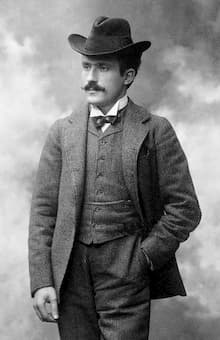

Violinist Samuel Dushkin and Stravinsky © uchukyoku1 / Youtube

Composers are well-known for spending most of their time in solitude, in the quietness of a room, in front of a desk or an instrument. They are often the loners of music. But is composing always a one-person job? Are there any secret collaborators that allow the composer to get his work to full completion? Are there instances when the composer’s block is solved through a nudge? What about unfinished works and posthumous completion of works? Here are some well-kept secrets of the composer’s true allies.

The usual suspects… Copyists whose job is to reproduce several copies of music manuscripts — might they have corrected what they could have perceived as unnoticeable mistakes. Arrangers, who take compositions for a small ensemble — or even piano solo — and arrange it for orchestra, or the other way around — surely their choices influence the final result. Instrumentalists, who allow a composer to write a playable piece for an instrument that they do not play — the story goes that the passport chord, played at the beginning of each movement of Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto took its name after the violinist Samuel Dushkin took off the composer’s doubt in his choice of chord that he had understood as being unplayable; deepening his conviction that he was incapable of writing a concerto for violin. Luckily that was not the case.

Igor Stravinsky: Violin Concerto in D Major – I. Toccata (Itzhak Perlman, violin; Boston Symphony Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Manfred Eicher with Arvo Pärt © The Irish Times

With the rise of the recording industry during the 20th century, producers’ opinions have grown enough to influence the composition of a piece. Manfred Eicher — the founder of the ECM — is certainly responsible for shaping the sound of his record label and therefore the sound of the composers that have released with him; Pärt, Kurtág, Mansurian, Tormis, Kõrvits etc. There is truly a signature sound that comes from the producer collaboration with the composer from the beginning of the creative process.

Arturo Toscanini © Wikipedia

What about when the ideas come from the creative mind of someone else? Clara Schumann — a composer of her own — is famous for having advised her husband’s works, and as her publisher has adapted many of his lieders to the piano.

What about works that never got to be completed by the composer? In fact, there are countless of well-known works that are the result of a two-step process; Mozart’s Requiem was left unfinished at the composer’s death, and completed by the Austrian composer Süssmayr; Puccini’s Turandot owes much of it success and completion thanks to the work of Italian composer and friend of Toscanini, Franco Alfano; and Borodin’s Prince Igor was completed thanks to Rimsky-Korsakov. The later is known to have completed and created alternative works for many composers including Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina — completed by Ravel, Stravinsky and Rimsky-Korsakov all together! Finally, and anecdotally, Holst’s The Planets has been completed in 2000 by Matthews, who added Pluto, discovered in 1930, as the last planet and movement.

While the composer often takes the credit, it is important to recognise how collaborative music is — and to the same extent art. How much would have Michelangelo or Warhol done if it was not for their students, apprentices and collaborators? Success is rarely a one-person thing, and there is nothing such as a self-made artist; at least not in music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter