Ludwig van Beethoven was born in 1770 in Bonn, Germany. He would become one of the most important figures in the history of Western music.

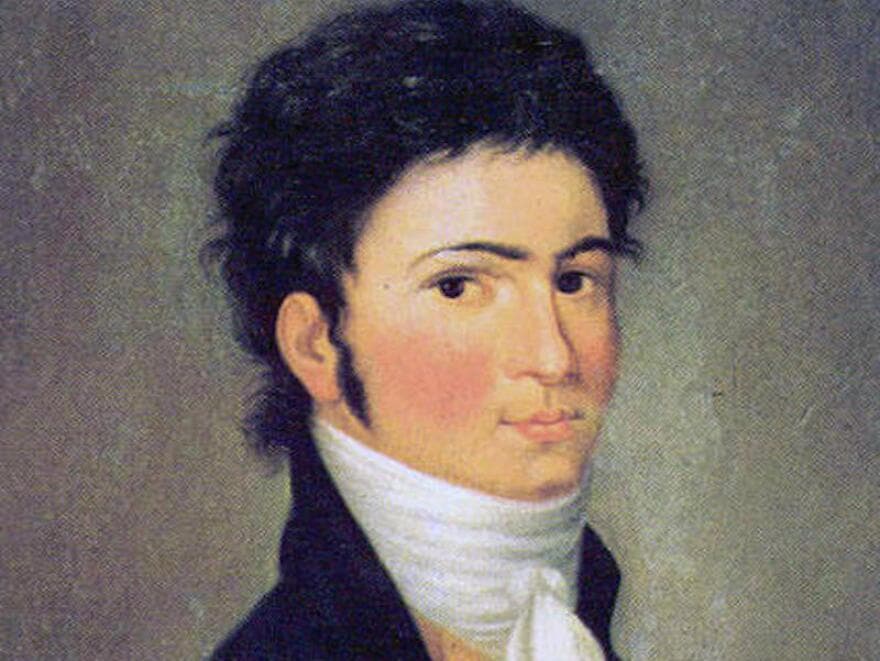

Beethoven in 1801

Here are some things you should know about him:

He always had a troubled home life.

His father was abusive and alcoholic, and he forced Ludwig to practice piano as a child.

Later in life, Beethoven never found a wife, a state of affairs that upset him deeply for a long time. (He did have a string of largely unrequited love affairs with unavailable noblewomen, though.)

After his brother’s death, he fought for custody of his nephew Karl, who developed mental health issues of his own. That dysfunctional relationship that caused more pain than joy.

In the end, he was a man constantly searching for healthy family connections, and he never really found them.

The great central struggle of his life was the long, agonizing process of going deaf.

This painful process began around 1798, when Beethoven was in his late twenties.

In 1802 he wrote a famous unsent letter that was rediscovered after his death, known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, in which he confessed that he had contemplated suicide but decided to keep living for his art.

Beethoven was born into a politically and artistically tumultuous time.

The French Revolution began when he was a boy, and its repercussions echoed across Europe throughout his lifetime.

He had a love/hate relationship with Napoleon and all that he came to represent. Those political feelings found their way into many of Beethoven’s works.

Beethoven was the first major composer to make his living outside of a powerful institution.

Bach and Mozart, for example, were church or court musicians. Beethoven, however, was a freelance composer and virtuoso pianist.

Every composer who has come after Beethoven has been intimidated by the sheer force of his creative personality.

Like it or not, there was a time before Beethoven and a time after Beethoven.

What works might sum up the creative life of such a musical giant? Let’s take a look.

Piano Trio #1, Op. 1 – 1795

Let’s start off with some of Beethoven’s earliest published pieces, a set of three piano trios published in 1795, the year he turned 25 years old.

Piano trios are pieces written for piano, violin, and cello. Beethoven often saved his most intimate, personal music for these kinds of small, intimate ensembles.

These works are charming early Beethoven. Knowing them helps a listener better appreciate his later artistic evolution – and revolution.

Piano Sonata No. 8 (Pathétique) – 1798

Beethoven matured rapidly. In this sonata, you can see how by 1798 he embraced expressivity with a new intensity. It’s no coincidence that this evolution quickened after he began experiencing the physical and emotional agony of encroaching deafness.

The first movement of this sonata is dramatic, sounding like an opera for piano alone. The second movement is famous for its noble pathos. The last movement is restless and buzzing.

The sonata is full of fleet fingerwork; wistful, tragic melodies; and sudden loud jolts, a Beethoven trademark that always heightens the drama.

Violin Sonata No. 5 (Spring) – ca. 1800

Even though Beethoven was processing intense feelings related to his health issues, he was still capable of writing incredibly elegant, sophisticated music. His fifth violin sonata is a case in point. It’s so fresh and cheerful that it earned the nickname “Spring Sonata” after his death.

That said, notice how often brief shadows threaten to turn the work tragic before returning to gentility, or how various notes are accented in particularly sharp or startling ways.

Even in Beethoven’s most graceful music, a dangerous intensity always seems to be lurking just beneath the surface.

Piano Sonata No. 14 (Moonlight) – 1801-02

Everyone knows and loves the Moonlight Sonata!

But here’s some trivia for you… This piece wasn’t originally called the Moonlight Sonata. It only got that nickname from a critic decades after Beethoven’s death.

This happened countless times with Beethoven’s output, where some Romantic era writer would nickname a Beethoven work, and the nickname would stick. As a result, one of the most interesting parts of being a Beethoven listener today is trying to separate the music from the myth.

The Moonlight Sonata is a prime example of that. You’re free to imagine moonlight flickering on a lake, of course. Many listeners before you have! But also let the music speak to you fresh, and see what other mental images or stories come to mind.

Triple Concerto – 1803

Remember how the first piece on this list was written for piano, violin, and cello?

Just eight years after that first trio, Beethoven took the format and wrote another piece for piano, violin, and cello…plus full orchestra. The result is this triple concerto.

This combination was extremely unusual in Beethoven’s time, and it remains very unusual even to this day.

As you can imagine, it’s a challenge to balance all of the instruments effectively, which is one reason why this piece isn’t heard very often today.

But it stands as proud evidence of Beethoven’s passion for experimentation, growth, and innovation.

Symphony No. 5 – 1804-08

Over the course of his career, Beethoven wrote nine extraordinary symphonies.

Symphonies are four-movement orchestra works that follow a specific structure. The genre has a long and storied history stretching back several generations before Beethoven. Symphonies came to be known as the genre in which a composer could really test his or her musical mettle.

Beethoven’s fifth symphony – with its immediately recognizable four-note short, short, short, long opening – was premiered in 1808 in Vienna. (It was first played in a concert that lasted for over four hours in an auditorium that was not heated.)

The drama and jumpiness of the work reflected the time in which it was written. The Napoleonic Wars were in full swing, and everyone was well-aware that the aristocracy’s power was no longer assured. Everyone could feel the old order of things melting away, and the seductive tug of the tenets of Romanticism.

This symphony spoke to the zeitgeist of the era, and has continued to speak to generations since.

Piano Concerto No. 5 (Emperor) – 1809

Beethoven was, at heart, a pianist. The piano remained close to his heart even after deafness made playing it accurately difficult.

In this work you can really hear Beethoven’s “heroic” style coming into focus. It’s grandiose, sincere, optimistic, and maybe even a bit bombastic. Many of Beethoven’s works during this period could be described using those words.

We don’t know why or how the concerto ended up with the nickname of “Emperor.” (It’s just another example of the myths surrounding Beethoven getting tangled up with the music!)

But Beethoven probably wouldn’t have been a fan of the nickname: although he was initially excited about the reforms that Napoleon’s ascent appeared to promise, he was deeply disillusioned by Napoleon’s decision to crown himself Emperor in 1804.

In Beethoven’s mind, in the absence of true democratic leadership, artists needed to be on the front lines of idealism and innovation.

While you’re here, be sure to listen to the second movement. Its hymnlike soulfulness is one of the most sheerly beautiful things Beethoven ever wrote. It starts at 20:45 in the video above.

Egmont Overture – 1809-1810

One of the ways that musicians and artists made political commentary during this time was by reaching into history for inspiration, and letting listeners draw their own parallels between history and contemporary events.

Writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe played this game in 1787, when he wrote a play named Egmont about Lamoral, Count of Egmont. The Count of Egmont was a real-life figure who lived in the sixteenth century. His death at the hands of occupying Spanish forces ultimately helped lead to the independence of the Netherlands.

In 1809 and 1810, Beethoven also played the same game. He wrote music to accompany Goethe’s play: a not-so-subtle statement about life in Vienna during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1809, Napoleon actually quartered himself in the Schönbrunn Palace…and ordered operas to be performed during his occupation! He also experienced his first major military defeat outside of Vienna that same year.

This thrilling portrait of political danger, occupation, and tyranny resonated far beyond Beethoven’s time. In 1956, it became an anthem of hope during the Hungarian revolution. It was not the only time that Beethoven’s music would be used for political purposes.

Für Elise – 1810

This is possibly Beethoven’s most famous work for piano, but, ironically, it wasn’t published until forty years after Beethoven’s death.

The title “Für Elise” translates to “For Elise”, but historians are split as to who the intended recipient was, or even if the name was transcribed from the manuscript correctly before publication. Some options that have been floated over the years include:

- Therese Malfatti, a Beethoven student twenty-two years his junior who supposedly turned down his marriage proposal to marry a nobleman

- Elisabeth Röckel, a soprano twenty-three years Beethoven’s junior who ended up marrying his colleague, composer Johann Nepokmuk Hummel, in 1813

- Elise Barensfeld, a soprano twenty-six years Beethoven’s junior who knew Beethoven.

The bottom line is, we don’t know for sure, but this enchanting little piano piece does remind us how Beethoven never found a woman who wanted to marry him. He was consistently attracted to unavailable or much younger or wealthier women.

That recurring feeling of disappointment and romantic hopelessness impacted his life, career, and art.

Archduke Piano Trio – 1810-11

Beethoven may not have held an official court position, but he did rely on the patronage of wealthy supporters to make ends meet. In the process, he often befriended them or taught them or dedicated work to them. (Sometimes he did all three.)

The “Archduke” piano trio is an example of that kind of relationship. It was dedicated to Archduke Rudolf of Austria, the youngest of twelve children of Emperor Leopold II, who had no hope of ever becoming heir to the throne, but who still wielded financial and cultural power. Beethoven gave the archduke piano lessons. In turn, the archduke supported him monetarily.

It’s fascinating to hear how much more complex this piano trio is compared to the first one on this list. There is so much more contrast compared to the earlier effort.

Piano Sonata No. 29 (Hammerklavier) – 1817-18

This is another work that was dedicated to Archduke Rudolf. Although seven years separate the two works, Beethoven didn’t write much in between.

During that time, Beethoven was suffering from ill health, issues with alcohol, and was drained by a nasty court battle, desperately trying to get custody of his nephew and drag his sister-in-law through the mud.

It’s important when listening to works by classical composers to remember that they were only human, and that they went through stressful times, just like we do.

When Beethoven turned back to composition after this fallow period, his advanced deafness granted him a new creative fearlessness. During this time, he leaned into everything that made him famous: his experimentation, his accented notes and extreme dynamics, his imaginativeness, his artistic conviction.

All of those qualities are on display in his twenty-ninth piano sonata, which was nicknamed the Hammerklavier (Hammer Keyboard).

Symphony No. 9 – 1823-24

The final symphony that Beethoven wrote was his ninth symphony. It was premiered in Vienna in May 1824.

Despite his now total deafness, Beethoven conducted it. He hadn’t been onstage for twelve years, and the performance received a lot of buzz.

What the audience heard was extraordinary: a massive symphony starring not just an orchestra of instrumentalists, but an entire chorus and vocal soloists.

Despite the musicians having to ignore Beethoven’s erratic conducting, the premiere was a great success. After it was finished, one of the soprano soloists gently took him by the shoulders and turned him around so that he could see the applause.

You know part of this symphony, even if you think you don’t: the last movement includes the melody that has come to be known as the Ode to Joy.

It’s so tempting to imagine what might have come after the Ninth Symphony, because it really does feel like a magnum opus. The gauntlet had been thrown for future composers. The symphony would never be the same again.

Grosse Fuge – 1826

Through the 1820s, Beethoven’s health continued to deteriorate. At the end of his life, he returned to how he had begun his career: writing chamber music for small ensembles.

He felt freer than ever to experiment, and experiment he did with his fifteen-minute-long Grosse Fuge (or Grand Fugue).

Beethoven had always been able to hear the music in his head, so he knew intellectually what this music would sound like, even though he couldn’t hear it with his ears. But this fugue was so violent and so dissonant that many people who heard it felt that Beethoven was going mad.

This movement was ignored for generations after Beethoven’s death before finally starting to enter the repertoire in the 1920s, a full century later!

Composer Igor Stravinsky observed that the Fugue is “an absolutely contemporary piece of music that will be contemporary forever.” He ranked it among Beethoven’s greatest achievements.

The late acceptance of the fugue helped to solidify the idea of Beethoven as a visionary Romantic era artist who was ahead of his time.

Conclusion

Beethoven died soon after the fugue was written, in March 1827, at the age of fifty-seven.

His music is extraordinary on its own. But it’s even more extraordinary when put into context. He was a constantly evolving composer who was often lonely and wrestling with debilitating health issues, writing music for a rapidly changing world that wasn’t always ready to fully embrace his innovations.

Beethoven’s output is so large that there is always more to hear. So if one of these works has grabbed you, be sure to keep listening. There’s lots more where these came from!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Missing is one of the deepest, most profound works of art ever gifted to the human race. Beethoven’s “Holy Prayer of Thanksgiving…” movement (partially composed in the Lydian mode) from the late a minor string quartet