Compositions for Films and the Concert Hall

On a long rainy day, with typhoon winds lashing the windows, I love nothing better than curling up with my favorite snacks in front of the Television. Basically, I will binge-watch an entire Netflix series, or if the mood is right, settle down to some historical epics. One of my all-time favorite religious epics is “Ben Hur,” which screened in 1959. The film won a record 11 Oscars, but not simply because of the memorable battle scenes and chariot races. It seems to me that credit should also be given to Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995), the composer of the wonderful musical score.

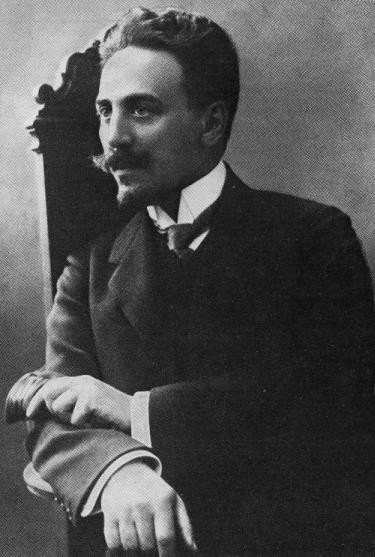

Miklós Rózsa

In fact, Rózsa wrote scores for about 100 films between 1937 and 1982, earning him 17 Oscar nominations. While Rózsa is rightfully famous for his luscious film scores, he simultaneously, and unbeknownst to me, crafted many compositions for the concert hall. He actually called it his “double life,” and it all started in Budapest in 1907.

Miklós Rózsa: Theme, Variations and Finale, Op. 13 (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Rumon Gamba, cond.)

Raised in the capital city of Hungary and on his father’s rural estate in nearby Tomasi, Rózsa demonstrated a great talent for music from an early age. He initially studied piano with his mother, a classmate of Béla Bartók, and the violin and viola with his uncle Lajos Berkovits. By the age of seven, Rózsa was composing his own works. In his youth, Rózsa was deeply influenced by Hungarian folk music, which he experienced on his family’s estate. He writes, “The music was all around me; I would hear it in the fields when the people were at work, in the village as I lay awake at night; and the time came when I felt I had to try to put it down on paper and perpetuate it.”

Rózsa was never a methodical folk-song collector like Bartók and Kodály, and he rarely resorting to direct quotations of folk melodies. However, as has been explained, “he absorbed the folk idiom so completely and deeply that it became an integral part of his mature musical language, stamped indelibly in one way or another on virtually every bar ever put on paper.”

Miklós Rózsa: Duo, Op. 7 (Philippe Quint, violin; William Wolfram, piano)

Initially, Rózsa was looking to study at the Budapest Franz Liszt Academy, but he was fearful that its director Zoltán Kodály would not allow him to find his musical voice. It was a long and hard-fought battle, but eventually, his father agreed to let Miklós enroll at the University of Leipzig as a chemistry major with a minor in musicology.

Miklós Rózsa conducting

Rózsa immediately knew that he wanted to be a composer, and one year later he enrolled at the Leipzig Conservatory. He studied composition with Hermann Grabner, who had succeeded Max Reger, choral music with Karl Straube at the Thomaskirche, and musicology with Theodor Kroyer. At the time of his graduation from the Conservatory in 1928 Rózsa already had two works, a string trio, and a piano quintet, published by the firm Breitkopf and Härtel. His compositions were promoted and performed throughout Europe, and as far as his compositional career was concerned, the sky was the limit.

Miklós Rózsa: Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 2 (Endre Granat, violin; Sheldon Sanov, violin; Milton Thomas, viola; Nathaniel Rosen, cello; Leonard Pennario, piano)

Rózsa left Leipzig for Paris in 1931, and two years later produced what was to become his first, major successful orchestral work, the Theme, Variations and Finale, Op. 13. While in Paris he met the Swiss composer Arthur Honegger who introduced Rózsa to the idea of writing music for films as a way of making a living. Initially, he wrote a number of popular songs under the pseudonym of Nic Tomay, but then left for London in search of better opportunities. Rózsa was hired to compose his first film score for Knight Without Armour for London Films under the Hungarian-born producer Alexander Korda in 1937. In due time, Rózsa accompanied Korda to Hollywood in 1940 to compose the score to The Thief of Bagdad, and he was soon in great demand as a freelance film composer and conductor.

Miklós Rózsa: The Thief of Baghdad Suite (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Rumon Gamba, cond.)

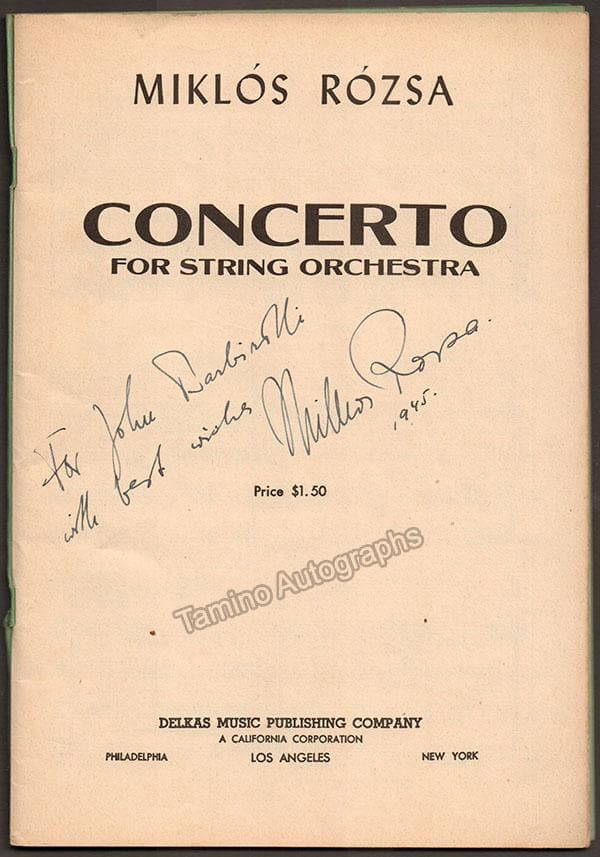

Miklós Rózsa signed score cover of his Concerto for String Orchestra

Rózsa quickly became part of a thriving community of musical émigrés, including composers such as Toch, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Korngold, as well as performers such as Piatigorsky and Heifetz. Rózsa had drafted a violin concerto during his student days in Leipzig, but it was never published. Taking a summer break from his work for MGM he decided to compose a violin concerto by approaching Jascha Heifetz. Heifetz was interested but was looking for a trial first movement before making a decision. Rózsa was unsure of how to proceed, as Heifetz had once approved the opening pages of the Schoenberg Violin Concerto before refusing to play the full work. However, Rózsa set to work and completed the concerto in only six weeks. Heifetz was happy, and he premiered the work in Dallas on 15 January 1956. I actually had no idea that Rózsa composed four concertos for solo instruments and orchestra, including a Cello Concerto for János Starker. As a critic writes, “the music of Miklós Rózsa tempers an arch romanticism with an innate classicism. Perhaps this reflects the fact that he was born in Hungary but trained at the Leipzig Conservatory. It is true both of his film music, where romanticism is rather more to the fore, and his concert works, where form and substance never fail to satisfy.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Miklós Rózsa: Violin Concerto, Op. 24 (Anastasia Khitruk, violin; Russian Philharmonic Orchestra; Dmitry Yablonsky, cond.)