“Great art presupposes the alert mind of the educated listener”

I am sure that at one point or another you’ve heard the slant that Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) is the only classical composer who uniquely can empty any concert hall by the mere mentioning of his name on the programme. It is indeed a rather cheeky overstatement that somehow blames Schoenberg for divorcing music from music lovers.

Arnold Schoenberg

Fact is, however, that Schoenberg is probably the first great composer in modern history whose music has not entered the repertoire almost a century and a half after his death on 13 July 1951. Schoenberg was a polymath, a fantastically talented individual of substantial complexity, who lived, worked and engaged with one of the most tumultuous political and artistic periods in human history.

We primarily know Schoenberg as a serious composer of modern music, whose experimentations with atonality led to the development of the dodecaphonic, better known as the twelve-tone method of composition. However, Schoenberg was also a painter of considerable ability who exhibited alongside Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky. He was also a charismatic teacher and brilliant theorist who authored a substantial number of books and essays.

Arnold Schoenberg: Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4 (Chamber Orchestra)

Late Romantic Musings

Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schönberg, he changed to the anglicised form Schoenberg when he left Germany and re-converted to Judaism in 1933, was born into a lower middle-class Jewish family in Vienna. His mother Pauline, a native of Prague, was a piano teacher, and his father Samuel, a native of Hungary, a shopkeeper. Although he took counterpoint lessons with the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, Schoenberg was essentially self-taught.

Schoenberg composed a considerable quantity of music during his childhood, but as he later explained, “all my composition up to about my seventeenth year were nothing more than imitations of such music as I could become acquainted with.” However, he did start to probe the future direction of Germany music, addressing the legacies of Brahms and Wagner.

Arnold Schoenberg: String Quartet No. 1 in D minor, Op. 7

Blending Brahms and Wagner

Arnold Schoenberg

Beginning with songs and string quartets written around the turn of the century, Schoenberg presented works that simultaneously contained characteristics of both Brahms and Wagner. On one hand we find a clarity of tonal and motific organisation typical of Brahms, with “balanced phrases and an undisturbed hierarchy of key relationships.” Concordantly, he explored bold incidental chromaticism, aspiring to a Wagnerian representational approach to motivic identity.

By combining Brahms’ approach to motivic development and tonal cohesion with Wagnerian narrative of motific ideas, Schoenberg was recognised by both Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler as a significant composer. Strauss would eventually turn away from Schoenberg, but Mahler adopted Schoenberg as a protégé. Despite his Jewish background, Schoenberg converted to Lutheranism in 1898. “At no point in my life,” he later wrote, “have I been unreligious, let alone anti-religious.” Schoenberg returned to the faith in which he had been brought up in 1933.

Arnold Schoenberg: Erwartung, Op. 17

Atonality

Schoenberg married Mathilde Zemlinsky in 1901. The couple initially moved to Berlin, where Schoenberg was active on the cabaret scene. Thanks to the influence of Richard Strauss, Schoenberg returned to Vienna and became a private teacher of composition and theory. In 1904, he was joined by two new recruits, Anton Webern and Alban Berg.

Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde had far-reaching effects regarding the emancipation of dissonance, as tonal centres and traditional dissonance-consonance relationships became subservient to dramatic expression. Starting around 1908, Schoenberg’s music began to experiment with a variety of ways to address the absence of traditional keys and tonal centres. His first explicitly atonal piece is identified as the second string quartet, Op. 10, with soprano.

Arnold Schoenberg: Chamber Symphony No. 1, Op. 9

Expressionism

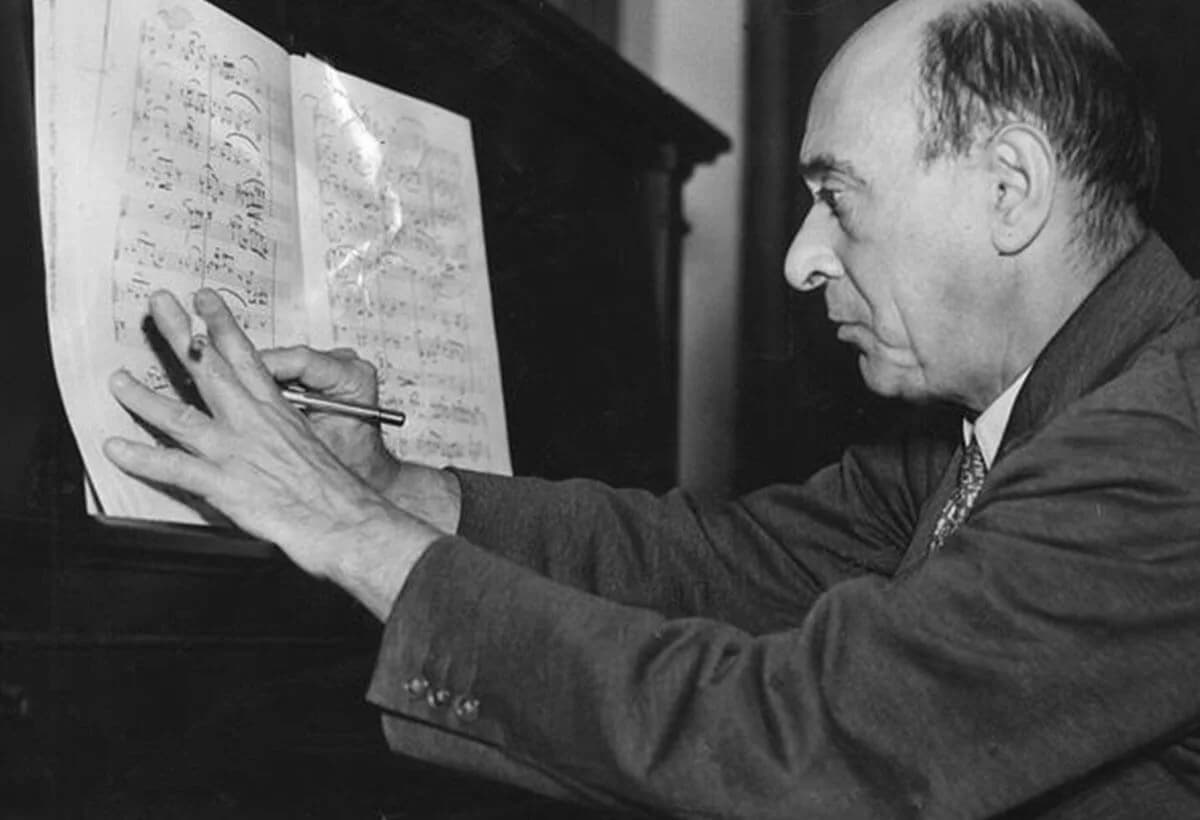

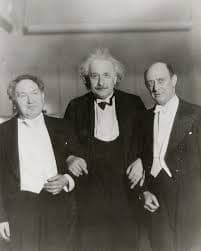

Godowski, Einstein and Schoenberg

The disintegration of functional harmony seemingly destroyed the conditions for large-scale forms. However, as a scholar wrote, “dissonance’s new independence permitted, at least in an orchestral context, unprecedented simultaneous contrasts. It is not. Only novelty of expression but the power to bring seemingly irreconcilable elements into a relation that gives the music its visionary quality.” For a period of time, Schoenberg strongly believed that the dictates of expression would be able to renounce motivic features as well as tonality.

However, the way forward was the construction of larger forms on the basis of text. And the texts largely drew on a modernist movement called Expressionism, a poetic style that presented the world from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas. The half-hour monodrama Erwartung features a single female character, full of fear and apprehension, as she wanders through a forest at night in search of her lover. The only dramatic event is her discovery of his murdered body, followed by her monologue recollecting their love, jealousy and “a sense of reconciliation born from exhaustion.”

Arnold Schoenberg: Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 (Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

World War I

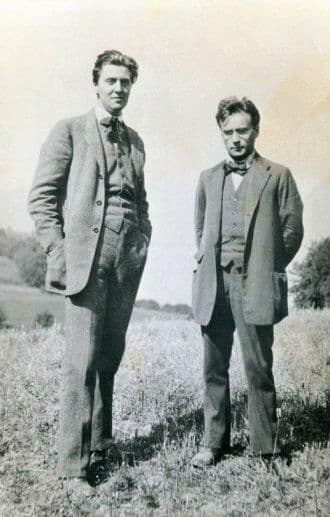

Alban Berg and Anton Webern

Arnold Schoenberg was 42 when he was called up to the army. He was medically examined in 1915 and rejected, but a second medical examination reversed the decision. With many of his students called up as well, his teaching ceased completely. In addition, he was not able to work uninterrupted or for longer periods of time, and as a result, he left many unfinished works and undeveloped beginnings.

One thing is for sure: WWI sped up the deteriorating relationship between contemporary composers and the public. As such, Schoenberg founded the “Society for Private Musical Performances.” The press was excluded and details of programmes not available in advance. Within the period from February 1919 to the end of 1921, 353 performances of 154 works were given in 117 concerts. Once Schoenberg was made president of the International Mahler League, he organised festivals of his own works and gave a series of lectures on music theory. This was the time of the formulation of serialism.

Arnold Schoenberg: Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23

Serialism

After the war, Schoenberg was looking for a musical order that would make his musical texture simpler and clearer. The result was a method of composing with twelve tones which are related only with and to one another. All twelve pitches of the chromatic scale within the octave are regarded as equal, and no one note is given emphasis. For Schoenberg, it was not merely a compositional method but an attempt for music to regain a genuine and valid simplicity of expression, such as in the music of his beloved Mozart and Schubert. Musical language had to be renewed.

Serialism, as a method of composition, does not give any indication of musical style. For Schoenberg, this meant a return to Classical forms “in his need to find new scope for the inherently developmental cast of thought.” Schoenberg considered 12-tone composition, later retitled Serialism akin to the discoveries of Albert Einstein in the field of Physics. As he related to a friend, “I have made today a discovery which will ensure the supremacy of German music for the next hundred years.”

Arnold Schoenberg: Suite, Op. 29 “Gigue”

Exile and Legacy

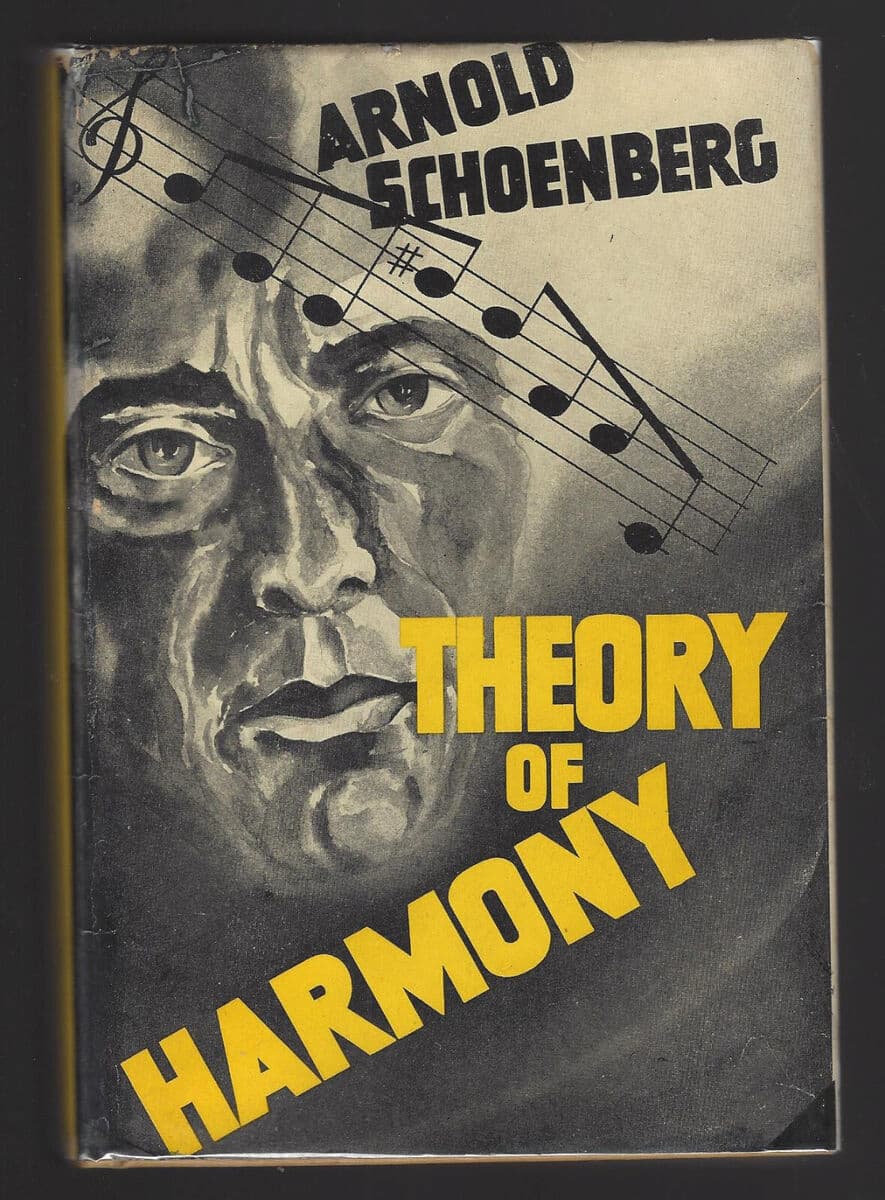

Schoenberg’s Theory of Harmony

Between 1920 and 1936, Schoenberg wrote a series of marvellous instrumental works of striking individuality. He serves as Director of a Master Class in Composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, but growing Anti-Semitism and the government’s intention to remove Jewish elements from the academy hastened his departure for Paris. Searching for employment, Schoenberg accepted an appointment in Boston in the autumn of 1933. Struggling with health issues, Schoenberg moved to Los Angeles and eventually became a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Schoenberg enjoyed little peace of mind as he found the alien surroundings hard to accept. Few of his students were able to fully benefit from his knowledge and experience, and his relatives and friends in Europe were under constant threat. Schoenberg continued to compose works, nearly all religious in inspiration, and he revised his vast collection of unpublished essays and articles under the title Style and Idea. His opera Moses and Aron remained unfinished.

Schoenberg’s twelve-tone works and the truly revolutionary nature of this new system became “one of the most central and polemic issues among American and European musicians during the mid-to late-twentieth century.” Various ideologies are still hotly debated, and music lovers continue to find difficulty with Schoenberg’s music. Attempts to popularise the music of Schoenberg, despite roughly forty years of advocacy and countless “books devoted to the explanation of this difficult repertory to non-specialist audiences,” have undoubtedly failed. Be that as it may, Schoenberg saw all great music as “expressing the longing of the soul for God, and genius as representing man’s spiritual future.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter