On 2 November 1788, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach wrote to a friend, “Since 18 September I have been very ill with gout and other ailments. Now my health is beginning to improve.” However, this period of improvement was short-lived, as Bach died six weeks later on 14 December 1788. An obituary tribute appeared the following day in a local newspaper.

C.P. E. Bach

“Yesterday our city of Hamburg lost a very remarkable and famous man. At 10 in the evening, Herr Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Kapellmeister, and since 3 November 1767 Director of Music in this city, passed away. He was one of the greatest theoretical and practical musicians… and his compositions are masterpieces and will remain outstanding long after all the modern rubbish has been forgotten. In him the art of music has lost one of its greatest adornments.” Bach was buried in the Michaeliskirche in Hamburg, and a biographer tellingly wrote, “the reception history of Bach’s music started well before the day of his funeral and it took on two most extreme forms—unlimited acclaim and total neglect.”

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: String Symphony No. 3 in C Major, Wq 182/3

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart famously told Gottfried van Swieten, a diplomat, librarian, and esteemed patron of music, “Bach is the father. We are the children!” Surprisingly to us, Mozart did not have Johann Sebastian in mind, but he referenced Carl Philipp Emanuel instead. Joseph Haydn discovered the music of C.P.E. already in 1749, and according to his biographer “He did not come away from the instrument until he had played through them all, and anyone who knows me well must realize that I owe a great deal to Emanuel Bach, that I have understood him and studied him diligently. Emanuel Bach once paid me a compliment on this score to the Six Sonatas himself.”

“Frederick the Great’s Flute Concert in Sanssouci” by Adolph von Menzel, 1852, depicts Frederick the Great playing the flute as C. P. E. Bach accompanies on the keyboard © Wikipedia

Not to be outdone, Ludwig van Beethoven wrote to his publisher Breitkopf & Härtel on 26 July 1809, “I have only one or two of Emanuel Bach’s keyboard compositions, and yet they are some which every true artist should know, not only for the great enjoyment to be derived from them but also for the purpose of study.” While J.S. Bach cultural references are primarily theological, C.P.E.’s music represented the burgeoning secular discourse of the second half of the 18th century.

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Keyboard Sonata in C minor, Wq. 48/4 (Prussian Sonata No. 4) (Susan Alexander-Max, fortepiano)

For Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven, C.P.E was part of a common tradition, specifically in terms of his keyboard compositions. Much of Bach’s music had appeared in print during his lifetime, some of it simultaneously issued by multiple publishers. Without doubt, C.P. E. Bach had a significant impact on the three great Viennese Classical composers. A scholar wrote, “The music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven was nourished from so many sources that Bach’s role in the formation of their Classical style should be seen rather as that of a stimulus, albeit a most important one.” They saw C.P.E as a direct and most important link between the music of J.S. Bach’s and their own.

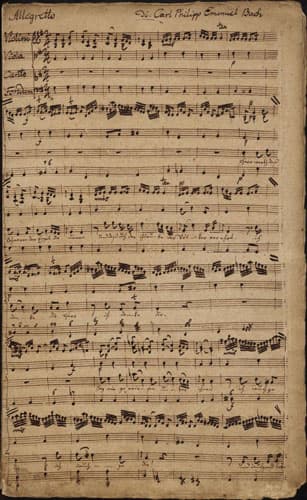

C.P. E. Bach’s manuscript

In fact, while Johann Sebastian tried to forge a direct connection between the musician and god, C.P.E. sought an emotional connection between the musician and the listener. While C.P.E.’s compositions were still described as “models and exercises in the expression of deep emotions in 1799,” his works gradually passed into oblivion. Within the early Romantic musical aesthetic, Bach represented a defining stage in the history of music, and he was considered a composer who had simultaneously enriched and impoverished music.

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Cello Concerto in A minor, Wq 170

As a contemporary theorist writes, “Enriched in that he imitated instrumentally the cantabile melody of applied music and thereby rescued music from its rhetorical limitations. However, by his dazzling virtuosity of figural manipulation without adequate substance or truth, he has impoverished composition through over-simplification of the musical language.” Robert Schumann was looking at the idea of historical continuity when he wrote, “As a keyboard composer C.P.E. Bach was a pioneer, for his works, with their free improvisatory dynamism, while lacking the greatness of his father’s music, are to be regarded as the first in this style that are connected with the period of Haydn and Mozart.”

Schumann, noticing the progressive features of C.P.E. wrote, “he filed, he refined, he caused a beautiful cantilena to flow through the then predominating harmony, yet as a creative musician he remained very far behind his father.” And Felix Mendelssohn went as far as describing him “as a dwarf among the giants.” When the pianist Hans von Bülow edited the keyboard works of C.P.E in 1860, he wrote to his friend Felix Draeseke, “I am in the process of editing some of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s keyboard sonatas. The work is very dry and it puts me in a bad mood.” It was not until 1905 that the Belgian musicologist Alfred Wotquenne produced the Thematic Catalogue of the works by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, “a work which is still indispensable for both scholars and performers.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter