© www.richtercompetition.com

“…I don’t play for the audience, I play for myself, and if I derive any satisfaction from it, then the audience, too, is content.”

Sviatoslav Richter (1915-1997)

20th March 2015 marks the centenary of the birth of Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter. Widely regarded as one of the greatest pianists of the twentieth century, Richter was, unusually, self-taught until he entered the Moscow Conservatory at the age of 22, where he undertook formal piano studies with Heinrich Neuhaus (who also taught Emil Gilels and Radu Lupu). It is said that Neuhaus declared Richter to be “the genius pupil, for whom he had been waiting all his life”, while acknowledging that he taught Richter “almost nothing.”

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 13 in A Major, Op. 120, D. 664 – III. Allegro (Sviatoslav Richter, piano)

Richter was, and continues to be, acclaimed for the depth of his interpretations, virtuoso technique, and vast repertoire. Much of the fascination with Richter derives from the fact that we in the West knew so little about him until he was well into middle age. He played at Stalin’s funeral, but for political reasons he was not permitted to travel abroad until 1960, when he gave his first international concert in Helsinki. His first London concert was in 1961. His pianism combined astonishing technical mastery with a bold, wide-ranging musical imagination, profound insight and incomparable colourings, sound and dynamic shadings. He could project the inner voices of Schubert’s sonatas (which he particularly loved) and played the music of J.S. Bach with great clarity and independence. He was averse to the idea of the “career-musician”, and preferred to forge his own path in terms of programmes, concert bookings and the obligations of touring and recording. He enjoyed playing in small venues, off the beaten track, and during the war he performed in the Russian provinces, playing on indifferent school and community hall pianos which forced him to think beyond the instrument. Though the sound of the piano could not be changed, he believed he could draw the audience along with him through his extraordinary imaginative powers. Fellow pianist Glenn Gould described Richter as “one of the most powerful communicators the world of music has produced in our time”.

Johannes Brahms: Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Major, Op. 78 – I. Vivace ma non troppo (Oleg Kagan, violin; Sviatoslav Richter, piano)

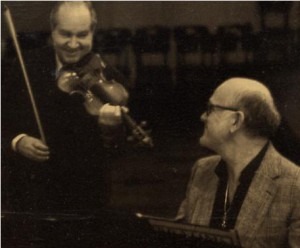

With David Oistrakh

© derricksblog.files.wordpress.com

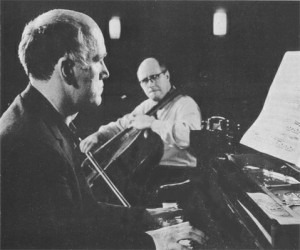

In addition to his solo work, he was a committed chamber musician and formed lasting musical friendships and collaborations with artists such as cellists Mstislav Rostropovich and Natalia Gutman, violinists David Oistrakh and Oleg Kagan, baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, pianist Elisabeth Leonskaja, and composer Benjamin Britten (watch the film of Richter performing Mozart duos with Britten and their pleasure in the music and one another’s company is delightfully evident). In 1963 he established an annual chamber music festival at Grange de Meslay near Tours in the Loire Valley in France, which continued for 30 years. He was also a voracious concert-goer and listener to LPs: his notebooks (published in Sviatoslav Richter: Notebooks and Conversations) bear witness to his appreciation of a wide variety of music, about which he wrote with knowledge and enthusiasm.

Sergei Prokofiev: Visions Fugitives – No. 6 Con Eleganza (Sviatoslav Richter, piano)

With Mstislav Rostropovich

© fischer.hosting.paran.com

Richter’s repertoire was huge and encompassed music ranging from Handel and Bach to Szymanowski, Berg, Webern, Stravinsky, Bartók, Hindemith, Britten, and Gershwin. He claimed to have “around eighty different programmes, not counting chamber works” in his repertory. There are very few concert pianists active today who can claim to have a similarly vast repertoire in the fingers. Only perhaps Italian pianist Maurizio Pollini can match Richter in the breadth of his repertoire and his willingness to tackle the canon of western classical music from Bach to Boulez.

Those who were fortunate enough to hear Richter live talk of the intensity of his performances, especially in his later years. The auditorium would be almost completely dark, the music desk lit by a single lamp, the pianist hardly visible:

“I… play in the dark, to empty my head of all non-essential thoughts and allow the listener to concentrate on the music rather than on the performer. What’s the point of watching a pianist’s hands or face, when they only express the efforts being expended on the piece?” (source: Bruno Monsaingeon Sviatoslav Richter: Notebooks and Conversations)

His concerts were described as hypnotic, eclectic, spontaneous, unpredictable, emotionally exhausting (for the audience at least; not so Richter who seemed to feed off the delirious applause). Yet he shunned the limelight, claiming “I cannot live up to such a legend, I’m just a normal human being who plays the piano.”

Richter continued to perform until two years before his death. He died in Moscow from a heart attack on August 1, 1997 aged 82. At the time of his death, he was rehearsing music by one of his favourite composers: Schubert’s Fünf Klavierstücke, D459. His performances live on in people’s imagination and memories, and in the vast legacy of recordings, most of which testify to his greatness.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Richter resources:

Richter – the Enigma – 1998 film by Bruno Monsaingeon which reveals the complexity of Richter’s personality

Monsaingeon, Bruno (2001). Sviatoslav Richter: Notebooks and Conversations. Princeton University Press

Rasmussen, Karl Aage (2010). Sviatoslav Richter – Pianist. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Interesting that in his later years he chose to perform using music scores, even though he knew the music thoroughly. I read somewhere that it was because he wished to be scrupulously faithful to the composers’ scores

Actually it was because he lost his perfect pitch and he used the score for security. Older people almost always lose their sense of perfect pitch and if you’ve relied on it for your memory when you’re younger you have to switch to using music.

He lost his way playing transcendental etudes in Tours, so this might account for the change. The same thing happened to my teacher in Dubrovnik, but he stubbornly refused to use music. The results were embarrassing. I use the music for recitals now, but for a different reason,. My memory is not bad …. but just play better with the score in front of me.

You mean Liszt’s transcendental etudes? Which year did that happen? I tried several times with no avail to find more information when and where this incident happened.

I don’t know the year, but did hear a recording of them on YouTube. Found his readings a bit harsh. The harmonies du sour is good and feux follets was amazing!!

He lost his perfect pitch and the scores were essential.

It must have been awful for him, to have his father shot dead in Odessa, then have this obnoxious lunatic (name withheld), claim to be his father and take the credit for his talent and education. I met him on one occasion and was rather tongue-tied. We spoke in French and he was absolutely charming. Incomparable musician.

I heard him many times and mostly before the rather theatrical blacked out halls, Anglepoise lamp and use of scores. He tried to make a virtue of these things and indeed his later programmes published a rationale as to why he played like this. In truth playing from scores was in answer to his deteriorating memory – a condition which I believe caused him considerable distress and resulted in him seeking psychiatric help in Paris (?). His later playing was somewhat grey, incredibly serious and made few concessions to the ‘pleasure factor.’ Putting all this aside he was (and remains) the greatest pianist I ever heard – sound, integrity and technique beyond compare, especially integrity. I met him after a recital he gave in Cheltenham (dull programme alas), we spoke in German and I told him that a student of mine was his page turner and was very nervous. “Warum?” said Richter with his famous shrug!

I have heard way too many fine performances by players using the score to criticize such use . The ancients played from score, or improvised upon a theme…

Your facebook foto, S R with Charles Munch, Beethoven PC1—C M especially wanted to record it with S R, so brought him to Boston from then USSR…note the vigor of the great interpretation, requiring S R.