After Brahms wrote his two brilliant string sextets, Dvořák, Erwin Schulhoff, Schoenberg, Tchaikovsky, Reger, Rimsky-Korsakov, Franck, Korngold, Martinů, and others followed suit. I’d like to feature two Czech composers’ sextets.

After Brahms wrote his two brilliant string sextets, Dvořák, Erwin Schulhoff, Schoenberg, Tchaikovsky, Reger, Rimsky-Korsakov, Franck, Korngold, Martinů, and others followed suit. I’d like to feature two Czech composers’ sextets.

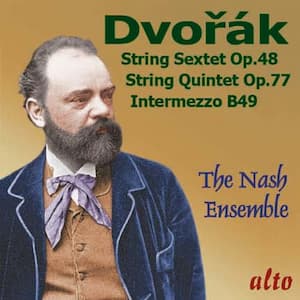

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1903) the first of 14 children, showed exceptional talent as a youngster, but his early years were plagued by poverty. He could hardly afford concert tickets or a piano. As luck would have it he became the recipient of a multi-year Austrian State Scholarship in 1874 when Brahms served on the program’s panel. He heartily endorsed the talented younger composer. Brahms also introduced Dvořák to the Berlin publisher Simrock who immediately published Dvořák’s Moravian Duets and his Slavonic Dances.

In 1878 Dvořák composed his String Sextet in A Major Op. 48 in just two weeks. Joseph Joachim (the legendary violinist who premiered Brahms first sextet) was so impressed with Dvořák’s sextet, he arranged to perform the piece for a private soirée at his home in Berlin, the composer among the invited guests. It was the first time Dvořák’s music was heard outside of his country. Joachim subsequently took the piece on tour throughout Europe, to London, and to New York.

Antonín Dvořák

This work, composed during Dvořák’s so-called “Slavic period”, features Bohemian folk elements, and like the Brahms sextets, has four movements. The two middle movements are quintessentially Czech in flavor. The Dumka, a Czech elegy, marked Poco allegretto is a charming movement. As is typical, it features several sections that contrast with the melancholy mood of the Dumka. The opening lilting 2/4 section, is followed by a slow dance and slips subtly into a 3/4 meter until the lilting section returns. The Furiant Presto third movement maintains this folk-dance quality. The captivating theme is introduced by the violas and Dvořák here pairs the three instrumental duos, the violins often playing together in octaves.

The Finale: tema con variazioni requires tremendous and subtle expertise from the players. The theme is first introduced by the soulful voice of the viola gently and sparsely accompanied by the other players. The second variation continues the melody in the inner strings but with a gentle triplet figure in the first violin. The disarming nostalgia is interrupted when the group explodes scherzando into fast spiccato punctuated by accented offbeats. This requires exceptional control from the musicians. With a quick breath, slower, the cello enters with the tranquil theme against a backdrop of hushed held notes in the upper strings. Two variations follow—the first a duple meter accompanied by triplet repeated notes in the second cello; the second a soaring violin melody accompanied by flowing 16th notes in the middle strings. It is masterfully crafted. The final variation requires utter exuberance and daring from the players. Gradually accelerating from the vigorous dotted rhythm, it moves through duples, then triplets, then sixteenth notes, faster and faster until the breathless finish. What a showpiece for the performers.

Antonín Dvořák: String Sextet in A Major, Op. 48, B. 80 (Jerusalem Quartet; Veronika Hagen, viola; Gary Hoffman, cello)

Erwin Schulhoff

Composer and pianist Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) was born in Prague when the city was a center for culture within the Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire. He came from a family that boasted several musicians, who were proud of their German as well as Slavic side, but his Jewish heritage would be his undoing. Upon the encouragement of Dvořák, Schulhoff studied in Vienna, Leipzig, and then Cologne. Once he returned to Prague, when World War I ensued, he was drafted into the Austrian army. Schulhoff, wounded twice, never forgot the horrors he witnessed. He settled in Dresden after the war and began to establish himself internationally. As a soloist, he performed in major centers such as Paris and London, and he performed many of his own works including as one of the soloists in his Double Concerto with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam.

Erwin Schulhoff’s Fünf Pittoresken Jazz pieces with the movement of silence notated

One of the first composers to employ jazz in his classical compositions, his Fünf Pittoresken, for solo piano is an example of his humor. Written in 1919 with titles ragtime and foxtrot, the third piece, In Futurum is performed entirely in silence although notated with rests throughout the movement. (It predates John Cage’s 4’33” by more than three decades—a controversial piece, of “the absence of intended sounds” that reflects Cage’s ideology that any auditory experience may represent music). Schulhoff wrote a great deal of chamber music, concertos, sonatas, a fabulous duo for violin and cello, 5 études de jazz, and several symphonies. Once the Nazis came to power in the 1930s his music was banned and declared ‘degenerate’ not only due to Schulhoff ‘s Jewish heritage, but also because of the music’s modern and jazz idioms.

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Études de jazz – No. 2. Blues (for Paul Whiteman) (Eldar Nebolsin, piano)

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Études de jazz – No. 4. Tango (for Eduard Künnecke) (Eldar Nebolsin, piano)

Unlike his other works which include jazz and the rhythmic stamp of Czech dance music,

Schulhoff’s Sextet, a powerful masterpiece, dramatizes the dread and torment with which he lived after WWI. The work took four years to complete. The composer Paul Hindemith participated in the premier of the work in 1924 but the sextet was not performed again during Schulhoff’s lifetime, and although a score was printed in 1978, the individual parts were not. Gidon Kremer spearheaded the release of the individual parts and performances of the piece in the 1980s.

Erwin Schulhoff: Sextet

Woodcut of Schulhoff by Conrad Felixmuller

The sextet opens with ferocity, Allegro “risoluto” as if each musician is clambering to dominate the others with fierce dotted rhythms. The second movement Tranquillo Andante is haunting. A muted repetitive pattern soft and mesmerizing played by the violins, is the accompaniment to a dark melody in the lower strings. Briefly, a passionate section interrupts but soon the lilting repeated pattern returns this time in the lower strings superimposed upon a violin melody played non-vibrato. Time seems to stand still when one lone cello plays virtually a-rhythmically. The movement ends with shimmering tremolando in the strings con sordino (with mutes) leaving us with a murmuring question mark. To play inaudibly and motionless requires tremendous control from the musicians and it is breathtaking.

In the forceful and intense Burlesca Allegro molto con spirito, Schulhoff maintains the melancholy mood. The finale, an Adagio, begins again with the lowest strings in their lowest positions. One can feel the composer’s anguish, his soul-searching, and slowly we are pulled into his bleak world. The solo cello returns seemingly without meter and when the violins enter they play a muted nebulous pattern. The movement ends sorrowfully in an eerie trance fading out pianissimo. For me, the sextet has a message that arouses awe-inspiring revelations in the musicians and the audience.

We know today of other Czech composers Pavel Haas, Gideon Klein, Viktor Ullmann and Hans Krása, who were put to death in the concentration camp just north of Prague, Terezín (Theresienstadt). Schulhoff was deported to Wülzburg concentration camp in Bavaria where he died of tuberculosis in August 1942.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Cesar Franck did not compose a string sextet (alas!)