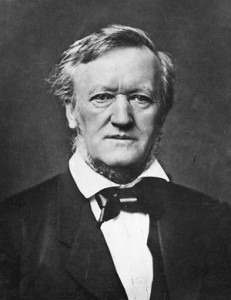

Richard Wagner

In the 19th century, Paris was one of the most important music capitals of Europe. Richard Wagner, during his ‘Wanderjahre’ (years of wandering from Riga to London, Dresden and Zűrich – mainly to escape his various creditors), attempted several times (from about 1839 to 1861) not only to make Paris his home, but to introduce his works to the general French public — unsuccessfully, as we shall see. But over the course of these many years, Wagner was at least able to establish contacts with leading opera directors, conductors and composers, amongst them Franz Liszt, whom he had already befriended earlier in Dresden and Weimar, and Meyerbeer, Berlioz, Rossini and Gounod. The leading writers and artists at the time, in particular the poets Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé, were not only part of his circle of friends, but would defend Wagner’s music in published articles.

Charles Baudelaire

Initially, Wagner introduced his works to the Parisian public, as excerpts from Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Tristan and Isolde, and The Flying Dutchman, in three concerts in the Théâtre des Italiens, which were attended by Baudelaire and Liszt, as well as by many of the contemporary literary and musical greats of the time, and to which the general press reacted positively at first. Subsequently, with the support of the wife of the Austrian Ambassador, Princess Pauline Metternich, Emperor Napoléon III ordered the presentation of the full opera ‘Tannhäuser’ at the Paris Opera House. After 164 rehearsals, only three presentations took place, on March 13th, 18th and 24th, 1861, after which Wagner, deeply disappointed and hurt by its negative reception by the general public, withdrew his work. Wagner had refused to insert a ballet in the second act of the opera, which had been standard opera practice dating from the 17th century, and was still expected by the public at the time. Wagner had merely extended the scene of the ‘Bacchanal’ in the first act into a sort of ballet scene, which elicited shouting and whistling by the members of the ‘Jockey Club’ in attendance, who objected to opera in which music and drama were closely linked and standard rules were broken. Wagner’s new concepts in opera presentation were rejected by the general public, even though, as Baudelaire would mention in his article, the public could not even hear it due to their own loud outbursts. In the same article, titled “Richard Wagner et Tannhäuser à Paris”, published on April 1, 1861 in the ‘Revue Européenne’, Baudelaire defended Wagner fiercely, deriding the members of the public whose mistresses, he said, were found amidst the dancers of the conventional ballets scenes, who were present only to be admired on stage. He writes:

“Gardez votre harem et conservez-en religieusement les traditions; mais faites-nous donner un théâtre où ceux qui ne pensent pas comme vous pourront trouver d’autres plaisirs mieux accommodés à leur goût. Ainsi nous serrons débarrassés de vous et vous de nous, et chacun sera content”. (“Keep your harem and conserve religiously the traditions; but give us a theater where those who do not think like you find other pleasures better accommodated to their taste. Thus we would be rid of you and you of us, and everyone would be happy”).

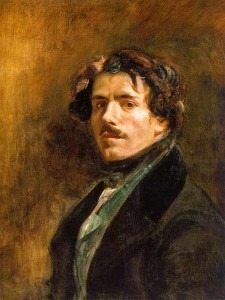

Eugène Delacroix

Tannhauser

Overture – Act I Scene 1: Naht euch dem Strande (Chorus)

Baudelaire was familiar with Liszt’s articles and his later monograph (‘Wagner’s Tannhäuser’, published in 1849 in Leipzig), in which Liszt had given a descriptive analysis of the first Weimar performance of Tannhäuser, which had taken place on February 16, 1849. Liszt emphasized in particular Wagner’s new concept of conceiving the overture as a closed, independent symphonic form, and then gave an overall assessment of the score’s significance as the beginning of a new era of dramatic art. In his own article, Baudelaire admired and quoted the beginning of Liszt’s monograph, where he discussed Wagner’s chants of the pilgrims and the songs of the sirens:

“At first in quiet, slow pulsations, but gradually overflooded by the insinuating modulations of the voices… seductive mingling of pleasure and unrest… until the enchantment reaches its climax… it leaves no chord within us silent, but sets every fiber of our being in vibration; the religious theme gradually comes in again, subdues to itself all these sounds, and melts them together into a sublime harmony and unfolds the wings of the triumphal hymn to their fullest breath”.

For Baudelaire, Wagner’s work embodies “an awareness of the magical power of suggestion of music”, which replicated the musicality of many of his own poems in ‘Les Fleurs du Mal’ (The Flowers of Evil), such as in the following poem:

| Harmonie du Soir Voici venir les temps où vibrant sur sa tige Chaque fleur s’évapore ainsi qu’un encensoir; Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir; Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige! Chaque fleur s’évapore ainsi qu’un encencoir; Le violon frémit comme un Coeur qu’on afflige; Un coeur tendre, qui hait le néant vaste et noir, | Evening Harmony Here come the times where vibrating on its stem Each flower evaporates like a censer; Sounds and perfumes turn in the evening air Melancholic waltz and languorous vertigo! Each flower evaporates like a censer; The violin trembles like an afflicted heart; Melancholic waltz and languorous vertigo! The sky is sad and beautiful like a large altar. The violin trembles like an afflicted heart; A tender heart, which hates vast and black nothingness! The sun has drowned in its blood which congeals. A tender heart, which hates vast and black nothingness, |

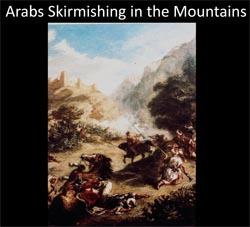

The repetitive lines in the poem in each of the verses create a musical rhythm like a waltz, repeating and adding new elements, creating the ‘synesthesia’ of color, sound and scent – a concept not only vitally important in the construction of his poems (many of which carry the titles ‘chant’ or ‘chanson/song’), but a construct which Baudelaire would also see as the basis for the paintings of Delacroix.

The repetitive lines in the poem in each of the verses create a musical rhythm like a waltz, repeating and adding new elements, creating the ‘synesthesia’ of color, sound and scent – a concept not only vitally important in the construction of his poems (many of which carry the titles ‘chant’ or ‘chanson/song’), but a construct which Baudelaire would also see as the basis for the paintings of Delacroix.

The works of Eugène Delacroix were rejected by the French public just as were the operas of Wagner. Delacroix, considered by Baudelaire a ‘romantic’ painter, had broken the rules in painting, as Wagner had broken them in music, and Baudelaire himself had in his poetry. In one of the verses of his poem Les Phares (Lighthouses), Baudelaire writes about Delacroix, whom he considered as one of the ‘phares’, i.e., one of the ‘shining lights’ in painting:

| Delacroix, lac de sang hanté de mauvais anges, Ombragé par un bois de sapins toujours verts, Où, sous un ciel chagrin, des fanfares étranges Passent, comme un soupir, étouffé de Weber. | Delacroix, lake of blood haunted by evil angels, Sheltered by woods of evergreen trees Where, under a woeful sky, strange fanfares |

Delacroix’s paintings, with their vivid primary colors, apparent brushstrokes, off-centered perspective, with their subject matter both from the classical past and contemporary life inspire one to dream – relating to what Baudelaire considers the highest of the arts: music.

Delacroix’s painting, Wagner’s music and Baudelaire’s poetry, as well as the works of Mallarmé and Proust later in the century, see artistic creation as ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (totality of the work of art), where all of the elements come together and have to be seen as part of a beautiful totality. Baudelaire’s “Fleurs du Mal” (Flowers of Evil) puts into play the same ‘correspondences’ – musical dreams which project all of his passions. Wagner’s music is for him “like a blinding climax of color, shining in all its brightness and radiating magnificence, sparkling brilliance which died down quickly, like a faint celestial light”.

Delacroix’s painting, Wagner’s music and Baudelaire’s poetry, as well as the works of Mallarmé and Proust later in the century, see artistic creation as ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (totality of the work of art), where all of the elements come together and have to be seen as part of a beautiful totality. Baudelaire’s “Fleurs du Mal” (Flowers of Evil) puts into play the same ‘correspondences’ – musical dreams which project all of his passions. Wagner’s music is for him “like a blinding climax of color, shining in all its brightness and radiating magnificence, sparkling brilliance which died down quickly, like a faint celestial light”.

Here again, Baudelaire agrees with Franz Liszt in that:

“Wagner… peu content du pouvoir qu’elle [la musique] excerce sur les coeurs en y réveillant toute la gamme des sentiments humains, il lui rend possible d’inciter nos ideés, de s’adresser à notre penseé, de faire appel à notre réflexion, et la dote d’un sens moral et intellectuel…” (Wagner… little content with the power of music and the effect it has on hearts, awakens there all of the range of human sentiments… which make it possible for him to incite our ideas, to address our thoughts, to demand our reflection, and so endows it [music] with a moral and intellectual sense…).

Despite the fact that none of Wagner’s operas were performed in Paris again in the 19th century, Wagner’s fame continued to grow there. Many French aristocrats and wealthy bourgeoisie would travel to Bayreuth to hear his works. Contributing to Wagner’s fame in France was the ‘Révue Wagnerienne’, published regularly between 1885 and 1887, in which many French writers, amongst them Mallarmé, Verlaine, Huysmans, Nerval, and Mendès, continued to write about Wagner and Wagner-themes, discussing Wagner’s literary and philosophical relevance to their own aesthetic, which was not only relevant for their own work in their own time, but would influence the aesthetic of the new century as well.