“I simply follow my own feelings”

Francis Poulenc

Among the most original and sincere voices of the 20th century, Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) was no revolutionary as his music and personality simply mirror the often-conflicting nature of humanity. Simultaneously earthy and refined, an uninhibited homosexual who fathered a daughter late in his life, Poulenc was a modern urbane composer who was unafraid to indulge his urges for nostalgia and for mystic spirituality.

One of the most eclectic composers who ever lived, “Poulenc borrowed disguisedly from a kaleidoscope of musical languages, speaking clearly, directly and humanely to every generation.” His close friend Darius Milhaud suggested, “Poulenc is music himself; I do not know of any other more direct music, expressed in a simpler way that goes straighter to the target.”

Francis Poulenc: Trois mouvements perpétuels

A Comfortable Start

Francis Poulenc was born on 7 January 1899 in Paris into a wealthy bourgeois family. His father Émile Poulenc was director of a family pharmaceutical business, which eventually became the pharmaceutical giant “Rhône-Poulenc.” His mother Jenny, née Royer, came from a long line of Parisian artists and craftsmen.

Francis Poulenc as a kid, 1903

While his father was a deeply religious Catholic with musical interests primarily focused on Beethoven, his mother was an able pianist who idolized Mozart, Schubert, and Chopin, or what Poulenc later called “a lifelong taste for adorable bad music.” To be sure, the two sources of parental inspiration decidedly shaped Poulenc’s musical personality. As the musicologist Claude Rostand remarked, “In Poulenc, there is something of a monk and something of a rascal.”

First Instructions

Francis started piano lessons at the age of five, and he quickly became fascinated by the music of Debussy, Schubert, and Stravinsky. Poulenc completed a conventional classical education, but the death of his parents and the onset of World War I upset his plans to attend the Conservatoire.

Through his childhood friend Raymonde Linossier, Poulenc was introduced to Adrienne Monnier’s bookshop in the rue de l’Odéon. It was the famed meeting place for the avant-garde poets Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Paul Éluard, and Louis Aragon, and Poulenc eventually set many of their poems to music.

Francis Poulenc: Tel jour, telle nuit, FP 86 (Barbara Hendricks, soprano; Love Derwinger, piano)

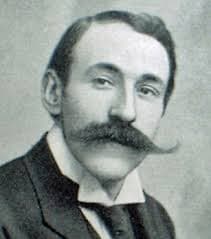

Ricardo Viñes

Ricardo Viñes

The exceptional Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes, who performed premieres of works by Ravel, Debussy, Satie, and Falla, became a pivotal individual in Poulenc’s personal and musical development. In fact, Viñes became his spiritual mentor and Poulenc writes, “he was a most delightful man, and I admired him madly, because in 1914 he was the only virtuoso who played Debussy and Ravel.”

Poulenc later recalled, “I owe Viñes everything. In reality, it is to him that I owe my fledgling efforts in music and everything I know about the piano.” Poulenc had been composing since 1914, but he made his public debut in 1917 with his Rapsodie nègre at an avant-garde concert organized by Jane Bathori. Stravinsky helped him to get the work published, and Poulenc made the acquaintance of Milhaud, Auric, Honegger, Tailleferre and Durey.

Francis Poulenc: Rapsodie nègre, Op. 1

Les Six

Among “Les Six,” a loose grouping of six composers who took their musical bearings from the music hall, the cabaret, and the circus, nobody sensed the age of Toulouse-Lautrec more innately than Poulenc. “I’ve often been reproached about my street music side,” Poulenc once wrote. “Its genuineness has been suspected, and yet there’s nothing more genuine in me. From childhood onward, I’ve associated café tunes with the Couperin Suites in a common love without distinguishing between them.”

Jacques-Émile Blanche: Les groupe de six, 1922 (Rouen: Musée des beaux-arts)

Poulenc’s attempt to study at the Paris Conservatoire was rejected, and throughout his life, the composer was conscious of his lack of academic musical training. It was Ravel who advised him to take composition lessons, and Milhaud introduced him to the composer and teacher Charles Koechlin. Lessons continued for about four years, and Poulenc gradually developed the deliciously bohemian flavour of his music.

Francis Poulenc: Les mariés de la Tour Eiffel, “Carte postal en couleurs/Polka pour deux cornets à pistons” (BBC Concert Orchestra; Bramwell Tovey, cond.)

Homosexuality

Poulenc became fully aware of his homosexuality in the late 1920s, and his intimate relationships, whether long-term or casual, were virtually all with men. His earliest openly gay relationships, however, would take its toll on Poulenc, as he told a friend that “he had lost his sense of identity.” Scholars speculate that “Poulenc associated gay sex with impurity and could therefore never truly accept an exclusively gay identity.”

The emotional complexity of his life was closely bound up with his creativity. According to Roger Nichols, “Poulenc was subject to a manic-depressive cycle, as he always rebounded from depression into phases of enthusiasm and was possessed successively by doubt and contentment.”

Francis Poulenc: Les Biches

New Seriousness

The 1930s saw the composition of Poulenc’s first religious works. This reawakening of religious faith and a new depth of seriousness in his music was probably inspired by two unrelated events in 1936. A fellow composer was killed in a violent car accident that left him decapitated, and immediately afterward, Poulenc visited the sanctuary of Rocamadour.

Francis Poulenc

As he later wrote, “A few days earlier, I’d just heard of the tragic death of my colleague … As I meditated on the fragility of our human frame, I was drawn once more to the life of the spirit. Rocamadour had the effect of restoring me to the faith of my childhood. This sanctuary, undoubtedly the oldest in France … had everything to captivate me. In my Litanies à la Vierge noire I tried to get across the atmosphere of peasant devotion that had struck me so forcibly in that lofty chapel.”

Francis Poulenc: Litanies à la Vierge Noire

The War Years

Poulenc was briefly called up to serve in the Second World War, but he spent the greater part of the war at his home in Noizay and in Paris. Poulenc was giving recitals with Pierre Bernac, and he set music verses by poets prominent in the French Resistance. His first opera, Les Mamelles de Tirésias, received its premiere in 1947 and was described as “high-spirited topsy-turvedydom concealing the deeper and sadder theme of France ravaged by war.”

Denise Duval

The soprano Denise Duval became Poulenc’s favourite female interpreter, and he called her “the nightingale who made me cry.” They undertook regular concert tours to the United States, and Poulenc was keenly aware of the important influence accorded to the radio. As such, he wrote and presented a series of broadcasts on French national radio. Shortly after the war, Poulenc had a brief affair with a woman, and their daughter Marie-Ange was born in 1946.

Francis Poulenc/ Denise Duval Perform Les mamelles de Tirésias, (Excerpts)

Distancing from the Mainstream

During the 1950s, Poulenc deliberately distanced himself from the composers of the younger generation who rejected Stravinsky and insisted on the singular validity of the Second Viennese School. He had met Schoenberg in Vienna in 1922 and concluded that the composer had reduced “poetry to atoms.” Poulenc strongly believed that “Berg had taken serialism as far as it could go.” Poulenc was quickly labelled “frivolous and a relic of the pre-war era.”

Poulenc’s religious music was frequently performed in the US and Britain, and Dialogues des Carmélites, commissioned by La Scala in Milan, rapidly gained international success. Poulenc died of a heart attack in Paris on 30 January 1963. The funeral took place at Saint-Sulpice a couple of days later, and Poulenc had decreed that none of his music was to be performed. He was buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery, alongside his family.

Francis Poulenc: Dialogues des Carmelites, “Salve Regina”

Legacy

Poulenc always expressed his deepest respect and admiration for composers of the past. He saw himself as part of a legacy of composers, particularly French composers. As he wrote, “Some people search for the unusual chord, the striking harmony, the new system. I am not one of those—something I’m neither ashamed nor proud of—I simply state a fact: there are some composers who have created their own syntax, others have arranged known materials in a new order, that’s all.”

Poulenc felt himself part of a larger musical legacy, “feeling free to use a chord by Wagner, Debussy, Schumann or even Franck if it expresses the emotional nuance he wanted to express.” As a scholar explains, “For Poulenc, the past was not a foreign object to appropriate or a challenging technical construct, but rather a part of his own identity.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter