Let’s continue to look at Debussy’s relationships with his fellow artists and musicians. The Scottish operatic soprano Mary Garden wrote, “I honestly don’t know if Debussy ever loved anybody really. He loved his music – and perhaps himself. I think he was wrapped up in his genius… He was a very, very strange man.” After Debussy left his family for Paris, he spent most of his afternoons and evenings studying and composing at the Vasnier household. Eugène-Henri Vasnier was a Parisian building contractor, architect, and an intellectual with a fine taste for the arts. His wife, Marie-Blanche Vasnier was beautiful, eleven years younger, and a gifted amateur singer. Debussy was employed as an accompanist for her vocal lessons, and she schooled the 18-year-old composer in the art of love.

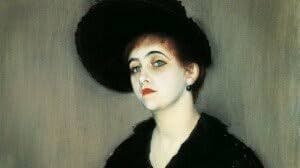

Marie-Blanche Vasnier

Debussy’s 8-year affair with Ms. Vasnier involved a significant maternal element, with Marie-Blanche guiding him into the world of literature. She certainly inspired a substantial number of love songs. Debussy writes in assorted dedications, “To Madame Vasnier, these melodies, conceived in a way by your memory, can only belong to you, as the author belongs to you.”

Claude Debussy: Fêtes galantes I (Suzanne Danco, soprano; Hermann Reutter, piano)

Camille Claudel

The sculptress Camille Claudel (1864-1943), sister of the poet Paul Claudel, started working in the workshop of Auguste Rodin in 1884. She became his inspiration, acted as his model, his confidante, and his lover. An art critic described her as “A revolt against nature: a woman genius,” and her early works in the spirit of Rodin show imagination and lyricism quite her own, particularly in the famous The Waltz of 1893. While we are well informed on her love affair with Rodin, the nature of her relationship with Debussy is still an object of much speculation.

Camille Claudel: La Valse

Robert Godet reports that they were in instant agreement on a number of essential points: “love of Degas, indifference or skepticism towards some of the Impressionists who had become ubiquitous, and admiration for Japanese artists, especially Hokusai.” Debussy kept a copy of The Waltz in his studio until his death, and his piano student Mademoiselle Worms de Romilly asserted that Debussy “always regretted not having worked at painting instead of music.” Ever since his years at the Conservatoire, Debussy felt that he had more to learn from artists than from career-obsessed musicians. “You are getting nowhere,” M. Croche once told him, “because you know nothing but music and obey barbaric laws.” Although it is not known if Debussy and Claudel ever became lovers, when the relationship ended, Debussy wrote: “I weep for the disappearance of the Dream of this Dream.”

Claude Debussy: La mer (London Symphony Orchestra; Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, cond.)

Among Debussy’s friends from his early years at the Conservatoire, only Paul Dukas (1865-1935) was able to maintain a steady, if distant relationship. Throughout, Dukas was sympathetic to the emotional and artistic problems with which Debussy was wrestling. He pointedly describes him as “capable of alienating affections, and therefore capable of cultivating them… Since an artist liberates himself and only himself, music cannot exist independently of the man who writes it… Trusting his instinct infallibly, Debussy baffled people unable to measure the intensity of his instinctive reactions.”

Debussy and Dukas, 1896

Dukas and Debussy were highly supportive of each other as music critics. Debussy wrote in the Revue Blanche in 1901, “Monsieur Paul Dukas knows what music is made of. It is not just brilliant sound designed to beguile the ear until it can stand no more… For him, it is an endless treasure trove of possible forms and souvenirs with which he can cut his ideas to the measure of his imagination. He can hold his emotion in check and shelter it from superfluous declamation; he therefore never stoops to the kind of embroidery that so often spoils the basically beautiful.” Like Debussy’s Pelléas, Dukas based his Ariane et Barbe-Bleu on a Maeterlinck play and also found symbolic and emotional depths in the text which he luminously translated into music.

Claude Debussy: Pelléas et Mélisande (Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerald Finley, bass; Franz-Josef Selig, bass; Bernarda Fink, alto; Joshua Bloom, bass; Elias Mädler, treble; London Symphony Chorus; London Symphony Orchestra; Simon Rattle, cond.)

Debussy entered the Prix de Rome competition for the first time in 1883 and was runner-up to Paul Vidal. When he won the coveted prize the following year, he reluctantly left the musical scene in Paris and his romance with Marie Vasnier behind and departed for Rome. It was a deeply unhappy time for Debussy, however, he found a close friend in Gustave Popelin. He was Debussy’s schoolmate at the Villa Medici, and he had been the winner of the 1882 Prix de Rome in painting.

Gustave Popelin

In his letters to Popelin, Debussy reveals a genuine and sensitive side that he seldom allowed others to see. He openly announced his feelings towards Mme Vasnier, admitting that he was terribly lonesome and easily discouraged by his work. His friendship with Popelin was one of the reasons that Debussy remained at the Villa Medici for the required two years, as he writes, “The intellectual discussions we shared and the advice he gave me greatly influenced my music.”

Claude Debussy: Ouverture Diane (Adrienne Soos, piano; Ivo Haag, piano)

Ernest Chausson was slightly older than Debussy, and he was one of his mentors at the Paris Conservatoire. Chausson became something like a big brother, an admirer, and even a patron to Debussy. They came from very different backgrounds, and when Debussy needed money, Chausson gladly came to his rescue. They became good friends and shared a mutual admiration for each other’s music. And they gave each other plenty of musical advice, with Debussy writing, “One thing I’d like to see you free yourself from is your preoccupation with the inner parts of the texture. By which I mean that too often we’re concerned with the frame before we’ve got the picture; it was our friend Richard Wagner, I think, who got us into this fix.” And when the Société Nationale de Musique performed La Demoiselle Élue, Debussy’s third commission sent from Rome, Chausson was overjoyed.

Chausson turning pages for Debussy

In the summer of 1893, Chausson rented a house in Luzancy, in Seine-et-Marne, and invited Debussy to come for a long stay. Knowing of Debussy’s keen interest in the music of Modest Moussorgsky, Chausson had sent off for a score of Boris Godunov and Debussy spent many hours at the piano playing thru the opera. Chausson was a traditional family man who happily lived with his wife and five children, and he expressed disapproval at Debussy’s promiscuous lifestyle. Their short but intense friendship ended over Debussy’s affair with Thérèse Roger. Unfortunately, they never had the chance to reconcile as Chausson died in a bicycle accident in 1899.

Claude Debussy: La Demoiselle Élue

Claude Debussy was a great admirer of the works of Igor Stravinsky. He claimed, “that Stravinsky played real music…and that he alone had the ability to transform mechanical souls into human beings.” In a letter to Robert Godet, Debussy wrote, “Did you know that quite near you, in Clarens, there’s a young Russian composer. Igor Stravinsky, who has an instinctive genius for color and rhythm? I’m sure you’d like both him and his music… And he’s not all tricks. He writes directly for orchestra, without any intermediate steps, and the outline of his music follows only the promptings of his emotion. There are no precautions or pretentions. It’s childish and savage. Even so, the organization is extremely delicate.”

Photo of Debussy and Stravinsky, 1910,

taken by Erik Satie

The two composers first met in June 1910 after the premiere of The Firebird. They went to dinner, and afterward, Debussy wrote, “It’s not perfect, but, in certain respects, it’s an excellent piece of work nonetheless because the music is not the docile slave of dance. Debussy’s enthusiasm for Stravinsky’s music initially extended to The Rite of Spring, which the two composers played through in a four-hand arrangement. And it is in Khamma, that Debussy’s reaction to Stravinsky’s music is clearly evident, even though Stravinsky unambiguously stated, “that there was no change in Debussy’s style owing to our contact.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Claude Debussy: Khamma (Singapore Symphony Orchestra; Lan Shui, cond.)

There is no reference to Debussy’s daughter, she was very important for the composer, I read..