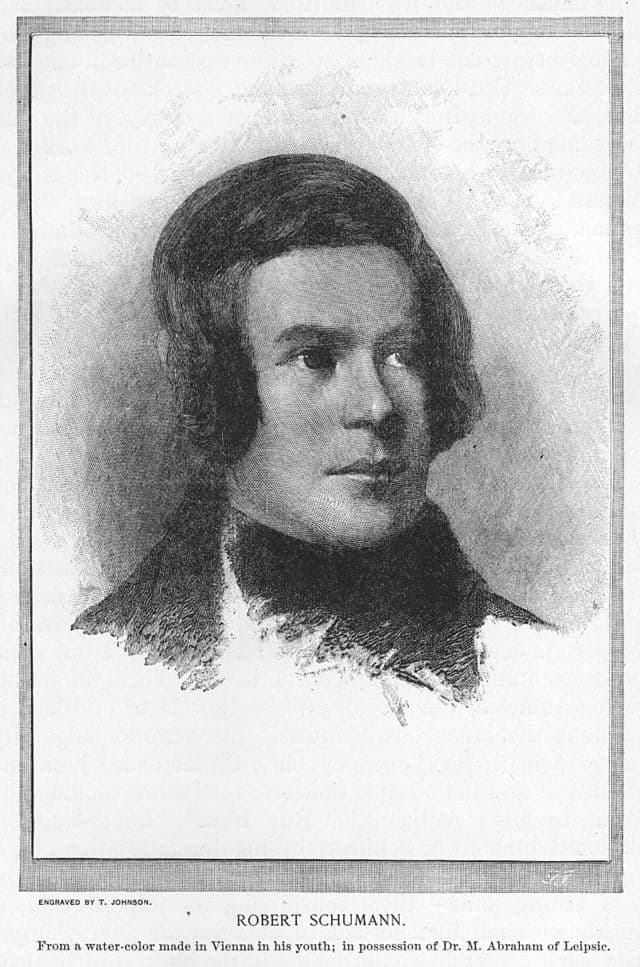

Robert Schumann in youth

Robert bestowed high praise on Felix, but everybody was surprised that Felix doesn’t mention Robert at all in any of his published correspondence. While probably not the best of friends, they clearly respected each other professionally. And when Mendelssohn was asked to organize the establishment of a new conservatory in Leipzig, Robert Schumann was hired to teach piano and score reading. In turn, Schumann was one of the pallbearers at Mendelssohn’s funeral.

Felix Mendelssohn: String Quartet No. 6, Op. 80 (Quatuor Ébène)

Babette Salomon, Mendelssohn’s grandmother lived in Paris, and she had a good friend who collected old music manuscripts. Babette managed to find a copy of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, and she passed it on to Felix. Apparently, Mendelssohn went over the score again and again, and he made notes in the margins and carefully copied out sections.

Bach’s St. Matthew Passion

During the next couple of years, Mendelssohn asked his friends to sing some of the parts, and Therese Devrient remembered, “Felix would sit at the piano, pale and excited. We the singers stood around him so that he could at all times see us… We were terribly moved and felt that we had been transported into a new world of music.” Her brother Eduard Devrient (1801-1877), who had previously sung the role of Carrasco in Mendelssohn’s only publicly performed opera Die Hochzeit des Camacho, was so excited by the power of the music that he told Felix that they had to perform the entire work in public; Felix would conduct, while Eduard would sing the central role of Jesus. And thus, the revival of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion took place in 1829 as planned.

Eduard Devrient

Eduard Devrient published his memoirs in 1869, which reveal his affection and sympathy for Mendelssohn as well as the likely influence on his later friend and collaborator Richard Wagner.

Felix Mendelssohn: 3 Motets, Op. 39, No. 3 “Surrexit Pastor Bonus” (St Albans Cathedral Girls Choir; Peter Holder, organ; Tom Winpenny, cond.)

The son of the English glee composer William Horsley, Charles Edward Horsley (1822-1876) first met Mendelssohn in 1832 in London. Horsley quickly decided to study in Germany, and by 1841 he had moved to Leipzig for composition lessons with Mendelssohn. When his instruction ended in 1843, he returned to London and stayed in touch with his old teacher and friend.

Charles Edward Horsley

In fact, Mendelssohn was a frequent visitor to the Horsely estate. He writes, “Mendelssohn used to come to us at all times when in London, and especially to breakfast, generally accompanied by his friends Rosen and Klingemann. We had a small garden attached to my father’s house, and it was Mendelssohn’s great delight to spend hours in this, sketching the trees, and talking not only about music, but about his travels in Italy, his intimacy with Goethe and Zelter, and his future plans for his works. During these mornings we frequently heard the first germs of compositions that have now become immortal. The beautiful overtures to “Melusine” and “Isles of Fingal” were played at Kensington some years, I may say before they were performed, and my sister possesses a copy of the first MS. totally different from those now published.”

Felix Mendelssohn: Overture “Die schöne Melusine” (Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra; Kurt Masur, cond.)

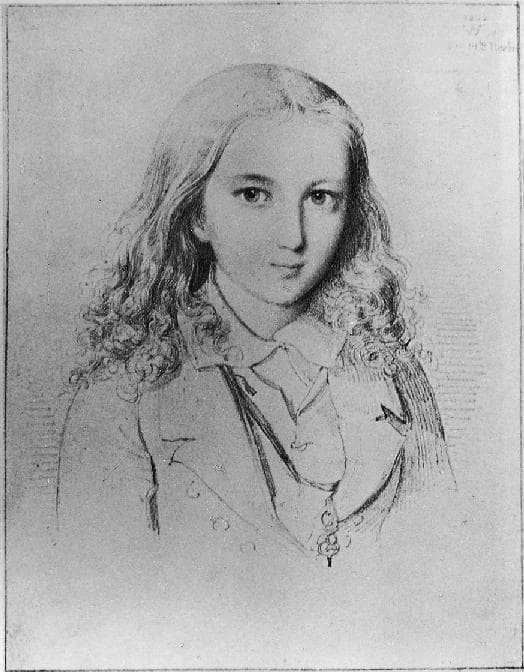

Fanny Mendelssohn

Inexorably drawn together by their common extraordinary talents and profound love for music, Felix Mendelssohn and his older sister Fanny Mendelssohn (1805-1847) developed a close relationship that endured throughout their lives. In fact, Felix would regularly submit his compositions to his big sister, and taking her critical advice to heart, never hesitated in modifying or deleting material that she found questionable. Both started composing at an early age, and music took a central stage in the Mendelssohn household.

William Hensel: Portrait of Felix Mendelssohn, 1822

According to a contemporary critic, “Felix wrote technically superior compositions, but Fanny’s expressiveness was unmatched.” Fanny, in turn, developed a protective and almost motherly attitude towards him in their early years. In hundreds of letters, she became her brother’s muse, best friend, and chief critic, discussing new pieces and providing lengthy assessments of major works. These letters not only chronicle the diverse phases of their adult years but also disclose a relationship of far-reaching personal and musical consequences.

Felix Mendelssohn: Concerto for 2 Pianos in E Major, MWV O5 (Katia Labèque, piano; Marielle Labèque, piano; Philharmonia Orchestra; Semyon Bychkov, cond.)

Carl Friedrich Zelter

Scholars have noted that Felix Mendelssohn “was well educated, privileged since childhood by money and all the access money could purchase.” And it was family wealth that permitted Felix to study with Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758-1832). While Zelter was primarily known during his lifetime as a composer, conductor, and teacher, his greatest legacy was in creating comprehensive music education programs and training institutions throughout Germany. For young Felix, however, and during the seven years that he studied with Zelter, the older composer remained a dominant musical influence on the younger, providing his pupil with solid musical training rooted in eighteenth-century traditions. Zelter had been a student of Kirnberger, who in turn, had been a student of J.S. Bach. In Mendelssohn’s exercise book from his early period of study with Zelter—before he had reached the age of 9—we find the young musician’s struggle to master the rules of part writing and principles of counterpoint. There is little doubt that the historicist attitude of the mature Mendelssohn, as seen in his efforts to revive the works of Bach and Handel and in his propensity toward strict contrapuntal techniques in his own music, was conditioned by his studies with his beloved teacher.

Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No. 5, Op. 107 “Reformation” (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

Ferdinand David

By a remarkable coincidence, the German violin virtuoso and composer Ferdinand David (1810-1873) was born in the same house in which Felix Mendelssohn had been born a year earlier. David became friends with Mendelssohn after playing a number of chamber music concerts with him. David’s career took him to Estonia and Russia, but in 1835 he answered a call from Mendelssohn, who had just been appointed conductor of the Gewandhaus in Leipzig. David became the Concertmaster, a position he retained for the rest of his life. During the summer of 1838, Mendelssohn wrote to David, “I should like to write a violin concerto for you next winter. One in E minor runs through my head, the beginning of which gives me no peace.” It took Mendelssohn another six years to finish the composition, and he consulted David regularly throughout the composition process regarding violin technique and, ever the perfectionist, continued to make minor adjustments to the concerto. Finally, on 13 March 1845, David, playing his 1742 Guarneri violin, gave the premiere of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. The work was an instant hit and remains a cornerstone of the repertoire today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Felix Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (Chad Hoopes, violin; Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra; Kristjan Järvi, cond.)