It’s a loaded question, and more than a little silly. When it comes to music and art, of course, greatness is extremely subjective.

However, it’s just plain fun to look at such a list, seeing which pieces went into print first and when, as well as what age each composer was when their first pieces were published.

Today, we’re looking at works that seven of the great composers decided to label as their opus one.

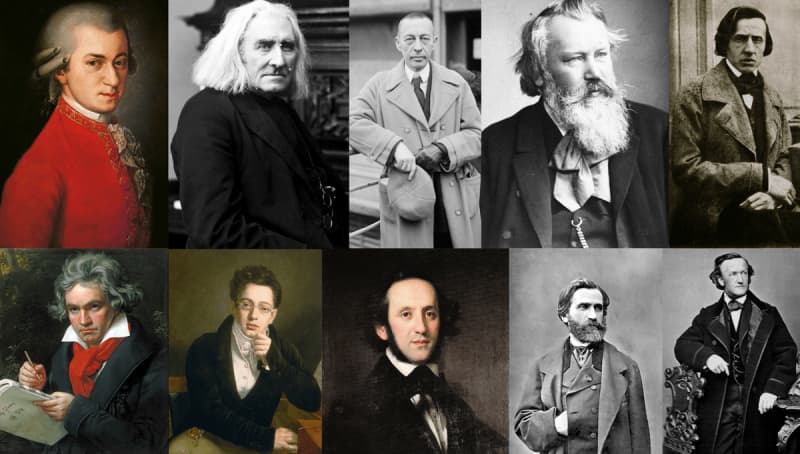

© abc.net.au

Beethoven: Piano Trios, Op. 1

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Op. 1 consists of three charming trios for piano, violin, and cello. These three piano trios were published in 1795, when Beethoven was 24 years old.

All three were premiered in the home of Prince Lichnowsky, a noted aristocratic patron of both Mozart and Beethoven.

Christian Horneman: Beethoven, 1803 (Beethovenhaus Bonn)

In 1805, Beethoven would go so far as to call Lichnowsky “one of my most loyal friends and promoters of my art.” That said, he and Beethoven fell out with each other within the year, a feud that ended with Beethoven smashing a bust of the prince to pieces.

Interestingly, these were not the very first works Beethoven published (that would be his Dressler Variations for keyboard). But he didn’t want to label those variations as an official opus; he wanted that particular honour to go to these three piano trios instead.

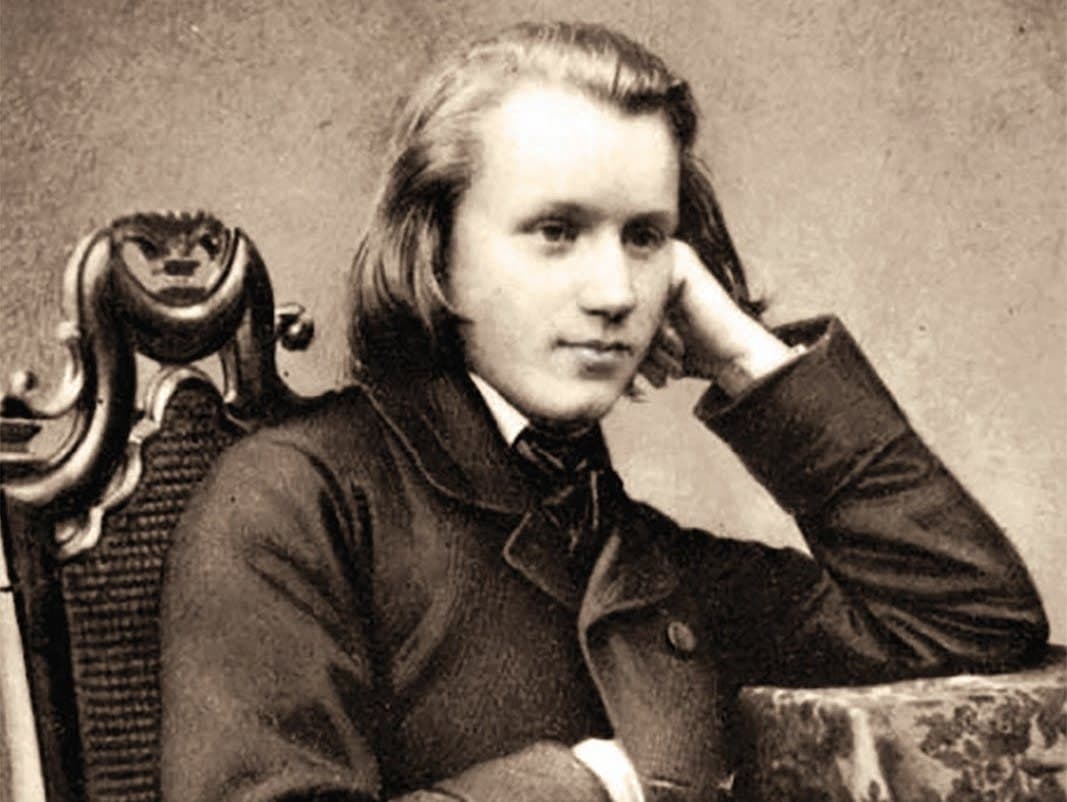

Brahms: Piano Sonata No. 1

Between 1852 and 1853, the 20-year-old Johannes Brahms wrote what became his official Piano Sonata No. 1 in his hometown of Hamburg, Germany.

Thing is, it wasn’t his first piano sonata. He had written another one first. However, like Beethoven, he thought that this work was stronger, and chose to bestow upon it the more monumental Op. 1 designation.

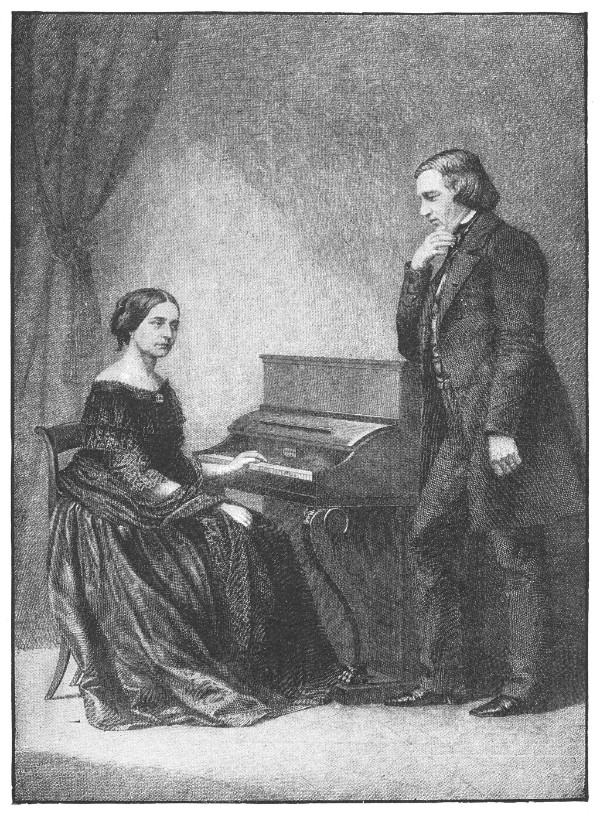

Johannes Brahms, 1853

From the very first measures, it is clear that this sonata is symphonic in scope. The chords are so full, it seems like this is a transcription for piano of a work for orchestra.

Some have even likened the opening movement to Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata.

These thick textures and the general seriousness of this sonata speak to the decades-long struggle of Brahms’s youth, and the desire he had to fulfill his potential by completing a symphony. That particular creative journey would take over twenty years, not bearing fruit until his Op. 68!

Chopin: Rondo in C minor

Chopin published his Rondo in C-minor for solo piano in 1825. Remarkably, he was only fifteen years old at the time.

Even as a teenager, he was clearly aware of the social and cultural import of dedications. His charming rondo was dedicated to the wife of the headmaster of the Warsaw Lyceum where Chopin was a student, and where his father was a French language professor.

Frédéric Chopin

Chopin gave the Rondo’s public premiere in 1825 at a concert at the Warsaw Conservatory.

Interestingly, in 1832, composer Robert Schumann wrote to his piano teacher and future father-in-law, Friedrich Wieck, about this work. He seemed to have mixed opinions about it:

Chopin’s first work (I believe firmly that it is his 10th) is in my hands: a lady would say that it was very pretty, very piquant, almost Moschelesque… But I humbly venture to assert that there are between this composition and Op. 2 two years and twenty works.

Mendelssohn: Piano Quartet No. 1

Felix Mendelssohn was one of the most extraordinary musical prodigies in music history.

Unlike most of his fellow composers, Mendelssohn was just a teenager when he wrote some of his greatest masterpieces, including the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture for orchestra and the Octet for double string quartet.

Felix Mendelssohn

This particular piano quartet – scored for piano, violin, viola, and cello – was finished in October 1822, when Mendelssohn was just thirteen years old. (He’d turn fourteen the following February.)

This piano quartet was published with two others as his Op. 1 in 1823.

Mendelssohn dedicated the work to Antoni Radziwiłł, aristocrat, arts patron, and friend to Beethoven, Chopin, and Szymanowska.

Mozart: Violin Sonatas No. 18, No. 19, and No. 20

Speaking of musical prodigies, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is right up there with Mendelssohn in terms of sheer precociousness.

Mozart began composing in 1761, when he was five years old. However, his Op. 1 wasn’t published until 1778, when he was 22.

His Op. 1 collection consists of three violin sonatas, nowadays known as the Violin Sonatas No. 18, 19, and 20.

Mozart in Italy

He composed them while traveling in Mannheim, Germany, after resigning from his position as court musician in his hometown of Salzburg.

At the time, one of the world’s greatest orchestras was located in Mannheim, belonging to the court of the Elector Palatine.

So it’s no mystery why Mozart dedicated the first three sonatas in his Op. 1 to Countess Palatine Elisabeth Auguste. Because of that dedication, these three sonatas are sometimes known as the Palatine sonatas.

Each one is relatively brief and only two movements long. It’s a modest and inauspicious start to one of the most impressive lists of opus numbers ever composed.

Prokofiev: Piano Sonata No. 1

Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata No. 1 was written in 1909, when the composer was eighteen years old. However, it was based on material he had written while a rebellious fifteen-year-old student at the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

Sergei Prokofiev in 1918 © Wikipedia

This is a slender Op. 1: it only consists of this sonata, and this sonata is just eight minutes long.

One can hear the influences of the late Romantic era, but the work’s relentless rhythmic drive hints at the thoroughly modern, twentieth-century composer that Prokofiev would later become.

Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 1

Rachmaninoff is the only composer on this list whose opus 1 was a concerto.

What we know today as his first piano concerto was written in 1891 when he was in his late teens.

Interestingly, chronologically speaking, this was not his first piano concerto; it was his second. He had written another one at an even earlier age, but didn’t like it enough to present it as his Op. 1.

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Another thing that makes this first opus special is that Rachmaninoff returned later in life to heavily revise it. This reimagining of his youthful first concerto happened in 1917, when he was 44.

Despite Rachmaninoff’s hard work, his next two piano concertos would far eclipse his first in popularity. Even in his own day, he recognised the audience’s tastes, complaining to a friend:

I have rewritten my First Concerto; it is really good now. All the youthful freshness is there, and yet it plays itself so much more easily. And nobody pays any attention. When I tell them in America that I will play the First Concerto, they do not protest, but I can see by their faces that they would prefer the Second or Third.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter