We’ve looked at Monumental Beethoven where Beethoven is a presence that overwhelms everything – he’s depicted in statuary all over the world. There’s another type of artwork, however, where Beethoven appears, but not front and center. He’s used as a reflection on the action in the painting, either to give the action credence or to cast a question on the proceedings.

We’ll start with Josef Danhauser’s 1840 painting, Franz Liszt Fantasizing at the Piano. It’s a striking romantic work. At the center, Liszt is at an ornate Graf piano, music tossed everywhere, gloves and a handkerchief scattered on the lid. Piles of music are underneath a bust of Beethoven, who stares sightlessly above the head of all those gathered.

Danhauser: Franz Liszt Fantasizing at the Piano (1840) (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Alte Nationalgalerie)

Franz Liszt: Beethoven – Symphony No. 6 in F Major, S464/R128, “Pastoral”: I. Awakening of Cheerful Feelings Upon Arrival in the Country: Allegro ma non troppo (Glenn Gould, piano)

Below Liszt, Marie d’Agoult sits on the floors, leaning with her head on the piano, her hair undone from the tight ringlets or braids that would have framed her face. Her cloak has slipped off her shoulder. Marie d’Agoult, although married to the Count d’Agoult, lived with Franz Liszt from 1835 to 1839, and had 3 children with him: Blandine, Cosima (who married Hans von Bülow and then Richard Wagner), and Daniel, who was a promising pianist when he died age 20.

Lehmann: Marie D’Agoult (1843)

Next, seated, is the French writer George Sand, pointed to some text held in the lap of the French author Alexandre Dumas, père (or Alfred de Musset). Between them, holding his own text is Victor Hugo (or Hector Berlioz), and behind George Sand’s chair is the Italian virtuoso violinist Niccolò Paganini and the opera composer Gioachino Rossini. Rounding out the Italian connection is the wall portrait of Lord Byron. At the back left is a statue of Joan of Arc.

The painting was commissioned by Conrad Graf (1782-1851), maker of the finest pianos of his day, and, unfortunately, was created solely out of the painter’s imagination. Graf pianos were used by Beethoven, Chopin, and Robert and Clara Schumann, and even the young Mahler. Liszt, on the other hand, was infamous for destroying Graf pianos during his concerts and in one concert in Vienna in 1838, Liszt destroyed 2 Graf pianos and one Erard piano due to the violence of his playing.

If we move forward and to the east, we have a painting by the last Caliph of the Ottoman Dynasty, Abdulmejid II (1868-1944). As a painter, he is considered one of the most important in the late Ottoman period. Many of his paintings show the influence of Western Europe on Islamic countries.

The 1915 painting Beethoven in Harem (or Palace Beethoven) depicts Abdulmejid at the right listening to his first wife, Şehsuvar Kadınefendi, playing violin, Hatice playing piano and his son, Ömer Faruk, playing cello. The two women leaning over the chairs include his third wife Mehisti Hanım, who had entered the royal harem as a child, given by her father. Mehisti married Abdulmejid in 1912. The setting is the summer palace at Bağlarbaşı.

Abdulmejid II: Beethoven in Harem (1915) (Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture Collection)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio No. 4 in B-Flat Major, Op. 11, “Gassenhauer” (version for violin, cello and piano) (Gil Shaham, violin; Anne Gastinel, cello; Nicholas Angelich, piano)

Abdulmejid was also a pianist, Mehisti Hanim’s sisters Şehsuvar and Hayrünnisa played the violin and Mehisti played cello for ensemble performances at the palace, played for family.

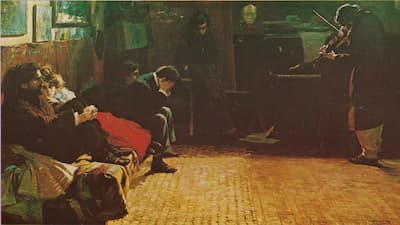

The Italian painter Lionello Balestrieri (1872-1958) showed the other side of Beethoven workshop. In his 1900 painting Beethoven (Kreutzer Sonata), he depicted an evening of music in which he often participated. In a dimly lit garret in Paris, the violinist Giuseppe Vannicola (1876-1915) plays Beethoven. However, in this depiction of his friend and flat-mate Vannicola, he’s not showing the violinist’s love for Beethoven but how he tried to use Beethoven to advance his own career.

Balestrieri: Beethoven (Kreutzer Sonata) (1900) (Trieste: Revoltella Museum)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47, “Kreutzer” – I. Adagio sostenuto – Presto (Yehudi Menuhin, piano; Hephzibah Menuhin, piano)

Vannicolo was inspired by the story of the English violinist G. A. Bridgetower who gave the first performance of the Kreutzer Sonata, reading over Beethoven’s shoulder as he played at the piano. Bridgetower made a change in the second movement that Beethoven commented on and accepted, making it part of the final score. Beethoven dedicated the score to Bridgetower but changed the dedication to Rudolphe Kreutzer when he fell out with Bridgetower. Vannicolo sought to make his own mark on the Beethoven world through his own inspired performances. On the left we see the effect of his playing on his friends as they endure his impromptu concert: they look miserable and one holds his head in his hands (note his thumb covers his ear). On the back wall is the death mask of Beethoven, untouched by either the performance or the performer.

A final painting is by the English artist Alfred Edward Emslie (1848-1918). His 1912 work A sonata of Beethoven shows a young woman in the foreground playing a small piano. In the background a familiar figure sits in a window and writes on a pad on his knee.

This painting follows a trend in European painting of depicting ‘unseeable’ subjects and we should note that the two people are dressed in clothes of different time periods. Is it Beethoven or just the idea of Beethoven? We only have his name through the title of the painting and perhaps it’s more of a reminder of how much music has Beethoven in the background.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter