Many composers and listeners have a twisted fascination with dark themes like sin, death, punishment, and hell.

Today, we’re looking at ten pieces of classical music about hell and seeing how classical composers have crafted vivid musical depictions of the underworld.

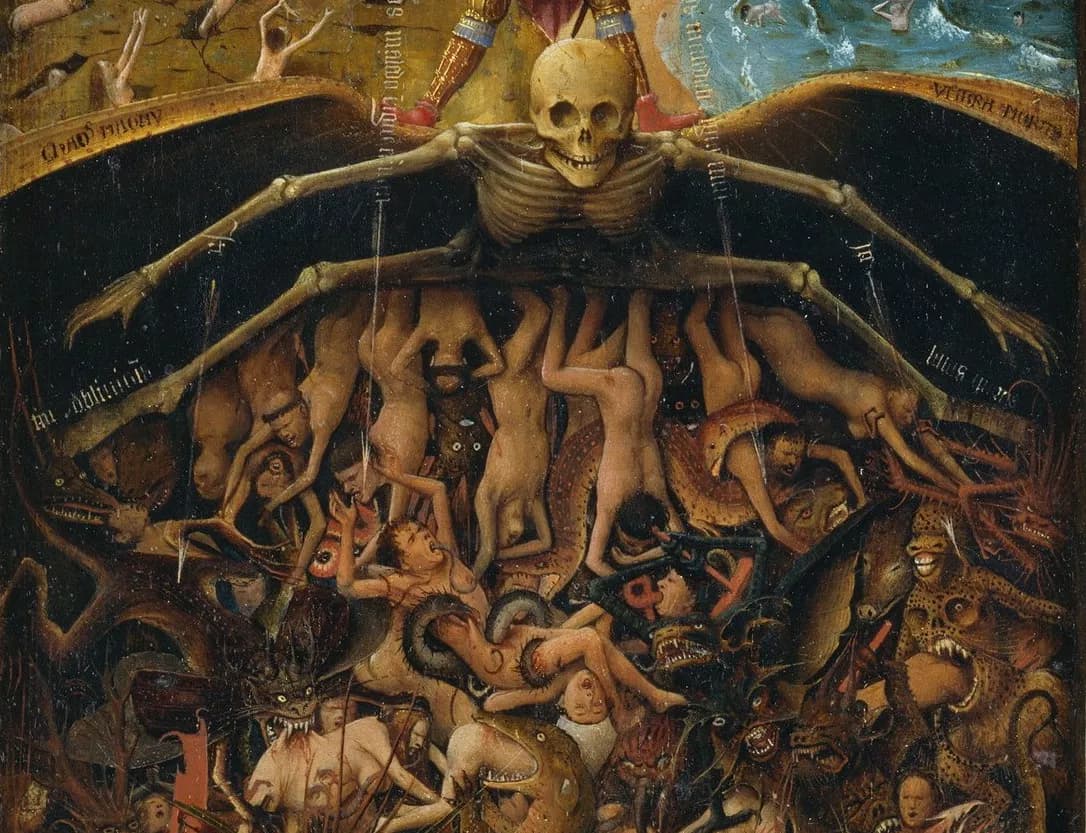

Detail view of Jan Van Eyck, The Last Judgment, ca. 1440–1441 © Wikimedia Commons

Let’s begin our musical journey to hell and back.

Commendatore Scene from Don Giovanni by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1787)

Don Giovanni’s eponymous main character is a hellish nightmare of a human being. He uses his wealth, power, and good looks to hurt and seduce women. (According to one aria, his little black book features over two thousand names.)

Don Giovanni meets Il Commendatore (Met Opera)

The opera opens with Don Giovanni trying to assault the Commendatore’s daughter. The Commendatore challenges him to a duel to avenge his daughter, but Don Giovanni kills him.

Toward the end of the opera, in a truly chilling moment, a statue of the Commendatore knocks on a door and invites Don Giovanni to repent of his sins. Don Giovanni refuses, and he is dragged down into hell.

Fahrt zum Hades by Franz Schubert (1817)

Mozart’s Commendatore Scene was written in D-minor, and Schubert stuck with that key when penning his song Fahrt zum Hades (“Journey to Hades”).

The lyrics were written by his dear friend, depressive poet Johann Mayrhofer, who he had met in 1814. Together, the two friends depict the narrator’s journey to the underworld.

Schwind: Johann Mayrhofer

The boat moans, the cypresses whisper;

hark, the spirits add their gruesome cries…

Pandemonium from La Damnation de Faust by Hector Berlioz (1845)

Composer Hector Berlioz wrote La Damnation de Faust, inspired by Goethe’s poem Faust, in 1845.

He bestowed the grandiose term “dramatic legend” on the work, seeing as it was neither an opera nor an oratorio.

The forces required to perform the Damnation include four vocal soloists, an adult chorus, a children’s chorus, and full orchestra.

At the end of the work, the main character, Faust, seduces an innocent woman. Later, his companion Méphistophélès – the devil in gentleman form – offers to bring him to the woman, and Faust agrees.

But on the way, Faust realizes that Méphistophélès has lied to him: he is bringing Faust straight into hell, where he will face eternal torment.

Dante Symphony by Franz Liszt (1856)

Liszt’s Dante Symphony was, like Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust, inspired by a poem: in this case, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

Domenico di Michelino: Dante, 1465 (Florence Cathedral)

In the Divine Comedy, Dante himself is guided by the unlikely trio of Virgil (to represent human reason), Beatrice (a woman Dante only met twice but had an unrequited passion for), and Saint Bernard of Clairvaux.

Over the course of the poem, Dante and his guides visit hell, purgatory, and heaven.

Liszt traces their journey in his Dante Symphony. Accordingly, the opening begins with a terrifying portrait of hell.

Interestingly, at the same time he was writing the Dante Symphony, Liszt was writing his own musical interpretation of Faust. The similar ideas behind both works make them natural companions.

Dies Irae from Requiem by Giuseppe Verdi (1873)

Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem is unique in that it’s too operatic to be used effectively in a liturgical setting, but also too overtly religious to be staged as an opera. Today it is most often presented in a concert setting.

You can hear for yourself why the requiem wouldn’t work within the confines of a traditional Catholic Requiem Mass while listening to the Dies Irae (Day of Wrath).

This music is wild-eyed and massive: some of the most aggressive of the entire nineteenth century.

Verdi’s Dies Irae depicts God’s judgment of the people of the world. Brass instruments summon souls to His throne to be judged. The sinful will be discarded into eternal flames, while the saved will ascend into paradise.

Francesca da Rimini by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1876)

Francesca da Rimini was a real-life woman who appeared as a character in Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Francesca da Rimini

Around 1275, Francesca entered into an arranged marriage with a lame nobleman for political purposes. Unfortunately, she ended up falling in love with her husband’s brother.

The two hid the affair for a decade, but around 1285, they were caught in bed together by her husband, who killed them both.

Francesca and her lover appear in Dante’s Divine Comedy as residents of the second circle of hell, reserved for the lustful. They are buffeted by constant winds that simulate how they were buffeted by their passion for one another.

Tchaikovsky approached the tragic story with all of his customary dramatic flair.

Dante by Enrique Granados (1895-1910)

Francesca’s story is also chronicled in Dante by composer Enrique Granados.

This half-hour symphonic poem features two parts, both based on the Divine Comedy: first, Dante’s descent into hell, and secondly, the story of Francesca.

After a somber two-and-a-half-minute introduction, the music turns lush and tragic. There are unmistakable hints of Wagner, Richard Strauss, and other late Romantic composers here.

The Book of the Seven Seals by Franz Schmidt (1937)

This two-hour oratorio for chorus, vocal soloists, organ, and orchestra is overwhelming.

It is inspired by the Book of Revelation, the mysterious final book of the Bible. In Revelation, there is a book with seven seals. Nobody has been deemed worthy enough to open the seals until the arrival of the Lamb of God: a symbol of Jesus Christ and his sacrifice that atones for mankind’s sins.

As the oratorio goes on, the seals are broken one-by-one. A variety of disasters ensue.

Once the seventh seal is opened, a dragon – symbolizing Satan – is bound by angels and cast into hell.

Ave Satani by Jerry Goldsmith (1976)

“Ave Satani” translates into “Hail Satan.” Composer Jerry Goldsmith used the phrase in 1976, when he was writing a choral piece for the classic horror film The Omen.

Film poster for The Omen. Copyright 2002, © 20th Century Fox

In The Omen, an American diplomat named Robert and his wife Kathy have a baby who dies. Robert, without telling his wife, adopts another child named Damien whose mother has died in childbirth, pretending it’s their biological child.

Five years pass, then strange, violent, terrible things start happening to the little family. Turns out Damien is the Antichrist, and child and parents are forced into a supernatural battle with one another.

In Ave Satani, Goldsmith employs chilling (if at times inaccurate) Latin. Translated and corrected, the words read:

We drink the blood

We eat the body

Raise the body of Satan

Hail, Hail Antichrist!

Hail Satan!

Etude No. 13, The Devil’s Staircase, by György Ligeti (1988-1994)

The Devil’s Staircase comes from the second book of Ligeti’s etudes for solo piano. It seems to depict a being – maybe Satan himself; maybe not – ascending a staircase, traveling through hell.

To portray the long-winded climb, Ligeti eschews most barlines, resulting in dizzying phrases that travel ever-upward.

Keep an ear out for that ascending musical line, as well as the ominous chords in the base that signify when the climber has apparently, finally, run out of stairs to climb.

At this point, has Satan been let loose into our world, or did a condemned soul somehow escape? Or has this entire piece been representing something less literal, such as the Cantor function in mathematics, which is also known as the devil’s staircase? It’s up to your imagination to decide.

Conclusion

From Franz Schubert’s gentle song about arriving in the underworld to Franz Schmidt’s terrifying depiction of the seven seals being opened, we hope you’ve enjoyed this little tour of classical music about hell!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter