In many of Wagner’s theoretical writings, such as “Die Kunst und die Religion” (Art and Religion – 1849), “Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft” (The Artwork of the Future – 1849) and “Oper und Drama” (Opera and Drama – 1852), the concept of the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ — the totality of the work of art — became the central focus , which Wagner subsequently made the basis for his compositions.

In many of Wagner’s theoretical writings, such as “Die Kunst und die Religion” (Art and Religion – 1849), “Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft” (The Artwork of the Future – 1849) and “Oper und Drama” (Opera and Drama – 1852), the concept of the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ — the totality of the work of art — became the central focus , which Wagner subsequently made the basis for his compositions.

According to Wagner, the ‘Zersplitterung der Kűste’ (the Split between the Arts) had occurred in Greek antiquity, with word, music and dance originally existing in perfect harmony. Initially, in the perfect Greek state, Greek tragedy embodied this harmony, but with the fall of the ‘Athenian Polis’, the arts started to diverge. For Wagner, (and this explains his youthful ‘revolutionary’ fervor during the revolutions of 1848) one should aspire to create a perfect society in which the perfect harmony of the work of art could again exist.

Focusing specifically on opera, Wagner criticized many of the traditional opera libretti, in which, he said “the action was a roughly constructed framework which only existed to poorly motivate pathetic situations” (“… daß die Handlung ein roh gezimmertes Gerüst darstelle, das zu nichts anderem bestimmt sei, als pathetische Situationen notdürftig zu motivieren”) — interspersed with arias which dominated the libretto. For him, opera and drama had to be re-united. Here, he approached Baudelaire’s concept of ‘synesthesia’, which I addressed in my previous Interlude article ‘Richard Wagner and Paris’, where all of the senses, acting in harmony, are awakened and lead to more profound appreciation and experience.

Focusing specifically on opera, Wagner criticized many of the traditional opera libretti, in which, he said “the action was a roughly constructed framework which only existed to poorly motivate pathetic situations” (“… daß die Handlung ein roh gezimmertes Gerüst darstelle, das zu nichts anderem bestimmt sei, als pathetische Situationen notdürftig zu motivieren”) — interspersed with arias which dominated the libretto. For him, opera and drama had to be re-united. Here, he approached Baudelaire’s concept of ‘synesthesia’, which I addressed in my previous Interlude article ‘Richard Wagner and Paris’, where all of the senses, acting in harmony, are awakened and lead to more profound appreciation and experience.

Richard Wagner: Tristan und Isolde – Act III: Prelude (Bayreuth Festival Orchestra; Peter Schneider, cond.)

Richard Wagner: Tristan und Isolde – Act III Scene 3: Mild und leise wie er lächelt (Isolde) (Iréne Theorin, soprano; Bayreuth Festival Orchestra; Peter Schneider, cond.)

In the beginning of the 19th century, the Romantic movement in literature and the arts, which influenced Wagner’s ideas of the ‘Musikdrama’, had already diverged from the static, classical art forms of the 18th century (the 24 hour rule, the unity of time, action and space — see my previous Interlude article on ‘The Classical Age in Literature, Art and Music’). In his vision of the Gesamtkunstwerk, Wagner saw it as his mission to reunite the arts — music and fiction, enhanced by dance and gesture, were to be fully developed, and on an equal basis. The music of the orchestra should express messages appealing to the listener’s subconscious which then elicits emotional reactions, enhanced by the sensuality of accompanying gestures and dance. Music and word are then unified in what Wagner called, “Versmelodie” (melody of verse), i.e. the unification of spoken elements and poetic, musical creation. Whereas spoken language alone addresses the intellect and music evokes feelings, the “Versmelodie” creates a synthesis between both, “… specifically between absence and presence, between intellect/thought and feeling” (“In der Versmelodie verbindet sich nicht nur die Wortsprache mit der Tonsprache, sondern auch das von diesen beiden Organen ausgedrűckte, nämlich das Ungegenwärtige mit dem Gegenwärtigen, der Gedanke mit der Empfindung”, Richard Wagner, Oper und Drama, p. 338). Wagner then created musical ‘leitmotifs’, specific to characters and situations which create a unity within the work and other works to follow. A good example is the leitmotif for Tristan in ‘Tristan und Isolde’, where the so-called ‘Tristan accord’, bitonal in character, constantly changes from major to minor keys, and so reflects the ambivalence and changes of Tristan’s subconscious feelings. We can consider Wagner’s ‘leitmotifs’ as acoustic controls, in that they evoke in the listener the foreboding of actions to come or remembrances of actions which have already occurred (“Der lebengebende Mittelpunkt des dramatischen Ausdruckes ist die Versmelodie des Darstellers: auf sie bezieht sich als Ahnung die vorbereitende absolute Orchestermelodie; aus ihr leitet sich als Erinnerung der Gedanke des Instrumentalmotives her” p. 349). Wagner’s ‘leitmotifs’ create emotional guideposts throughout his operas and seem to construe action in an internally motivated fashion – this applies particularly to his ‘Ring’ cycle.

In the beginning of the 19th century, the Romantic movement in literature and the arts, which influenced Wagner’s ideas of the ‘Musikdrama’, had already diverged from the static, classical art forms of the 18th century (the 24 hour rule, the unity of time, action and space — see my previous Interlude article on ‘The Classical Age in Literature, Art and Music’). In his vision of the Gesamtkunstwerk, Wagner saw it as his mission to reunite the arts — music and fiction, enhanced by dance and gesture, were to be fully developed, and on an equal basis. The music of the orchestra should express messages appealing to the listener’s subconscious which then elicits emotional reactions, enhanced by the sensuality of accompanying gestures and dance. Music and word are then unified in what Wagner called, “Versmelodie” (melody of verse), i.e. the unification of spoken elements and poetic, musical creation. Whereas spoken language alone addresses the intellect and music evokes feelings, the “Versmelodie” creates a synthesis between both, “… specifically between absence and presence, between intellect/thought and feeling” (“In der Versmelodie verbindet sich nicht nur die Wortsprache mit der Tonsprache, sondern auch das von diesen beiden Organen ausgedrűckte, nämlich das Ungegenwärtige mit dem Gegenwärtigen, der Gedanke mit der Empfindung”, Richard Wagner, Oper und Drama, p. 338). Wagner then created musical ‘leitmotifs’, specific to characters and situations which create a unity within the work and other works to follow. A good example is the leitmotif for Tristan in ‘Tristan und Isolde’, where the so-called ‘Tristan accord’, bitonal in character, constantly changes from major to minor keys, and so reflects the ambivalence and changes of Tristan’s subconscious feelings. We can consider Wagner’s ‘leitmotifs’ as acoustic controls, in that they evoke in the listener the foreboding of actions to come or remembrances of actions which have already occurred (“Der lebengebende Mittelpunkt des dramatischen Ausdruckes ist die Versmelodie des Darstellers: auf sie bezieht sich als Ahnung die vorbereitende absolute Orchestermelodie; aus ihr leitet sich als Erinnerung der Gedanke des Instrumentalmotives her” p. 349). Wagner’s ‘leitmotifs’ create emotional guideposts throughout his operas and seem to construe action in an internally motivated fashion – this applies particularly to his ‘Ring’ cycle.

AEG Turbine Factory designed by Peter Behrens

© metalocus.es

It is in this sense that we can make the connection to Marcel Proust’s writing, and specifically to his epic work ‘A la Recherche du Temps Perdu’ (In Search of Lost Time). Proust was an ardent admirer of Wagner and we find many references to Wagner in his novels. ‘La petite Sonate de Vinteuil’ in ‘Du Côté de Chez Swann’ (‘Swann’s Way’) is the leitmotif for Swann’s love for Odette, but later reappears as the leitmotif in the relationships between the narrator and Albertine, and Gilberte, Swann’s daughter. Here too, the distinction is made between intellect and feelings:

“Et le plaisir que lui donnait la musique (….) ressemblait en effet, à ces moments-là, au plaisir qu’il aurait eu à experimenter des parfums, à entrer en contact avec un monde (…) qui nous semble sans forme parce que nos yeux ne le perçoivent pas, sans signification parce qu’il échappe à notre intelligence…”

“Et le plaisir que lui donnait la musique (….) ressemblait en effet, à ces moments-là, au plaisir qu’il aurait eu à experimenter des parfums, à entrer en contact avec un monde (…) qui nous semble sans forme parce que nos yeux ne le perçoivent pas, sans signification parce qu’il échappe à notre intelligence…”

(And the pleasure which music gave him (…) at those moments resembled in effect the pleasure with which he would experiment in scents/perfumes, to enter into contact with a world (…) which seems to us without form, because our eyes do not perceive it, without meaning, because it escapes our intelligence…)

For Proust, just as for Baudelaire and Wagner, this distinction between intellect and feelings has to be overcome through the appeal to the senses, which allows him, and in turn the reader or listener, to access this other world — the world of art, music, painting and literature. Whether it is the ‘Sonate de Vinteuil’, the ‘Madeleine steeped in the cup of tea’, the ‘paintings of the Impressionist painter, Elstir’ (who proclaimed like Monet, “not to paint the object, but the effect it produces”), the ‘uneven steps in the street recalling the beauty of Venice’, their very essence and recurring memory (leitmotifs) become the search and recovery of lost time — which then in turn, for Proust, becomes the act of writing — the act of creation. The recurring themes/leitmotifs in Proust’s cyclical novel replicate those in Wagner’s Ring cycle, ‘Der Ring des Nibelungen’.

For Proust, just as for Baudelaire and Wagner, this distinction between intellect and feelings has to be overcome through the appeal to the senses, which allows him, and in turn the reader or listener, to access this other world — the world of art, music, painting and literature. Whether it is the ‘Sonate de Vinteuil’, the ‘Madeleine steeped in the cup of tea’, the ‘paintings of the Impressionist painter, Elstir’ (who proclaimed like Monet, “not to paint the object, but the effect it produces”), the ‘uneven steps in the street recalling the beauty of Venice’, their very essence and recurring memory (leitmotifs) become the search and recovery of lost time — which then in turn, for Proust, becomes the act of writing — the act of creation. The recurring themes/leitmotifs in Proust’s cyclical novel replicate those in Wagner’s Ring cycle, ‘Der Ring des Nibelungen’.

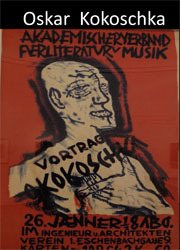

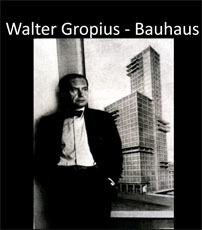

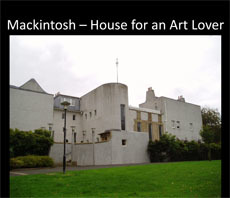

Wagner’s concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk also influenced many other artists of the 19th and 20th centuries. The Arts and Crafts Movements in Scotland (Charles Rennie Mackintosh) and England (William Morris), the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops) in Austria (Gustav Klimt, Josef Hofmann, Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos), the Bauhaus (Walter Gropius in Dessau/Weimar — later in Berlin and Chicago) and the Secession in Dresden (Die Brücke – The Bridge), all were concerned with the situation of the artist-craftsman in the newly and rapidly developing industrial society with its production of ready-made products which would threaten their art and livelihood. All of their efforts were directed toward re-creating an artistic environment where all of the arts would come together. The architecture of their time (the architect Peter Behrens would speak of his Turbine Factory) as a cathedral in steel and glass) would now reflect their aesthetic not only on the exterior, but within their museums, private houses, shops and cafés as well, in which all elements were coordinated and furniture, fabrics, housewares, books, jewelry and clothes created a beautifully integrated environment. Oskar Kokoschka’s poster advertises a speaking engagement on literature and music (even though Kokoschka was a painter), and Gustav Klimt paints his vision of philosophy, basing it on Nietzsche’s Midnight Song in ‘Zarathoustra’—“Oh Mensch, gib acht, was spricht die tiefe Mitternacht …” (O man take heed, what does the deep midnight say…), which Gustav Mahler then uses in his Third Symphony.

Wagner’s concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk also influenced many other artists of the 19th and 20th centuries. The Arts and Crafts Movements in Scotland (Charles Rennie Mackintosh) and England (William Morris), the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops) in Austria (Gustav Klimt, Josef Hofmann, Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos), the Bauhaus (Walter Gropius in Dessau/Weimar — later in Berlin and Chicago) and the Secession in Dresden (Die Brücke – The Bridge), all were concerned with the situation of the artist-craftsman in the newly and rapidly developing industrial society with its production of ready-made products which would threaten their art and livelihood. All of their efforts were directed toward re-creating an artistic environment where all of the arts would come together. The architecture of their time (the architect Peter Behrens would speak of his Turbine Factory) as a cathedral in steel and glass) would now reflect their aesthetic not only on the exterior, but within their museums, private houses, shops and cafés as well, in which all elements were coordinated and furniture, fabrics, housewares, books, jewelry and clothes created a beautifully integrated environment. Oskar Kokoschka’s poster advertises a speaking engagement on literature and music (even though Kokoschka was a painter), and Gustav Klimt paints his vision of philosophy, basing it on Nietzsche’s Midnight Song in ‘Zarathoustra’—“Oh Mensch, gib acht, was spricht die tiefe Mitternacht …” (O man take heed, what does the deep midnight say…), which Gustav Mahler then uses in his Third Symphony.

In those glorious years of the Fin-de-Siècle culture many of these architects, artist-craftsmen, painters, writers and musicians would follow Wagner’s inspiration, creating objects of beauty in their respective fields, reaching across different domains, and, in every sense, achieving the concept of the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter